by Andrea Scrima

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

There are now thirty-eight years of absence in my blood, of not having lived in New York, and apart from the fact that all the time that has passed and everything that has come since have gone into making the person writing these words, there is, on some other level of existence, a version of me that stayed behind, that longed to leave and yet never did, and I feel the loss of the time I didn’t spend in the city of my parents and grandparents and great-grandparents, mixed with a sense of betrayal, and all at once everything seems like some kind of terrible misunderstanding, and I have no idea why I stayed away so long. For some people, whether they stay or go, the pain of lost or unrealized identity follows them around like a faithful animal. My departure, of course, was entirely voluntary; the pang I still occasionally feel no more than hints at the plight of the political exile and refugee, in other words, people who have no other choice but to leave.

*

In late 2018, German researchers found that one in three people who had fled the war and political persecution in Syria suffered from some form of mental illness. The symptoms often appeared after a time delay; many of these people had been so consumed with the exigencies of their asylum applications and the bureaucratic procedures these entailed, with language difficulties and coping with a foreign environment, that the signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, clinical depression, or chronic anxiety only began to surface later. For those afflicted, it was a cruel irony that just as their external circumstances began to improve, just as they’d succeeded in finding a home and job and a future once again seemed possible, the past caught up with them.

Refugees who had been victims of torture or had witnessed their parents or children being killed were often already in a state of disassociation upon arrival. Although virtually all of them had endured a long and grueling odyssey and had lost friends or family along the way, mental illness rarely factored into the decision to grant or deny political asylum, even in cases where suicide attempts had been documented. Applicants were not routinely screened, and symptoms of severe trauma were frequently misdiagnosed as schizophrenia or general psychosis.

When the Coronavirus appeared and European countries went into lockdown, civilians fleeing the violence in northern Syria and elsewhere more or less vanished from the news. Suddenly, the plight of individuals trapped in overcrowded camps was no longer considered a humanitarian crisis, but a hotbed for disease. When almost half the residents of a detention center in Baden-Wurttemberg tested positive for Covid-19, authorities were less concerned with protecting the lives of the uninfected half than in preventing anyone from entering or leaving the premises. This othering of the virus was nothing new; foreigners have always been equated with disease and contagion. Now, however, in spite of the danger that the virus could spread unchecked among a refugee population already worn down and vulnerable to disease, aid groups were prevented from monitoring the situation or providing humanitarian assistance.

In the Moria camp on the Greek island of Lesbos, conditions had reached disastrous proportions. The lack of basic hygiene, including access to showers, toilets, and facilities to launder clothing, coupled with inadequate shelter and an environment of escalating violence, took a high toll on mental health. Feelings of impotence and desperation, fury, recurrent terrors, and, among the more severely traumatized, hallucinations and psychotic outbursts were the unsurprising result of being incarcerated in a squalid facility that offered those trapped little hope of gaining access to education, work, or healthcare, or the prospect of one day resuming their lives under more humane and dignified circumstances, or protecting their children—many of whom retreated into the extreme withdrawal of the so-called resignation syndrome, engaged in self-harm, or attempted suicide.

Where refugees did eventually secure residency status or asylum, most of those referred to psychologists and psychiatrists politely refused or abandoned the therapy prescribed them. This was due to many factors, including fundamentally different concepts of the cause and nature of mental and emotional suffering. Susceptibility and symptoms vary widely across cultures, religion frames the perception of disease and the meaning it holds in a person’s life, and therapists are rarely able to shed their preconceptions and fully identify with the patient’s predicament, to address or acknowledge geopolitical injustice, or to understand the awful way in which immigration is often both salvation and traumatization in one.

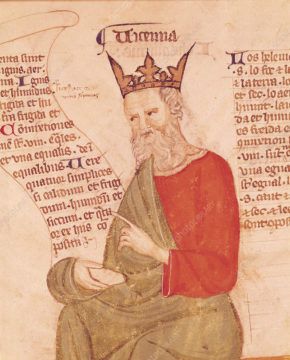

In one of history’s strange ironies, even if many refugees regard therapy as an unnatural Western invention, the earliest approaches to psychological treatment are to be found in the Middle East. The medieval Persian polymath Ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna and considered to be the father of early modern medicine, proposed that the site of disease lay in the physiological link between mind and body. He once restored health to a young man suffering from a mysterious psychosomatic illness by ordering his parents to allow him to marry the woman he was hopelessly in love with. Before him, al-Razi had founded the first psychiatric facility in Baghdad and was one of the earliest thinkers to reject the mind-body dichotomy propagated by Socrates and Aristotle. Al-Razi treated his patients with a combination of diet, herbs, aromas, music, baths, and what we refer to today as occupational and talk therapy, and supplied them with a small sum of money upon leaving the hospital to help them get back on their feet. Nonetheless, the belief persisted throughout the Muslim world that it was the Jinn who were largely responsible for misfortune, particularly mental illness—just as medieval Europeans sought the source of disease in demons and evil spirits, a belief that prevailed among peasants for centuries and made its way across the Atlantic, where it took concerted campaigns on the part of medical professionals, school nurses, and public health authorities to overcome the deep suspicion immigrant communities harbored toward modern medical practices, including vaccination.

*

A few years ago, I submitted the documents required to apply for German citizenship. I arrived at Rathaus Schmargendorf fifteen minutes early, which gave my thoughts time to drift as I waited in the corridor. It’s a familiar experience by now—benches and corridors—so familiar that my body recognizes it, instantly understands what it’s expected to do. I become docile, resigned. It’s ingrained in me, one bench merges with another, and as I’m drawn into a tunnel of endlessly extending benches comprised of all the corridors I’ve waited in over the years, all the visas, work permits, visa extensions, work permit extensions I’ve applied for merge in a blur. Although I’m aware of my comparative privilege, I am nonetheless a supplicant: I ask for things I, a non-citizen, do not have a natural right to. The restrictions that apply to me as a foreigner carry an unspoken implication: I am a potential outlaw, at the very least a future burden to the system. Three-quarters of an hour later, as I boarded the 249 bus without paying the proper fare, it seemed that the suspicion leveled at me had only served to encourage my criminal nature, and that it would, in the minds of some, therefore seem justified.

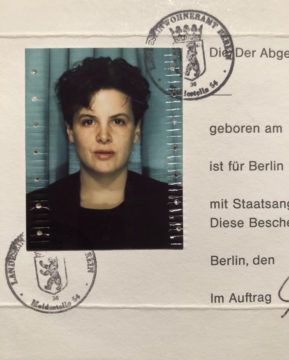

Scared away by my first appointment with the Einbürgerungsamt and the list of dozens of documents the clerk had vigorously highlighted in yellow, to which, replacing the cap on his Day-Glo marker and switching to a ballpoint pen, he’d added a row of exclamation points, it took me nearly two years to give the citizenship application another try. During this time, the clerk to whom I was originally assigned unexpectedly passed away. The new clerk was young, friendly, informative—and evidently not determined to torpedo my application with an impossible list of bureaucratic demands. Herr H. had insisted I take a language test, and barked at me when I offered that books I’d translated could be found in the online data base of the German National Library, yet here was Frau I., informing me that a test wouldn’t be necessary: she could, after all, clearly hear that I was fluent; it was a matter of common sense. But before I discovered the benevolent goodness of Frau I., before I understood the degree to which the mood, disposition, political leanings, prejudices, and general choleric or sanguine nature of the person deciding my case could actually factor into that decision, it was the hallway and the bench I was seated on that absorbed my attention. Mine was next to the door to Room No. 10; further down the hallway, a woman was seated on a bench next to Room No. 12, and I was unable to shake the impression that Rooms 10 and 12 were not merely separated by a simple bureaucratic distinction, for instance the first letter of the applicant’s surname, but that there was some other, unbridgeable gulf between them that made the woman waiting in silence outside Room No. 12 avoid my gaze, made her seem farther away than the four or five meters’ distance between us, as though she inhabited another dimension. I felt sure that regardless of the difficulties I was having with the seemingly insurmountable hurdles in place between me and German citizenship, my sense of estrangement and alienation was in all likelihood harmless compared to whatever she was going through.

As I sat on the bench outside Room No. 10, I thought about all the information that had accrued in my 34 years of living in Berlin: the files at the Ausländerpolizei and my strange parallel existence within them; the problems I’d encountered after I’d exmatriculated from the art academy. No longer a student, I had to sort out my visa status on my own; I’d already received an official work permit and had been paying taxes on my freelance income for several years, and so when I set off for the Alien Registration Office, it was with the intention of applying for an unlimited residence permit: all my papers were in order, or so I thought, and I’d been living in the country and paying into the social security system longer than the required six years. I handed everything over to the clerk; he leafed through the documents and informed me that I would hear back in due time.

As I sat on the bench outside Room No. 10, I thought about all the information that had accrued in my 34 years of living in Berlin: the files at the Ausländerpolizei and my strange parallel existence within them; the problems I’d encountered after I’d exmatriculated from the art academy. No longer a student, I had to sort out my visa status on my own; I’d already received an official work permit and had been paying taxes on my freelance income for several years, and so when I set off for the Alien Registration Office, it was with the intention of applying for an unlimited residence permit: all my papers were in order, or so I thought, and I’d been living in the country and paying into the social security system longer than the required six years. I handed everything over to the clerk; he leafed through the documents and informed me that I would hear back in due time.

One week later, I received a letter from the Kriminalpolizei. I was in violation of the Aliens Act: I had been engaged in gainful employment without the requisite permission. It turned out that the work permit I’d been granted applied exclusively to employee status; freelance work required a different type of permit. All, in fact, I would have needed to request was for the clerk to cross out the prohibition stamped in my passport, a measure he could easily have performed then and there. Instead, he took my documents without even hinting that I was implicating myself in a crime. After that first appointment at the Einbürgerungsamt, a part of me wondered if, through some very strange twist of fate, it had been none other than Herr H. in the early days of his career who’d allowed me to walk into a trap and then turned me over to the Police Criminal Investigation Department, and while it’s possible that the written request to initiate the investigation has survived somewhere in my records, and likely that it carried the clerk’s signature or initials, it seems all but certain that I will never know for sure.

*

What I remember from my first trip to Berlin nearly forty years ago: the overnight ride through the transit route of the GDR; the loud knocking on the sleeper cabin door when East German immigration officials boarded the train to check passports. The military uniforms and expressionless faces and curt, clipped movements, the political theater and humorless drama of it all. I’d won an academic stipend that kept me alive and fed for two years, but every time I was forced to mention the awarding institution, which was named after the Berlin Air Lift, it met with a smirk. I became embarrassed to say it; it wasn’t as prestigious as a Fulbright, and it seemed to provoke a kind of disdain, a reaction, perhaps, to the gratitude people believed was expected of them for American humanitarian aid during the Soviet blockade that had nearly driven the city’s inhabitants to starvation. Sentiment towards Americans tended to come in two extremes: love and a sometimes servile admiration, or a deep, resentful antagonism mixed with arrogance. It was the worst part about leaving the U.S.: outside its borders, regardless of my political beliefs, I symbolized the country, stood for it. There was no escaping it, and I spent my first five years in West Berlin avoiding Germans and hanging out with other foreigners like myself. Because for us, Germany was the truly uncanny place to be: it hadn’t yet been forty years since the Holocaust, and the German horrors haunted our minds and hearts and the darkest corners of our souls.

I’ve been living in Berlin for well over half my life now; I can’t remember what German once sounded like to my non-native ears, when it was still a foreign language. I make my living translating, and I’m accustomed to switching back and forth between languages. I’ve witnessed two generations of people my age and younger struggling to come to terms with the country’s past, and saw the stranglehold that past still held gradually wane; I’ve grown to admire German distrust of nationalism, flags, and political fervor of any kind. And given the instability of the world, I am more than comfortable having dual citizenship. But vestiges of resistance remain, and, like an adolescent, I find myself breaking minor rules whenever I can: I cross at the red, ride my bike on the sidewalk, and complain bitterly about the traffic laws, which are numerous, complicated, and counterintuitive.

I’ve never exactly worked out why I came to Berlin, or why I stayed; I didn’t entirely understand the strange forces of a family’s past, or that Germany was just as much a part of my history as Italy, albeit a less emotionally accessible one. I’d left New York while Ronald Reagan was president; the Movement Conservatives had finally prevailed with their anti-New Deal ideology and their narrative of the lone hero’s rugged individualism in the face of an empire attempting to destroy him. This, of course, fed skillfully into Hollywood interpretations of the national mythology, and when Reagan adopted “Star Wars” as the nickname for his spectacular, unfeasible nuclear missile defense program, it was the first time that the entertainment industry had entered the political discourse in such a transparent manner. It also introduced the biblical binary of good and evil to appeal to an uneducated constituency to vote against their better interests, and then capitalized on this for its own purposes.

Throughout the twenty-eight years of West Berlin’s sequestered existence as an exclave in the East, the counterculture that formed here effectively subverted the Federal Republic’s paving over of the past; the city was a magnet for artists, dancers, musicians, filmmakers, and writers, and a center of political resistance. Long before the post-Reunification influx of people looking for an alternative to the overpriced cities of the West inevitably gentrified it, before the rents skyrocketed, before an English-language literary community formed here and provided a context to my writing existence that I hadn’t realized I needed, Berlin was a very different animal. The images that come to mind are watchtowers and soldiers, barbed wire, and apartment buildings overlooking the Wall; merchants in unheated cellars selling coal and potatoes. Flea markets and junk shops were full of old postcards bearing stamps with Hitler’s profile, identity cards for the Hitler Youth and League of German Girls, WWII food stamp cards, old linen and dishes, photographs of men in Wehrmacht uniforms. The war generation was still alive: widows walking their dachshunds along cobbled sidewalks and scolding anyone who crossed their path; antagonistic, xenophobic neighbors in their sixties or seventies or eighties, in all likelihood unrepentant Nazis, or so we imagined.

The year I arrived in West Berlin, I attended an election party at Amerika Haus. Watching the crowds on a large TV screen cheering Reagan’s reelection, I suddenly understood that I would not be going back any time soon. The cultural shock stunned me; I was asked to explain how a second-rate Hollywood actor could occupy the country’s highest office, and I’ve been trying to explain it ever since—because the irrational nature of U.S. politics did not, of course, begin with the past administration. Some months later, Amerika Haus put up a show of photographs by Robert Frank; it was the first time his work was exhibited in Germany. The black-and-white prints from The Americans penetrated to the country’s molten core in a way only the work of the foreign-born is able to do—Frank was Swiss—, and the image from the invitation card remained pinned to my wall for years. Two windows in a brick tenement: in the left-hand one, cast in shadow by a half-drawn shade, is a stout older woman wearing a summer dress; rigged outside her window, fluttering to the right and concealing the face of a woman standing in the adjacent window, is a gigantic American flag. The woman in the second window is wearing a coat with three large buttons. Only her hands are visible: she’s holding one to her face, perhaps her mouth, while the other shows the glint of a ring. Her view of the parade taking place in the street below—in other words, her view of the reality taking place before her very eyes—is blocked, at least for the time being: all she can see is the enormous flag in front of her.

*

When I think of the way the faces of people living in diaspora suddenly light up when they’re speaking their native language, when I think of how their demeanor becomes livelier and funnier as they shake off the monotonous sounds of the acquired tongue and slip into the rhythms and melodies of their childhood, I imagine them striding out onto a dancefloor, confident in the body memory of a dance they mastered long ago. All at once, we realize with a pang that a large part of their person lies dormant, buried beneath the new life and new language, and that this is the part of themselves they are unable to pass on to their children, that will die with them, die off with them: that they never taught us to dance.

It’s more than a disruption in the transmission of knowledge and cultural information; the ways in which a person’s relationship to inner and outer reality is imbedded in language are mysterious and unpredictable and tap into the very core of identity, sense of self, and presence in space and time. When parents, faced with insuperable cultural indifference or political repression, fail to teach their children their native language, it’s not merely the language itself that’s lost: entire layers of memory and experience can no longer be passed on in their original, authentic form. It’s for this reason that psychologists often discourage patients from undergoing psychotherapy in a language acquired later than childhood, regardless of their level of fluency: the likelihood of accessing deeply imbedded memories is slim. For grown children unable to speak the language of the country or culture their parents come from, there is no going back in time to reclaim the birthright, because the emotional experience of a native tongue is tied to childhood, when it was absorbed in all its newness and freshness and the discovery of language was immediate and urgent and everything was seen, perceived, and understood for the first time. And while the sounds and melodies of the lost language will feel familiar and even intimate to these lost children, they are trapped forever on the outside: they cease to belong to a deeper past; their rootedness remains shallow. In my case, I learned Italian as a schoolgirl, but it took far more effort to learn the other, lost language of my mother’s family. And although my German is excellent, I never had the opportunity to hear my great-grandparents speak in their native tongue, or they me. Whatever stories could only be told in the cadences of Swabian or Kölsch, whatever sense of identity there might have been to impart, I will never know.

A good friend of mine was born in the Soviet Union; a few years later her family moved to Kyiv, and when she was ten, they moved again, this time to Germany. She started school with no understanding of German, learned the language quickly, and assiduously erased all traces of her native tongue as she navigated the rough neighborhood they lived in, dealt with everyday xenophobia, and hid her identity as best as she could to escape the discrimination leveled at every person with a “migrant background.” Later, after studying philosophy, she became a writer, and she made sure that none of the press material the publisher sent out into the world contained any information whatsoever about her origins. It was her secret, and she guarded it meticulously. Russia and Russian had become an emotional problem: she was unable to speak it, even when she tried; it lay tied up in knots, entangled in a complicated mess of feeling and affect, a stress trigger buried beneath the trauma of immigration. It wasn’t until Russia invaded Ukraine and she volunteered to help as hundreds of thousands of refugees began pouring into the city of Berlin that her relationship to her mother tongue was gradually restored. She was no longer the outcast; now, her ability to speak both Ukrainian and Russian fluently was essential and badly needed. And it took on new meaning: for thousands of frightened people disembarking the train at Berlin Hauptbahnhof throughout March, April, and after, she became an anchor in a sea of confusion, a kind of miracle: a locking of eyes, the first friendly words, tense faces suddenly relaxing in tearful relief. She gave them hot tea and a shoulder to cry on, no small feat given her small stature; she listened to their stories, dispensed food, diapers, and vital information, made people laugh in spite of themselves, and tried to facilitate accommodations in the absence of any official aid and under the constant danger of human traffickers infiltrating the support networks that had sprung up spontaneously in the first days and weeks of the war.

In terms of America, when I think of entire generations of children never having experienced the power of language to conjure multi-generational memory—never having experienced their own parents in their most authentic form—it explains something about the national psyche, this country of immigrants for whom the imperative to become American was paramount and never questioned. How did it affect my grandfather Luigi’s relationship to his children, I wonder, that of his seven sons and two daughters, only the first- and second-born learned some Italian, while none of them understood Arbërisht, the medieval Albanian dialect of his native village? When the language with the sole power to conjure generational memory was incomprehensible to his offspring? Of his two native tongues, Luigi could share neither with his children, and so he had no other choice but to communicate in a language he only began learning when he was nearly 24. He never attained a strong command of English and congregated mainly with his fellow villagers from Greci, many of whom moved to the same neighborhood in the South Bronx. This would be the role he would take on for his children—the immigrant inept in the ways of the New World—and it would forever chip away at his authority.

My parents, the children of foreigners, never learned their families’ native languages; in a country at war with their parents’ homelands, they were discouraged from doing so. This lack of curiosity on the part of the American-born children, this dictate to blend in and become American at all costs—even while carrying the outward trappings of ethnic identification to its nostalgic extreme—is the paradox, the obvious contradiction that defines us. Many years later, as an American in Europe, I never felt forced to assimilate in the way other immigrants are expected to do; when I had my son, I spoke English with him and later enrolled him in a bilingual school, which is far more commonplace here now than it was fifteen or twenty years ago. He does a pretty good imitation of an Italian American gangster; I wonder if this phantom American identity has stood in the way of him feeling fully German, and what it will seem like to him later on—and if he’ll gravitate back to the “homeland,” whatever that might come to mean for him—just as his mother once did.

(to be continued)