by Ashutosh Jogalekar

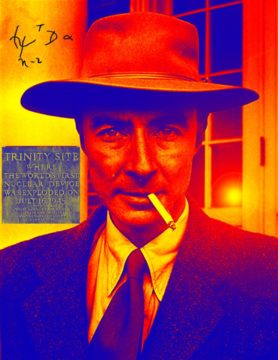

This is the seventh in a series of essays on the life and times of J. Robert Oppenheimer. All the others can be found here.

The Bohrian paradox of the bomb – the manifestation of unlimited destructive power making future wars impossible – played into the paradoxes of Robert Oppenheimer’s life after the war. The paradox was mirrored by the paradox of the arena of political and human affairs, a very different arena from the orderly, predictable arena of physics that Oppenheimer was used to in the first act of his life. As Hans Bethe once said, one reason many scientists gravitate toward science is because unlike politics, science can actually give you right or wrong answers; in politics, an answer that may be right from one viewpoint may be wrong from another.

In the second act of his life, like Prometheus who reached too close to the sun, Oppenheimer reached too close to the centers of power and was burnt. In this act we also see a different Oppenheimer, one who could be morally inconsistent, even devious, and complicated. His past came to haunt him. The same powers of persuasion that had worked their magic on his students at Berkeley and fellow scientists at Los Alamos failed to work on army generals and zealous Washington bureaucrats. The fickle world of politics turned out to be one that the physicist with the velvet tongue wasn’t quite prepared for.

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki horrified many of the Los Alamos scientists including Oppenheimer. Contrary to what some people believe, he did not regret building the bomb – the danger that Hitler would get one made that goal a perfectly reasonable one – but he did regret the fact that his beautiful physics had created a monster that could potentially destroy humanity, and he was very troubled by the faith which the politicians and generals seemed to be placing in it. Right after the news trickled in from Japan, he had entered a crowded auditorium at Los Alamos to cheers and applause, his hands clasped over his head like a victorious general. But just a few days later, after photos of the mutilated, burnt victims of the two unfortunate cities had changed jubilation to sober reflection and even revulsion, Oppenheimer wrote to his old Ethical Culture School teacher, Herbert Smith, “You will believe that this undertaking has not been without its misgivings; they are heavy on us today, when the future, which has so many elements of high promise, is yet only a stone’s throw from despair.”

He was, at that point, the most famous scientist in the world and a household name. His face would grace the covers of Time and Life magazine, the most popular subscriptions in the country. What he would do next was still a question, especially since so many possibilities remained open to him. Offers came rushing in from Harvard, Princeton and Columbia, but he chose to remain in California. Relations with Berkeley had become strained, however, in part because his old friend Lawrence who was much more sanguine about the bomb had little patience with his hand wringing. Nonetheless, even the Nobel Prize-winning physicist appreciated the importance of having a celebrity scientist on the faculty and urged the chair of the department to hire him. But Oppenheimer was ambivalent, and while keeping his chances at Berkeley open, accepted a position at Caltech where he found a warm welcome.

But Washington constantly beckoned and he found himself flying back and forth between the two coasts. In October, 1945, an opportunity arose to meet President Truman himself. The episode is one of history’s most ironic, showcasing the rift between the scientific and the political mind. Bohr and Oppenheimer had both seen what the politicians including Truman had not, that the only defense against a weapon which is essentially a weapon of genocide would be international cooperation; only three days after V-J Day, Oppenheimer had sent Stimson the conclusions of a final report written by the Scientific Panel of the Interim Committee: “We believe that the safety of this nation cannot lie wholly or even primarily in its scientific and technical prowess. It can be based only on making future wars impossible.” These were words right out of Niels Bohr’s mouth.

But Truman saw it differently; as far he was concerned, America should now use its monopoly on this new weapon as much to its advantage as it could. At the meeting, he told Oppenheimer that the country should first deal with the national situation – figure out authority and the rules of secrecy over the new weapons, that is – and then they should bother with what the international implications would be. But Oppenheimer saw it differently, telling the president that they must first define the problem internationally. Truman then asked how long it would take the Soviets to build the bomb. When Oppenheimer waffled the president leaned closer and said, “Never”. Oppenheimer did not quite know what to make of Truman’s response. Searching for words he said, in some anguish and with the drama he sometimes displayed, “Mr. President, I think I have blood on my hands.” Truman was startled, and one account has him offering Oppenheimer his handkerchief and saying, “Here, would you like to wipe it off?”. Another account has him saying, “Never mind, it’ll all come out in the wash.” An awkward silence followed, after which the two men shook hands and Truman told Oppenheimer he was hoping the physicist would help them all make sense of the new world they were in.

In reality Truman was infuriated. He later told Dean Acheson, the new Undersecretary of State, “I don’t want to see that son-of-a-bitch in this office ever again…blood on his hands dammit, he hasn’t half as much blood on his hands as I have. You just don’t go bellyaching about it.” Six months later he was still smarting from the exchange, calling Oppenheimer that “cry-baby scientist”. Truman, the autodidact country farmer from Missouri, had fundamentally misunderstood what the scientists had, especially when he mentioned his belief that the Soviets would never get the bomb: building the bomb was a question of resources, manpower and basic science. Any country with smart scientists and the will – and the Soviet Union certainly qualified – could figure it out within a few years. There was no big “secret” to keep. Citizens of the open republic of science, Oppenheimer, Bohr and their fellow scientists had understood this fundamental fact; the politicians had not. The Oppenheimer-Truman exchange, similar to the Bohr-Churchill exchange two years before, was symbolic of a continued misunderstanding between science and politics which would heat up the arms race between the two countries and, among other things, ultimately cause Oppenheimer’s downfall.

Never at a loss for eloquence, Oppenheimer met with a very different reception at Los Alamos that November when five hundred people crowded in to hear him speak. He spoke extemporaneously for an hour. What they had done, he said, was an “organic necessity.” “If you are a scientist, you believe that it is good to find out how the world works…that it is good to turn over to mankind at large the greatest possible power to control the world and to deal with it according to its lights and values.” But once the genie was out of the bottle, he proposed that they set up an international commission that was unhindered by national interests and controlled all aspects of atomic energy. Also agreeing that he disagreed with the president’s America-centric worldview when it came to nuclear weapons, he emphasized that “secrecy strikes at the very heart of science.” Oppenheimer was channeling Bohr here and already going against the official grain. The audience was mesmerized; more importantly they were reassured, feeling secure in the fact that the terrible weapon that they had built was for a reason.

But soon, his fellow scientists were to come to know how divided they felt about their former leader. One of the most important issues in the early history of nuclear weapons was the apportioning of authority between civilians and the military, a drama that has played out in the nuclear weapons programs of most countries. The army naturally wanted authority to rest with them, they wanted to enforce severe penalties for any leakage of classified information and wanted to cast a wide net on the research itself. But the scientists were horrified at the implications it would have for their work, not just work on the weapons themselves but in the basic areas of nuclear and atomic physics that they would continue to research in their universities; as Bethe put it, like good soldiers they had helped built the bomb, and now they wanted to go back to the world they best loved and do their science without interference.

A particular point of contention came in October, 1945, when two senators drafted a bill by their name called the May-Johnson bill that, among other things, would place key parts of atomic energy development under military purview and would severely penalize even accidental leakage of information. The bill also proposed to set up an Atomic Energy Commission, with a mix of civilians and military officials as commissioners. The scientists were almost unanimously opposed to it and looked to Oppenheimer to convey their concerns to congressmen and senators. Instead, in testifying about the bill before Congress, Oppenheimer proved himself to be a master of equivocation, first telling his fellow scientists that they should support the bill because – inexplicably, they thought – it would provide the first steps toward international control of atomic energy and then effectively passing the buck when asked by the Congressmen if he thought it was a good bill by saying that it should be sound since it was supported, among others, by Fermi, Lawrence, Compton, Bush and other distinguished scientists. As to the question about whether he thought military commissioners should head it, he said that he cared less about a man being in uniform than about what kind of a man it was.

Clearly Oppenheimer had not opposed the May-Johnson bill with the kind of vigorous advocacy that his friends and colleagues expected. At least some prominent scientists like Herbert Anderson (a protégé of Enrico Fermi), Robert Wilson and Leo Szilard said their faith in him had been shaken. Oppenheimer’s responses show how he was trying to tread the thin line between being a dissenter and being an insider. It was a line that would increasingly become hazy. As it turned out in this particular case, the May-Johnson bill metamorphosed into a watered down version called the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 that squarely placed atomic energy development under a group of civilian commissioners appointed by the president. For the moment, at least, the scientists’ fears proved largely unfounded.

As the year 1945 came to an end, Oppenheimer and the atomic scientists were filled with a mixture of hope and fear about their creations. The next year would prove highly consequential. Over Christmas, Oppenheimer visited his old friend Isidor Rabi in his apartment at New York City. As the two men looked out of the window at the ice floes lazily making their way down the Hudson river, they discussed a glimmer of an idea for a way to control the spread of nuclear weapons, one that would make its way into a revolutionary document that holds great import even today. At the beginning of 1946, Truman had asked Dean Acheson and the chairman of the new AEC, David Lilienthal, to draft a blueprint for dealing with the thorny problem. Acheson realized that he needed a group of technical experts to advise the committee. There was no more accomplished expert than Robert Oppenheimer who they could call upon. Over the next few months, the group engaged in a combination of scientific seminar and groundbreaking policy planning, with Oppenheimer leading them through a whirlwind tour of nuclear physics.

David Lilienthal, a sensitive, worldly man who had previously been the chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority, later called their meetings “one of the most memorable and emotional intellectual experiences of my life.”. That he thought this was in large part because of their scientific expert was evident. Lilienthal’s impression of Oppenheimer, then as later, verged almost on hero worship. Initially “greatly impressed by his flash of mind”, he wrote that Oppenheimer was an “extraordinary personage, a really great teacher”. He concluded his superlative assessment by later telling Oppenheimer’s lawyer that it was “worth living a lifetime just to know that mankind has been able to produce such a being.” Lilienthal’s assessment mirrors that of many of Oppenheimer’s students and colleagues, but in that fraught beginning of the Cold War, it would increasingly become a rarity.

The report that the group authored, with the wording largely supplied by Oppenheimer, came to be known as the Acheson-Lilienthal report. It was a radical document. Knowing what Bohr had said about an open culture of science and realizing the practical difficulties of policing individual nations’ nuclear infrastructure, the report suggested that every aspect of atomic energy, from the mining of uranium to the production of fissile material would be under the control of an international organization like the newly formed United Nations. Even more radically, because peaceful uses of nuclear energy cannot be neatly separated from malicious uses, the organization should deliberately spread mines and processing plants in different countries while continuing to have complete control of them – in effect peacefully proliferating them. One of the most insightful parts of this arrangement was that the world did not need to wait for a country to make bombs in order to gauge its ill intent; merely opening a mine would foreshadow such an action. Just like science is done in the open, so would the development of nuclear energy. As Richard Rhodes says in his book “Dark Sun“, the Acheson-Lilienthal report advocated the equivalent of a batch of disassembled guns, all of which are within reach of every country but all of which are watched and controlled by an international authority like the United Nations. It is only in the knowledge that nobody else can build bombs is a country secure. More than once the report also channels Bohr by saying that true security is incompatible with secrecy. When the Danish Nobel laureate saw the report he remarked that it offered “just the best hopes for the development in which we all put our faith.”

Unfortunately the radical report was doomed to die a slow and painful death. Truman’s goal was to present it to the Soviets at the United Nations. As presenter he picked a 76-year-old financier and former business partner of Secretary of State James Byrnes, Bernard Baruch. When Baruch took a look at the report and saw its internationalism he blanched; he accepted his appointment conditional on radically modifying the radical document. Baruch wanted a policy of ‘swift and sure punishment’ to be part of the proposal, along with a condition that other countries promise not to develop nuclear weapons before the United States did. When he presented it at the United Nations, the Soviets predictably and promptly rejected the hard-line wording. Oppenheimer later said that the day he knew who was going to present the report was the day he gave up hope.

It did not help that dark clouds were gathering on the horizon in 1946. Three signal events guaranteed the speedy inauguration of the Cold War that year: the first was George Kennan’s famous “X” telegram from the American embassy in Moscow in which he laid out his containment policy, a policy that had an enormous impact in Washington but that was also given a highly militarist meaning unintended by Kennan; the second was Churchill’s famous “iron curtain” speech at Fulton College in Missouri; and the third was a rousing speech by Stalin in which he declared the Soviet system, freshly victorious from having beaten the Nazis, on its way to world domination. In this atmosphere, any kind of international proposal seemed doomed to fail. Later events like the Berlin blockade made mutual cooperation with the Soviet Union even more inconceivable; after seeing a 1949 proposal by Oppenheimer, Acheson said he failed to see how one could encourage a foe as zealous and aggressive as the Soviet Union to ‘disarm by example.’

For now Oppenheimer’s star was still high. In the fall of 1946, he was unanimously chosen to be the chairman of the General Advisory Committee (GAC) of the AEC, a position that effectively made him the top advisor on nuclear matters in the country. It was also during this time that a character enters Oppenheimer’s life who was going to become his arch nemesis and have enormously destructive consequences for his career – Lewis Strauss. Strauss is one of the most remarkable people of this era, not because there was much that was admirable about him but because of how much bad advice he could give from influential positions, much like Oppenheimer’s fellow physicist Edward Teller.

A former shoe salesman with a high school education, he had somehow weaseled his way into becoming Herbert Hoover’s assistant when Hoover was in charge of food relief in Europe after the Great War. Impressed by the young assistant’s work ethic and ambition, Hoover had introduced him to a well-heeled law firm in New York City where he quickly rose through the ranks, at one point making a million dollars a year; marriage to the daughter of one of the firm’s founders had made him a part of the elite establishment. By shrewdly withdrawing his investments before the crash of 1929, Strauss (who insisted people pronounce his name as “Straws”) had become financially independent and on the lookout for talent and opportunity. While not a physicist himself, he followed the seminal discoveries in nuclear physics in the 1930s with great interest and fancied himself something of a physicists’ patron; at one point he was in regular touch with and supported the young Leo Szilard and his maverick ideas about nuclear fission. Strauss was a vindictive, thin-skinned man who often took disagreement as personal affront. “If you disagree with Lewis the first time”, a colleague said, “he will think of you as a fool. But if you disagree a second time, he will probably think you are a traitor”.

Strauss meeting Oppenheimer was like an ill-fated Greek tragedy destined to crash on the rocks. But at least at the beginning, Strauss was as impressed with the physicist as anyone else and knew his stature in the community. He was instrumental not just in supporting his appointment as GAC chairman but also offered him the directorship of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton; a move to Princeton from California would make it easy for Oppenheimer to travel to Washington. As part of his GAC appointment, Oppenheimer had to be cleared for a top-secret security clearance. During the background investigation Strauss learnt about his role in the “Chevalier affair”, but since he had been cleared during the project in spite of it, Strauss did not think much of it. The Chevalier affair again came up in 1946 when the FBI questioned Oppenheimer about it in the wake of increasing anti-communist sentiment; FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had kept Oppenheimer under one kind of surveillance or another since the end of the war. Significantly during this questioning, Oppenheimer told the FBI that he had made up the story about the three sources in 1943 (detailed in this post) and there had been only one source. In fact Oppenheimer had divulged the name of this source to General Groves during the war – his friend Haakon Chevalier. That Oppenheimer never told Chevalier about his discussions with security agents reflects very poorly on him; it was only much later – after Chevalier had been subjected to hours-long questioning and denied jobs in the United States that had forced him to move to Paris, all because of Oppenheimer’s testimony – that Chevalier who virtually worshipped Robert came to know about what can only be described as betrayal on his friend’s part.

Chavelier was not the only one who had to suffer the consequences of Oppenheimer’s betrayal. In 1949 the Cold War started heating up and anti-communist sentiment in the United States started building up to hysteria. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had been established in 1938 and was ostensibly formed to address threats that “attacked the form of our government as guaranteed by our Constitution”, a vague clause that virtually ensured that HUAC would function as a giant vacuum cleaner, sweeping up ‘subversives’ and erasing the distinction between incendiary speech and thoughts and actual subversive action. Because physicists were at the nucleus of secret atomic energy work, many of them were caught in HUAC’s dragnet. Much before Joe McCarthy made it fashionable, almost anyone who had been a former member of the communist party was subpoenaed and called to testify before the committee. Many of Oppenheimer’s former students including David Bohm, Joseph Weinberg, Bernard Peters and Rossi Lomanitz had been party members.

The case of Bernard Peters, a talented cosmic ray physicist who had been Oppenheimer’s PhD student in 1942, is particularly instructive. On June 7, 1949, Oppenheimer was called to testify before the committee. Under questioning, while denying that he himself had ever been a member of the party, he admitted that Peters was “quite the red” and a “crazy person”. At that time Peters was employed by the University of Rochester. Somehow Oppenheimer’s secret testimony was leaked, leading to outrage among his colleagues; as far as they could tell, far from protecting his former student, he had thrown him under the bus. Two of Oppenheimer’s closest colleagues and friends, Hans Bethe and Victor Weisskopf, were mortified and begged Oppenheimer to write a letter clarifying his words. Peters himself went to meet Oppenheimer with Frank Oppenheimer and came back dismayed. Oppenheimer wrote a kind of partial retraction which did little to exonerate Peters. Fortunately the University of Rochester, in a gesture that was all too rare during those paranoid times, not only did not fire Peters but gave him tenure. Worse was the fate of Bohm, Lomanitz and Weinberg, all of whom pleaded the fifth in front of HUAC, were fired from their respective jobs and had trouble finding jobs in the United States. Bohm later moved to England and became a distinguished philosopher and writer who collaborated with the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti and the Dalai Lama, and Peters to India where he worked at the Tata Institute for Fundamental Research in Mumbai. In no case did their former teacher mount a vigorous defense of his former students.

Worst was the fate awaiting Frank Oppenheimer who by this time had been a professor at the University of Minnesota. Frank had denied he had been a communist party member earlier to a congressional committee and to security agents; now, instead of pleading the fifth as many questioned by HUAC did, he decided to tell the truth that he had been a party member. In short order he was fired by his university. Later in his life Frank became a rancher and physics professor and, most famously, the founder of the Exploratorium in San Francisco. These episodes indicate that by this time Oppenheimer was a dedicated government insider and had also grown fearful of the political climate, all of which led him to implicate former students and colleagues to save himself. It did not endear him to his colleagues, even as he was becoming suspect for his views on nuclear weapons to the Washington establishment.

The prime candidate for holding Oppenheimer’s views suspect was Lewis Strauss. In front of a Congressional panel in June, shortly after Oppenheimer’s testimony implicating Peters, the always paranoid Strauss expressed concern that the United States was exporting nuclear material to other countries. The material in question was radioactive isotopes for industrial testing and other peaceful applications of atomic energy. Oppenheimer was asked whether he agreed with Strauss’s contention that the material posed a security risk. Exasperated by Strauss’s position – almost any material is what we now call “dual use” – Oppenheimer retorted, “You can use a shovel for atomic energy; in fact you do. You can use a bottle of beer for atomic energy; in fact you do…My own rating of the importance of isotopes is that they are far less important than electronic devices, but far more important than, say, vitamins, somewhere in between.” His withering sarcasm had drawn laughter from everyone except one man – Strauss’s eyes flashed and the color rose in his face. Oppenheimer was known to be cruel to his peers, but while most of them either ignored the taunts and insults, Strauss was not one to forget slights.

In August, 1949, the country’s fate took a dramatic turn when the Soviet Union exploded their first atomic bomb. Unlike the scientists who knew the caliber of the science in Russia along with Stalin and his henchman Lavrenty Beria’s iron grip on their scientists, the test threw the politicians and generals who had expected that Russia would not get a bomb for at least several years more in a frenzy. Suddenly the fixation on an even bigger bomb – a thermonuclear bomb – took center stage. Unlike a fission bomb which depends on assembling enough plutonium or uranium in a critical mass, a thermonuclear or hydrogen bomb depends on using heat as the trigger for fusing deuterium or tritium nuclei together. Unlike a fission bomb there’s no real upper limit for a hydrogen bomb, so in principle it could be made indefinitely large. In addition, unlike plutonium and uranium, deuterium and (to a lesser extent) tritium were cheap. While the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki had yielded the equivalent of about 20,000 tons of TNT, hydrogen bombs were predicted to yield 10 million or even 100 million tons of TNT. These were numbers that were beyond anyone’s imagination, but until then they had been theoretical. Now the time seemed ripe to one man in particular to turn them into reality – Edward Teller.

Since the end of the war, the volatile Hungarian-born physicist had bided his time and worked as a professor at the University of Chicago alongside his mentor, Enrico Fermi. The hydrogen bomb had been an idée fixe for a long time – Teller had suggested the idea to Fermi as early as 1941. He had then brought it up at the Berkeley conference organized by Oppenheimer in 1942. It was Teller’s unwillingness to work on the fission bomb and his obsession with the thermonuclear that led Oppenheimer to excuse him from working in the theoretical division during the war and let him work on his pet project. In one form or another Teller had been gestating the idea since the end of the war, watching from the sidelines as his former boss gained prominence in government. The problem was that Teller’s original idea imagined an atomic bomb generating enough heat and igniting a mass of deuterium or tritium that would sustain burning. Preliminary calculations had shown that there was no guarantee that the fuel could be ignited, nor that it would continue burning once ignited. Now Teller saw his opportunity and started lobbying with influential scientists and government and military officials.

Oppenheimer meanwhile saw a great danger in the paranoia that was gripping the country regarding the Soviet test. The United States still had a significant lead in atomic weapons; by 1950 the country was thought to possess about 200 bombs in its arsenal. This was enough to wipe out the Soviet Union several times over. But the Air Force in particular, goaded by the Strategic Air Command (SAC) and its commander Curtis LeMay, was clamoring for more. Oppenheimer decided to organize a meeting to enshrine official GAC policy regarding thermonuclear weapons; it was scheduled for the end of October, on Halloween. Oppenheimer had already had talks about the hydrogen bomb with James Conant, wartime administrator of the Manhattan Project and by now a close friend; “Uncle Jim”, as Oppenheimer called him, was opposed to building the ‘Super’ (as the bomb had been christened) in even stronger terms than Oppenheimer himself. “What worries me”, confessed Oppenheimer to Conant, “is that this thing seems to have caught the imagination, both of Congressmen and of the military people, as the answer to the problem posed by the Russian advance.” In short, Oppenheimer was worried that the country was going to get so fixated on the Super that it would forestall all other ways to scale back a nuclear arms race.

Meanwhile Teller had started lobbying scientists to go back to Los Alamos and start working with haste on the weapon, inaugurating another Manhattan Project-style effort. He tried to recruit Oppenheimer who flatly refused. He also tried to recruit his old friend and colleague, Cornell physicist Hans Bethe who commanded authority and expertise that few could match. Bethe had at first said he would consider joining the project. A few weeks before the Halloween meeting, Teller and Bethe went to see Oppenheimer at Princeton and to seek his advice. Teller was concerned that Oppenheimer with his well known powers of persuasion would convince Bethe not to work on the bomb. But Oppenheimer told the two men he was still undecided. He showed them a letter from Conant saying that they would build the Super “over my dead body.” As the men were leaving, Bethe said to Teller, “You see, I am coming after all.” But after the meeting, Bethe happened to run into two old friends at another meeting, the physicists Victor Weisskopf and George Placzek. Weisskopf, an uncommonly conscientious scientist, painted a vivid picture of how the world would look like if the hydrogen bomb were developed and used, how such a world would not be worth preserving even if one side technically “won”. Bethe was moved by Weisskopf’s arguments. After going home he called Teller and told him he was not coming after all. Teller became convinced that Oppenheimer’s velvet tongue had swayed the Cornell physicist’s mind.

The Halloween meeting opened on a Friday and went on until Sunday. Present, among others, were Oppenheimer, Lilienthal, Rabi, Fermi and Conant. The document they produced is an extraordinary one. Reading it one gets a sense of a tremendous missed opportunity, an opportunity clearly seen by men who were admittedly the foremost thinkers on nuclear matters in the country. While Oppenheimer had his own bias about the project, there is every indication that he did not try to force anyone’s hand and gave everyone complete freedom to air their views. The meeting produced two parts, a majority view and a minority view. The consensus view argued that precious neutrons that would be spent in breeding the tritium that is needed as fuel for the super could be spent instead in making plutonium and producing smaller, tactical nuclear weapons. But there was also a strong moral conclusion that the GAC reached. The majority view that was signed by Oppenheimer said,

“It is clear that the use of this weapon would bring about the destruction of innumerable human lives. It is not a weapon which can be used exclusively for the destruction of material installations of military or semi military purposes. It’s use therefore carries much further than the atomic bomb itself the policy of exterminating civilian populations… we believe a super bomb should never be produced. Mankind would be far better off not to have a demonstration of the feasibility of such a weapon until the present climate of world opinion changes.”

The most remarkable part of the document, however, is the minority view signed by Rabi and Fermi. It said that:

“Necessarily such a weapon goes far beyond any military objective and enters the range of very great natural catastrophes. By its very nature it cannot be confined to a military objective but becomes a weapon which in practical effect is almost one of genocide… The fact that no limits exist to the destructiveness of this weapon makes its very existence and the knowledge of its construction a danger to humanity as a whole. It is necessarily an evil thing considered in any light.”

Later, when Oppenheimer was accused of opposing the hydrogen bomb, his detractors seemed to have conveniently forgotten that Rabi and Fermi, not to mention Conant, had opposed it in even stronger terms.

The important GAC report had the predictable effect on the state department and the White House – almost none. Acheson could not understand how one was to persuade a regime like Stalin’s to not develop the hydrogen bomb even if the United States did not; he did not understand what the GAC understood, that not developing and testing the weapon would give high moral ground to the country, and even if the Russians built and tested one, the United States’s very significant lead in fission weapons – a lead which would not last forever if both countries refrained from signing an agreement – would easily allow the country to threaten its adversaries and retaliate. As it happened, goaded by Acheson, Strauss and others, Truman had already made up his mind, ignoring both the moral and the technical considerations. On January 31, 1950, he announced that he had authorized the AEC to resume work on all nuclear weapons, including the Super. Said Rabi about the president who was famous for his decisiveness, “I never forgave Truman”. How much the world lost by not taking advantage of that narrow window of time when the hydrogen bomb was not reality and the United States had a lead in atomic weapons would never be known, but it is surely one of history’s greatest lost opportunities.

Oppenheimer and Conant were so distraught by Truman’s decision that they considered resigning from the GAC; if they had their life trajectories would almost certainly have been happier, and in retrospect, the development of nuclear weapons in America’s arsenal would have continued unabated. “This is the plague of Thebes”, Oppenheimer said to a reporter at a party thrown shortly after Truman’s announcement to celebrate Strauss’s birthday. When Strauss introduced Oppenheimer to his son, the physicist snubbed him by extending a hand over his shoulder. Strauss was understandably furious.

As Oppenheimer and other physicists knew, and as Truman did not, nobody knew if a hydrogen bomb would work when the president made his announcement. Calculations by Fermi, John von Neumann and the brilliant Polish-born mathematician Stanislaw Ulam showed well into 1950 that thermonuclear burning could not be sustained, even with very large quantities of tritium. It was only in June 1951, based on a groundbreaking idea by Ulam that Teller expanded on, that hydrogen bombs became reality. Oppenheimer’s opponents also tended to forget that once he knew the idea behind what became known as the Teller-Ulam invention, he called it “technically sweet” and encouraged its development. This story is wonderfully told in Rhodes’s book, “Dark Sun”.

From then on a very clear dividing line had appeared between the establishment scientist and the establishment. It did not help that after Truman had made his announcement, theoretical physicist Klaus Fuchs who had worked at Los Alamos under Oppenheimer confessed to passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. Fuchs was talented and highly placed enough to have given them valuable information, although when it came to the thermonuclear, the ideas that he had – based on Teller’s design – were so premature and wrong that Oppenheimer actually hoped that he had passed on those ideas to the Russians to mislead them.

In the spring of 1951, Oppenheimer was assigned to give advice on a top secret project organized by the Air Force called Project Vista, held at the Vista Arroyo hotel near Caltech. The president of Caltech, Lee DuBridge, led the group, but Oppenheimer was invited to contribute as an expert. The aim of the project was quite general, to assess improvements in air and ground warfare. It made many recommendations including how the air force could better support the army through improved communications, but one chapter in particular, Chapter 5, became the focus of Oppenheimer’s opponents. It had been written almost exclusively by him and recommended that NATO diversify its atomic arsenal, not through hydrogen bombs but through tactical atomic bombs that would be primarily used by ground forces, not air forces. This was a direct rebuke to the doctrine of SAC which advocated massive attacks on the Soviet Union using strategic weapons.

Oppenheimer’s manuever was aimed at taking authority away from the Air Force and SAC because their plan for bombing the Soviet Union in 1951 absolutely appalled him, relying as it did on targeting every Russian city with strategic weapons so many times over that, as Churchill would say in a different context, it would “make the rubble bounce”. “The Air Force plan in 1951 was the goddamndest thing I ever saw”, he would later tell Freeman Dyson. But Air Force officials were furious with what they saw as Oppenheimer taking away authority and funding from them. Thomas Finletter, Secretary of the Air Force, declared that Oppenheimer should never be asked to advise a panel on classified projects again. As Ken Young and Warner Schilling lay out in detail in their book, “Super Bomb“, much of Oppenheimer’s troubles can be seen through the prism of the interservice rivalry between the Army and the Air Force whose cross-hairs he had been caught in. He was also both naive enough and arrogant enough at the same time to underestimate the damage Air Force officials could do to him.

It was clear by the time the first hydrogen bomb – a leviathan consisting of a giant tank of liquid deuterium that exploded with a force more than six hundred times that obliterating Hiroshima – had been tested in November, 1952, that the two superpowers were well on their way to a ruinous and terrifying arms race; by the end of the Cold War, the United States had built 70,000 nuclear weapons at a staggering cost of $5.5 trillion, an arsenal that went infinitely past deterrence and could have destroyed the planet many times over. The decision to make the hydrogen bomb appeared, even then, irrevocable, a tipping point in mankind’s ability to pull down the temple on itself.

It would have been better if Robert Oppenheimer had retired from his government job by the end of 1952. His valiant and sensible efforts to forestall the arms race had failed, and with a Republican administration in place, it wasn’t clear that he could do much. But he had tasted power and known what it was like to be an insider. That taste would soon turn bitter. In February, 1953, Oppenheimer gave a speech in New York at the Council for Foreign Relations, a venue that would guarantee attention in the upper echelons of New York and Washington. Oppenheimer’s speech was an unclassified version of a report he had penned with future JFK advisor McGeorge Bundy and sent to the Eisenhower administration. Channeling Niels Bohr again, the report advocated a policy of “candor” in which Americans should be told the extent of the atomic enterprise, including the rate of production of bombs. The New York address now took direct aim at the notion of secrecy. “We do not operate well when the important facts are known, in secrecy and fear, only to a few men.” He criticized (now ex-president) Truman and a “high officer of the Air Force” (chief scientist David Griggs who had been incensed at his recommendations on Project Vista) for underestimating Soviet capabilities and thinking that they could protect the country’s striking force without somehow harming the country. The speech seemed like a direct rebuke to officials in multiple places. Oppenheimer seemed to be ridiculing the very foundation of the establishment’s nuclear weapons policy, striking at the heart of secrecy and criticizing the government for thinking that a war with nuclear weapons could be won. Unsurprisingly, many including Lewis Strauss were appalled.

At the end of the speech, Oppenheimer provided a striking, memorable analogy for the continued standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union: ““We may be likened to two scorpions in a bottle, each capable of killing the other, but only at the risk of his own life.” Now the scorpions around Oppenheimer himself would start moving in for the kill.

In May, 1953, Strauss began an orchestrated campaign to get rid of Oppenheimer’s influence. He gave Eisenhower a kind of ultimatum; he could not serve on the AEC if Oppenheimer were to stay. Eisenhower himself was troubled by what he saw as Oppenheimer’s “almost hypnotic power over small groups” as he briefed a group of White House officials on “candor” and what he had said in his New York talk. In retrospect, the evidence clearly shows that Strauss repeatedly and deliberately misled the president – who clearly had other issues on his mind – as to what he labeled as Oppenheimer’s untrustworthiness and opposition to the hydrogen bomb. Strauss’s case was helped by a vicious, opportunistic character named William Borden who was the executive chairman of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy. Borden had held a grudge against Oppenheimer for some time. Now, in the poisonous atmosphere of Joe McCarthy’s America, he sent a letter to the FBI laying out charges against the physicist and concluding, fantastically, that “more probably than not J. Robert Oppenheimer is an agent of the Soviet Union.” When the FBI report containing Borden’s allegations reached Eisenhower he was shocked and, pending investigation, ordered a “blank wall” to be placed between Oppenheimer and classified information. Strauss now had Oppenheimer i his corner. He summoned the physicist to a meeting in December and told him that his security clearance had been taken away, and that if he wanted he could either resign or could request a hearing.

This was a fork in Oppenheimer’s life. When the shocking news became public, Einstein told a reporter that he thought that Oppenheimer should go to the government, tear up his clearance, tell them they were fools and resign. As usual Einstein saw through the thicket of complexity to the heart of the matter. But such behavior would have been entirely out of character for Oppenheimer. After conferring with his lawyers, Oppenheimer decided to fight the charges.

The classified papers in Oppenheimer’s case were taken away and he was served the official letter from the AEC outlining the accusations. Hardly anything in there was new, and the Chevalier affair featured prominently. Except for the charges related to obstructing the hydrogen bomb, all the other charges were ones explicitly addressed – and rejected – by General Groves during the war and by the AEC during Oppenheimer’s appointment to the GAC. This should have been easy, but Strauss made sure that it would not, especially by his choice of prosecutor, a canny forty-six-year old trial lawyer named Roger Robb who had won convictions in murder trials. Robb was a street fighter who brought a gun to a knife fight. In contrast, Oppenheimer’s team picked someone who would bring a walking stick to a gun fight. Lloyd Garrison was a genteel, distinguished lawyer at a prestigious New York law firm, skilled in debate but not a street fighter (the contrast reminds one of the much later contrast between the dignified Warren Christopher and the cunning James Baker during Bush v. Gore). Strauss also ensured that since the case would discuss classified material, the security clearances that Oppenheimer’s lawyers would need would be delayed.

The trial which opened on April 12, 1954, was exhibit A in the travesty of justice, the kind of show trial which would have been completely at home in the Soviet Union; an especially ironic fact since Oppenheimer’s adversaries were accusing him of having communist leanings. The board was chaired by Gordon Gray, president of the University of North Carolina. Almost everything about the “inquiry” by the Gray board, as it was euphemistically called, was illegal. Not only were Oppenheimer’s lawyers denied access to the prosecutors’ material under the pretext of national security – they were asked to leave the room when this material was presented – but his home as well as his lawyers’ offices were bugged by the FBI, ensuring that Hoover and Strauss knew the details of what he and his lawyers were discussing. For Oppenheimer and his team, it was downright Kafkaesque.

Remarkably, the powers of persuasion that Oppenheimer was known for seemed to have deserted him in his hour of deepest need. Most of the time he sat chain-smoking on a couch, and when he testified multiple times his usual eloquence devolved into mumbling and equivocation under the ruthless scalpel of Robb’s legal talents. The major points of contention were the Chevalier affair and what it indicated about Oppenheimer’s character. Oppenheimer was asked to remember facts from more than ten years ago. All the usual associations were dragged out – his affair with Jean Tatlock, his associations with students who were known communists, and most prominently his lying to security agents. At one point when Robb asked him why he had reported three advances instead of one advance to security agents, the best Oppenheimer could do was to say, “Because I was an idiot.” As historian Richard Rhodes comments, the transcript of the whole affair is “one of the great, dark documents of the early atomic age, almost Shakespearean in its craven parade of hostile witnesses through the government star chamber, with the victim himself, catatonic with shame, sunken on a couch incessantly smoking the cigarettes that would kill him with throat cancer at 63 in 1967.” It was a terrible performance.

Better than Oppenheimer on the stand were some of the star witnesses his lawyers had lined up. This included the usual suspects – distinguished scientists like Fermi, Bethe, Rabi and Conant – but also government and military officials including Groves, John McCloy who had Eisenhower’s ear and, surprisingly enough, John Lansdale, the security officer who, after talking to Oppenheimer at Los Alamos in 1943, had become convinced of his patriotism and loyalty. Ernest Lawrence phoned Strauss to say he could not attend because of an attack of colitis that seems to have been at least partly psychosomatic; while Lawrence was a confirmed political adversary of Oppenheimer’s by this time, one wonders if his ailment was brought on by thoughts of testifying against his former friend, the man he had built up Berkeley to world prominence with starting all the way back in 1929.

Kitty Oppenheimer also testified about her own background; during this time she seems to have been a rock to Robert. But many of the witnesses saw themselves get caught in contradictions and guilty-by-association tactics skillfully employed by Robb. When Bethe testified at length about Oppenheimer’s great contributions to national security, Robb could not, as a passing shot, resist asking him whether Klaus Fuchs was in his division. When McCloy – one of the most respected financiers and political advisors in the country – discounted the Chevalier affair, Robb tried to trip him up by getting him to admit that he wouldn’t hire a person with Oppenheimer’s associations in one of his banks. Groves was a particularly interesting witness. While he admitted that hiring Oppenheimer in 1942 was a matter of expediency and perfectly valid under that era’s security rules, he would not clear the physicist in 1954 based on the new security rules.

It is an indication of Oppenheimer’s stature that even scientists and officials like John von Neumann and Groves who had been politically opposed to him testified on his behalf. These men understood that disagreement does not equate disloyalty. But the most ringing blow to the charade was delivered by tough-minded Isidor Rabi who had grown up on the streets of New York and could face any adversarial questioning.

“Q. Dr. Rabi, Mr. Robb asked you whether you had spoken to Chairman Strauss in behalf of Dr. Oppenheimer. Did you mean to suggest in your reply – in your reply to him you said you did among other things – did you mean to suggest that you had done that at Dr. Oppenheimer’s investigation?

A. No; I had no communication from Dr. Oppenheimer before these charges were filed, or since, except that I called him once to just say that I believed in him, with no further discussion.

Another time I called on him and his attorney at the suggestion of Mr. Strauss. I never hid my opinion from Mr. Strauss that I thought that this whole proceeding was a most unfortunate one.

Q: What was that?

A: That the suspension of the clearance of Dr. Oppenheimer was a very unfortunate thing and should not have been done. In other words, there he was; he is a consultant, and if you don’t want to consult the guy, you don’t consult him, period. Why you have to then proceed to suspend clearance and go through all this sort of thing, he is only there when called, and that is all there was to it. So it didn’t seem to me the sort of thing that called for this kind of proceeding at all against a man who had accomplished what Dr. Oppenheimer has accomplished. There is a real positive record, the way I expressed it to a friend of mine. We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it, and what more do you want, mermaids? This is just a tremendous achievement. If the end of that road is this kind of hearing, which can’t help but be humiliating, I thought it was a pretty bad show.”

Edward Teller, on the other hand, knew exactly what he wanted to say. In 1951, Teller had approached the FBI and had told them that he would “do anything possible” to see Oppenheimer’s services terminated. He saw Oppenheimer’s hand and his powers of persuasion everywhere. Before the hearing, Hans Bethe had tried hard to convince him not to testify; Freeman Dyson remembers encountering Bethe in Washington and hearing from him that he had just had “the most unpleasant conversation of his life, with Edward Teller.” Now Teller provided a view of Oppenheimer that was calculated to be subtle and yet devastating:

“In a great number of cases, I have seen Dr. Oppenheimer act – I understand that Dr. Oppenheimer acted – in a way which for me was exceedingly hard to understand. I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated. To this extent I feel that I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better, and therefore trust more.”

When asked if he thought Oppenheimer’s security clearance should be reinstated, Teller said that he didn’t think so, especially based on actions since 1945. Freeman Dyson later said that without Teller’s testimony the outcome would not have been changed, but Teller remains the most prominent scientist to have testified against Oppenheimer.

As Rabi said, it had been a pretty bad show. At the conclusion of the trial, the board voted 4-1 to deny Oppenheimer’s clearance, only 32 hours before it was due to expire anyway. Ward Evans, a chemistry professor at Northwestern University, said that the debacle would always be a “black mark on the escutcheon of this country.” The trial had been a deliberate, orchestrated attack by Lewis Strauss and his associates on a patriotic American who had contributed immensely to protecting his country against adversaries and laying out a bold vision for averting a disastrous arms race that had been ignored. Oppenheimer’s influence with the United States government had ended. Early this year, 68 years after the fact, the Department of Energy symbolically reversed the removal of Oppenheimer’s security clearance, arguing that the AEC had violated their own rules.

As it turned out, at least two of his prominent opponents reaped what they sowed. Lewis Strauss faced a barrage of humiliating, adversarial questioning, much like Oppenheimer’s, when he appeared for confirmation as Commerce Secretary before the Senate in 1958, having been nominated by Eisenhower. He was accused of lying and exaggerating under oath and his nomination was rejected, the first time that had happened since 1925. From Princeton Oppenheimer watched Strauss’s downfall.

Most of Oppenheimer’s colleagues were so outraged at Edward Teller’s testimony that he was virtually expelled from the community of physicists he had known and loved for so long. Teller died in 2003 at the ripe old age of 95, still trying to take credit for inventing the hydrogen bomb and defending his testimony against Oppenheimer. He was outlived by his old friend, Hans Bethe.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer”, 2005

- Richard Rhodes, “Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb”, 1995

- Priscilla McMillan, “The Ruin of J. Robert Oppenheimer”, 2007

- Ken Young and Warner Schilling, “Super Bomb: Organizational Conflict and the Development of the Hydrogen Bomb”, 2020

- Herbert York, “The Advisors: Oppenheimer, Teller and the Superbomb”, 1976

- McGeorge Bundy, “Danger and Survival: Choices about the Bomb in the First Fifty Years”, 1988

- Martin Sherwin, “A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and its Legacies”, 2003

- Richard Polenberg, “In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer”, 2001

- Freeman Dyson, “Disturbing the Universe”, 1979

- Abraham Pais, “J. Robert Oppenheimer: A Life”, 2006