by Mary Hrovat

I had my first experience with Daylight Saving Time when I was 9 or 10 years old and living in Phoenix. Most of the country was on DST, but Arizona wasn’t. I knew DST as a mysterious thing that people in other places did with their clocks that made the times for television shows in Phoenix suddenly jump by one hour twice a year. In a way, that wasn’t a bad introduction to the concept. During DST, your body continues to follow its own time, as we in Phoenix followed ours. Your body follows solar time, and it can’t easily follow the clock when it suddenly jumps forward.

I had my first experience with Daylight Saving Time when I was 9 or 10 years old and living in Phoenix. Most of the country was on DST, but Arizona wasn’t. I knew DST as a mysterious thing that people in other places did with their clocks that made the times for television shows in Phoenix suddenly jump by one hour twice a year. In a way, that wasn’t a bad introduction to the concept. During DST, your body continues to follow its own time, as we in Phoenix followed ours. Your body follows solar time, and it can’t easily follow the clock when it suddenly jumps forward.

When I moved to Indiana as a young adult, I was relieved that my new home, like Arizona, didn’t observe DST. The history of time zones in Indiana is complex. When I moved here in 1980, most of Indiana was on Eastern time. Because the state is on the western edge of Eastern time (and arguably ought to be on Central time), DST makes less sense for Indiana. We already have relatively late sunrises and late sunsets. Eastern time is one zone east of where we should probably be. We don’t need DST to effectively move us one time zone even further east.

Before standard time zones existed, all time was based on local solar noon. Indianapolis is closer to the center of the Central time zone than to the center of the Eastern time zone, as currently defined, and until 1960, the entire state was on Central time. However, for various reasons, the state crept into the Eastern time zone, first just half of it and then most of the rest. The exception is 12 counties in the northwestern and southwestern corners, which chose to be on the same time as nearby regions on Central time. Read more »

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

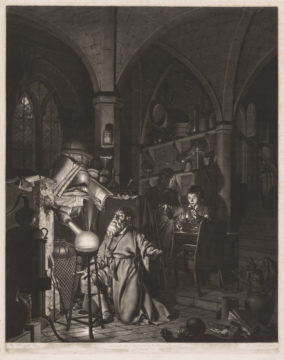

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.

One of the easy metaphors, easy because it just feels true, is that life is like a river in its flowing from then to whenever. We are both a leaf floating on it, and the river itself. Boat maybe. Raft more likely. But those who know such things say there is a river beneath the river, the hyporheic flow. “This is the water that moves under the stream, in cobble beds and old sandbars. It edges up the toe slope to the forest, a wide unseen river that flows beneath the eddies and the splash. A deep invisible river, known to its roots and rocks, the water and the land intimate beyond our knowing. It is the hyporheic flow I’m listening for.” The person speaking is Robin

One of the easy metaphors, easy because it just feels true, is that life is like a river in its flowing from then to whenever. We are both a leaf floating on it, and the river itself. Boat maybe. Raft more likely. But those who know such things say there is a river beneath the river, the hyporheic flow. “This is the water that moves under the stream, in cobble beds and old sandbars. It edges up the toe slope to the forest, a wide unseen river that flows beneath the eddies and the splash. A deep invisible river, known to its roots and rocks, the water and the land intimate beyond our knowing. It is the hyporheic flow I’m listening for.” The person speaking is Robin There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church:

There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church: