by Mike Bendzela

“What genre do you play in, Mike?”

“Old time.”

“That’s rather vague, isn’t it?”

[An actual conversation.]

Old time music (some write “old-time” or “oldtime”) is where my interests in rural American folk history, cultural evolution, and language-play come together to form a most satisfying way to lay waste to time. Yes, old time is a thing.

At the end of the last century, at the age of 39 and seemingly without conscious volition, I rented a violin. I thought I wanted to be a “bluegrass” player. I was so naive I had to ask the clerk at the music rental store, Is the fiddle the same as the violin?

The answer is, Yes, but no. Turns out, I wasn’t actually interested in playing no stinkin’ bluegrass violin. This requires some explanation.

The radio station at the local university where I work used to have a program called “Lost Highway,” which featured old country music: folk, old time, honky-tonk, all of which I thought of as “bluegrass.” Some of this bluegrass I liked; some of it I found extremely irritating. I had yet to learn the fine distinctions among genres. But some of this music was enchanting, haunting, primeval.

Then, in 2002, I swung by The Appalachian String Band Festival (“Clifftop”) at Camp Washington-Carver, in the West Virginia mountains, on the way back to Maine after a family reunion with some relatives in Kentucky. I tend toward social avoidance and usually don’t go to such places, but Clifftop turned out to be a road-to-Damascus moment for me: At last, I had found my genre—and, presumably, my people. When I expressed my amazement over lunch to an Asian-America fiddler and software developer sitting at a picnic table with me, he enthused, “Start listening to Bruce Greene!” I was on my way to learning a new language. The timing was perfect: my ambitions of being a fiction writer had quietly crashed, and I was seeking something redemptive to do. Finding old time was like being handed a loaf of crusty bread after a ten-year diet of wet sawdust.

As I was still a beginner player, I did not participate in any of the jam sessions but spent the day walking from tent to tent, from camper to camper, watching and listening to fiddlers, banjo players, mandolin players, guitarists and bassists sawing and plucking their way through myriad tunes that go back to pre-Civil War America. Some people joined in with spoons or bones, even a washtub bass. Someone danced on a board. At Clifftop the distinction between “bluegrass” and “old time” became clear, stark, and irrefutable. I realized we have the phenomenon called bluegrass because we had (and still have) old time, the same way we have passerine songbirds because we once had theropod dinosaurs.

I learned that whereas bluegrass is performer oriented, old time is tunes oriented. Bluegrass highlights hotshot players with their “breaks” and “licks” and original songs; old time highlights the ensemble playing traditional tunes. It was becoming apparent to me that bluegrass–a distinctly modern and sophisticated form of playing–lay beyond my abilities and would forever remain so. Bluegrass is slick, old time rough-hewn. A bluegrass ensemble is a string band on amphetamines. Bluegrass is not the stuff of hobbyists like me. (Not that all old time players are hobbyists: many are spectacular musicians. Check out, for instance, Walt Koken & Clare Milliner, Rayna Gellert, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, Bruce Molsky & Allison de Groot.)

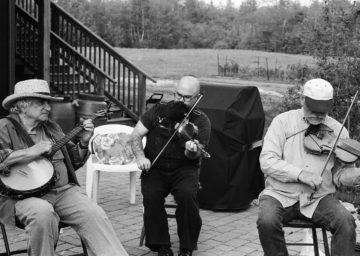

In casual old time jams, the fiddler is the leader and calls the tunes, but he or she does not solo or improvise or otherwise show off. Old time fiddlers mostly dispense with vibrato, long-bowing, soloing and improvisation. The players sit in a circle–sometimes knee-to-knee–and play the melody, over and over, until the whole group enters a sort of trance-like state of communal bliss. Once they’ve had enough of it, the lead fiddler raises a foot to signal it’s time to end the tune.

Like many of the players in the old time group I’m part of, I have no background in music. (Thus, the self-deprecating humor of many old time players.) If one has a decent ear, an intact memory, and the time and will to practice (i. e. no life), one can play with others in a few years. It helps if one is mad for the music.

I was lucky enough to find a reputable folk fiddler nearby, the legendary Ben Guillemette (1926-2021), who taught me technique for a couple of years in his workshop in Sanford, Maine. He also sold me two of his hand-made fiddles for a reasonable price. We parted ways after I discovered I’d rather play Appalachian old time than the French-Canadian/Quebecois fiddling that Ben was famous for. (Too notey and upbeat for my tastes. Old time tends to be darker and funkier.)

I like to say that we old time players play in all five keys: A, C, D, G, and “modal.” This is an old time colloquialism; modal is basically A minor, or something like that. A professional musician once said to me, “Well, every tune is in some mode,” but I had no idea what that meant. She explained, “‘Cold Frosty Morning’ is in A Dorian mode.” Whatever! It’s modal! I was becoming acutely aware of my own ignorance in music. When I look at the Wikipedia entry on music modes, I feel like screaming and running from the room. If nothing else, fiddling around with old time has taught me an immense respect for the complexities of music. Bluegrass adds E, Bb, and F to the list of common keys, which no old time player I know plays in.

Bluegrass musicians may call their music “old-timey,” but old time musicians do not use that term. Old-timey bluegrass began in the nineteen thirties and forties with Bill Monroe and his crew, The Bluegrass Boys. But true old time, as stated by a friend and banjo player (PhD, Molecular Biology), “is the Top Forty of the eighteen forties!” Monroe was justified calling bluegrass–his genre–“old-time-y” because he derived it from true old time players he grew up knowing in Kentucky. In short, old time long pre-dates old-timey, and there is a whole generation of circa-WWII musicians and scholars, such as Mike Seeger, to thank for old time’s not going extinct.

Some bluegrass aficionados and C&W musicians seem genuinely perplexed by old time music. An old neighbor of mine, a Vietnam veteran and native Floridian (called Gator, of course), wanted to come over to the farm for one of our old time jams. He used to regularly attend monthly bluegrass sessions at a function hall in our town, so he was excited to come over and listen to one of our sessions.

After the group played the melody a few times around, Gator suddenly burst out, “OK, take a break!”

Forgetting all about bluegrass protocols, I said, “I need a break, all right,” and stopped playing. In bluegrass jam sessions, the instruments all take turns soloing for a few measures–these are the “breaks”–before gathering up for a last time around the whole tune and ending. This is anathema in old time. We play together in unison–over and over, like some religious ritual–until we’re exhausted, and the foot goes up and we all “go home.” Truth be told, this perplexed Gator, who was used to high-octane bluegrass ensembles. We players were in our element, however. I miss ole Gator, a true bluegrass fan, who died about ten years ago.

After my dad’s funeral last summer, I met up with a friend from my boyhood, who performs with his country & western band in clubs throughout Northwest Ohio. He wanted to get together in my youngest brother’s garage to play a few tunes on his guitar with me. He learned the chords to “Sally Ann” pretty damn quick:

D–/D–/D–/D–/D–/D–/A–/D–

He, too, seem perplexed by old time. After we had ripped through a few fiddle tunes, the penny dropped and he said, “This is festival music.” I would not disagree, though I am of a disposition generally to avoid festivals and fairgrounds.

I think of old time as the perfectly American genre of music. It blends dance melodies imported from the British Isles played on the fiddle with syncopated rhythms played on an African stringed gourd-on-a-stick. As slave-holder Thomas Jefferson famously noted, “the instrument proper to them is the Banjar, which they brought hither from Africa.” I’ve often wondered if the banjo joke didn’t arise out of the tacit awareness that this was originally the instrument of the enslaved. Through the abomination known as minstrelsy, this African banjar was eventually adopted by white musicians, and it promptly underwent adaptive radiation into all its current forms. Likewise, and ironically, there is a nearly forgotten tradition of black fiddlers who played dance halls throughout the old south but whose performances, alas, were rarely recorded. This hybridization of black and white musical traditions has yielded a simple yet beautiful thing: old time square dance music.

A gentleman is someone who knows how to play the banjo and doesn’t. (Mark Twain)

A division in banjo styles marks the divergence between the two species, old time and bluegrass. Bluegrass players in the Earl Scruggs mode pick furiously with finger picks on resonator-backed banjos and kick up quite a racket. The effect is rather dulcimer-like and unnerves me after a while. Old time players “frail” their open-back banjos in clawhammer style and keep a sock or hankie balled up behind their dowel stick to mute the sound. The effect is rhythmic, clucky, mesmerizing.

I prefer to play banjo with a synthetic wool sock balled up behind my dowel stick. I got the idea while busking on a street corner once years ago as a beginner banjo player. A gentleman came up to me and stood listening to me play for a while. When I had finished, I asked, “So, what do you think?”

“Put a sock in it,” he said.

[That would be my contribution to the genre of banjo jokes.]

What is it about the banjo, a lovely instrument, that provokes abuse? Only the viola and accordion are treated as poorly. It’s said that “perfect pitch” is the act of tossing a viola [banjo] into a dumpster without hitting the rim and striking the accordion inside.

The following symbolizes the flashpoint between bluegrass and old time banjo players: If someone asks you, “Can you play the theme from ‘Deliverance’?”, the old time answer is not just “No” but “Hell no, that’s bluegrass!” The request is for “Dueling Banjos,” a plagiarized version of “Feudin’ Banjos,” which has become an ode to forced buggery because of that film. (At least the original composer, Arthur Smith, won his lawsuit against the filmmakers and eventually got royalties.)

Making such a request of an old time banjo player will at the least evoke sudden deafness. Likewise, “Paddle harder: I hear banjos!” is not an old time joke, it’s making fun of bluegrass. They’re not the same. High-volume bluegrass banjo is to rhythmic old time banjo as Sheetrock is to horsehair plaster.

Hussey is at present tormenting [us] with his six known tunes on his banjo. [Source.]

Unlike the momentously diverse physical types of banjos, an old time fiddle is really just a violin, as it is in bluegrass, but the style is vastly different: simple, melodic, buzzy, scratchy, repetitive. Did I say scratchy? I find this to my liking: the technique is easily practiced. Back when I started, all I would have to do is remove my fiddle from its case and the cats would get up and leave the room.

There are no “breaks” or solos in old time. Just melodies. The lead fiddler shouts out the key, “A,” and some wag might respond, “Eh? Did you say A?” Then, as banjo players fuss over their instruments–some applying capos, others tuning up all five strings–the other fiddlers tune their own instruments to AEAE or “cross-tuning.” I discovered recently that this has a fancy Italian name, scordatura, which I am not sure how to pronounce.

Some common tunings in our group:

GDAE, or standard, for most C, G, and modal tunes

ADAE, or “high bass,” for most D tunes and a few A tunes

AEAE, or “cross-tuning,” for A tunes and only A tunes, like the crooked-ass “Jeff Sturgeon”

Less common ones:

GDGD “sawmill tuning” for A tunes played in G when you’re sick of playing them in A

DDAD “D-dad” (of course) for morbid and melancholy D tunes

ADAD for some versions of “Cumberland Gap” (D obviously is a favorite key)

AEAC# (rarely) “Drunken Hiccups” by the renowned fiddler Tommy Jarrell

If you’re playing to a crowd, it’s good to have some jokes on hand to tell between keys while the players are messing around with their pegs.

“What’s the difference between a banjo player and a savings bond? . . . A savings bond eventually matures and makes money.”

Being “secular” dance music, old time tunes tend to have cryptic or weird titles with bucolic themes (“Duck’s Eyeball,” “Forked Deer,”* “Great Big Taters in a Sandy Land,” “Dog Treed a Possum Up a White Oak Tree”) and silly lyrics:

Wish I had some sticks and poles

Build my chimney higher.

Every time it rains or snows

Puts out all my fire. “June Apple”Old Joe Clark he had a house

Fifteen stories high

And every story in that house

Was filled with chicken pie. “Old Joe Clark”

Words are less important than rhythm and speed when you want dancers to swing their partners into the walls.

The lead fiddler calls out tunes until the group has played just about every A tune they know. If we’re playing outside, spectators begin to dissipate.

Then the fiddler calls out another key.

“G.”

“Oh, gee. That’s not good….”

Some old time tunes are of a species because they tend to share phrases, “turnarounds,” and tags that can confound musicians after a while. You can almost swap out parts of tunes and put them together to form new tunes. “It’s modular!” the molecular biologist likes to say, as if speaking of nucleotide sequences. Tunes tend to blend together after a while, which may disconcert onlookers. This is not surprising: to outsiders, all bluegrass sounds the same, all jazz sounds the same, all classical sounds the same. The aficionado can make distinctions, though, as between various ales. It’s like Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace collecting beetles as boys: They could never get enough of them. They’re all the same! But different! Old time teaches us that variation on a theme is the key to life.

One of the most surprising discoveries I have made about the contemporary old time scene concerns its social profile. In 2002, I found myself in the mountains of West Virginia, amongst a mob playing hillbilly tunes from two centuries ago on instruments adopted by enslaved Africans and Scotch-Irish dirt farmers. But the people playing these tunes at such camps come from all over the States, not just Appalachia, and include professionals as well as amateurs, academics, and outside-the-mainstream artistes.

Yet it is a modest, low-key bunch. They have bumper stickers that say, “Old Time Music: It’s Better Than It Sounds,” and, “Give Me That Old Time. Keep Your Religion.” In spite of its very localized, Southern hill country origins, old time’s modern shepherds are surprisingly diverse. Although originally skewed toward males, women are now well represented in old time circles. (Except for the banjo camp I attended recently, which was like walking into the waiting room of a prostate health clinic. I don’t mean to sound rude; at 63, I fit right in.) Black players are busy resurrecting the African roots of the music. Over the years, through its various manifestations, our jam group has always harbored at least two examples each of lawyers, scientists, homosexuals, and Jews. (A little band I’m part of periodically plays a square dance gig at a synagogue in Portland. The wag in me likes to call it Hoedown, Moses.)

There is an undeniable element of escapism in embarking on the nearly insane task of learning how to play stringed instruments in middle age and finding the time to meet regularly with like-minded people. But when times are weird, time thus deserves to be wasted. It’s like forcing yourself to speak a new language just to drown out the gibberish you hear around you. Plunging into the mid-nineteenth century music scene may happily prompt an eschewal of the more sordid elements of modern life–vacuous television, mendacious advertising, deranged politics, (anti)social media, bottomless consumerism–all which I willingly throw to the dogs before making a mad dash for my fiddle. In such times, a life cobbled together with antique hobbies is an endurable life.

Homo sapiens is a queer species numbering in the billions, and there is a lot to fret about. So, when there are conspiracy theories afoot, go upstairs and practice your scales and bowing. If the latest delusion grips your friends or your children, find a new tuning on the banjo, study some tablatures, perfect your drop-thumb. When a new, human-induced environmental threat looms, have your bow re-haired, change your strings, learn a modal tune. When the din of politics gets to be too much, seek out your old time buddies, draw up your chairs in a tight circle, play, and maybe sing:

If a tree don’t fall on me I’ll live till I die.

Images

“Fiddlin’ Bill Henseley, Mountain Fiddler, Asheville, North Carolina by Ben Shahn, 1937 (LOC)” by pingnews.com is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0. Meme by the author.

Two Ben Guillemette fiddles. Photo by the author.

A portion of our friend Jim Atleson’s (1938-2022) banjo collection. Photo by Fiddlin’ David Stettler.

Outdoor jam on the farm. L-R: Jim, Cody, me. Photo by Fiddlin’ Donna Katsiaficas.