by Varun Gauri

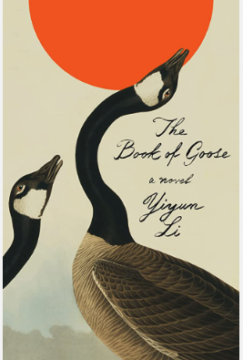

When Yiyun Li took questions about her new novel, The Book of Goose, at my local bookstore, someone said her new novel felt awfully dark. (I don’t remember the precise wording, though Yiyun might, as she sometimes offers people she has met briefly “a detailed account” of their encounter “out of mere mischief.”) Yiyun acknowledged the darkness, then offered an explanation — she was once a propagandist for the Chinese government, she was good at it, but now she hates propaganda, especially propaganda for life.

When Yiyun Li took questions about her new novel, The Book of Goose, at my local bookstore, someone said her new novel felt awfully dark. (I don’t remember the precise wording, though Yiyun might, as she sometimes offers people she has met briefly “a detailed account” of their encounter “out of mere mischief.”) Yiyun acknowledged the darkness, then offered an explanation — she was once a propagandist for the Chinese government, she was good at it, but now she hates propaganda, especially propaganda for life.

There was an audible gasp in the audience, then silence. I suspect many were asking themselves if they could manage without propaganda for life. In my case, I felt called out. What are A Christmas Carol, one of my favorite books, and the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, another favorite, but propaganda for life?

The Book of Goose is the story of two French farm girls, Agnès and Fabienne. Fabienne’s older sister died in childbirth, her father is a drunk, and her mother has passed away, meaning Fabienne has to tend the farm rather than attend school. Agnès’ older brother was badly wounded in the war, her sisters have gone and married, and her parents are narrow-minded and conventional. The girls, poor and lonely, already know the world is “full of nonsense.”

To amuse themselves, they start inventing macabre tales about dead children. Eventually, with the help of one of the novel’s many addled adults, they assemble the stories into a book. The book becomes a best seller, and Agnès, thrust into celebrity because her name is on the cover, goes to Paris and then London to be groomed for publishing stardom. The adults are incredulous, first that these farm girls could have written such a book, second that the girls show little interest in what the world offers them — the genteel feminine arts, marriage, conventional success. And all along, Agnès struggles with her secret — the true inventor of these stories, the true genius, is Fabienne, not her.

Fabienne is a force of nature. She climbs trees in a few seconds, holds her breath under water to tempt death, and throws cats up to roofs. She savages birds’ nests so she can watch eggs fall from heights. Farm animals always obey Fabienne’s command, and even the bees are afraid to sting her. Fabienne thinks most people are idiots, even, or especially, her friend Agnès, who is prone to “wishful thinking.” For instance, Agnès considers how unlikely it is that both Fabienne and her sister die in childbirth (not a spoiler, the reader learns this early), then feels like an idiot, because Fabienne would have scorned such naïveté.

A key question is why Agnès pretends to be the writer of their book while Fabienne refuses to acknowledge authorship, even though Fabienne is the storyteller and Agnès’ provides mere penmanship. Perhaps the answer is that Agnès does “not mind smiling at people, or carrying a basket for an old woman without her pestering me too much, or behaving obediently toward anyone” who has power over her, but Fabienne does mind all those things. Fabienne, it seems, is too proud and scornful, and too clear-eyed, to believe the world’s propaganda.

Late in the novel, when Agnès returns to her village, she finds that her parents respect her more, but their love remains meager. Agnès notes that her love for them is also meager and believes that’s how it should be. She says she is fortunate “not to have the desire, like some other children, to reciprocate insufficient love with an overabundance of wishful love, hoping that would make a difference.” Agnès learned that from her friend. It is easy to sympathize with Agnès here (and therefore with Fabienne) — does anyone receive all the love they deserve, and isn’t it tempting, and easier, to lie and say one got enough? Agnès pulls back from this kind of clarity, though, perhaps out of guilt, perhaps because the pain is too intense, and says, “I have only myself to blame when I cannot feel the love of others, my parents among them.”

Agnès may not love her parents, but she does love Fabienne. What does she see in Fabienne? Although she Agnès says childhood friendships are unexplainable, we can point to some reasons: Fabienne’s heart is like a gorgeous, hard crystal, which others cannot hurt or scathe; Fabienne feels the pain of the world intensely, and though tempted to turn her anger inward, instead chooses to avenge the nonsense life inflicts by leaving a mark on the world. Fabienne is a “genius,” or at least a “faux-prodigy,” though we don’t hear Fabienne’s stories and have to take Agnès at her word that her friend really can make the world less “hideous” and “tedious.”

Suppose Agnès had reciprocated her parents’ meager love by overcompensating, giving them a wishful overabundance. That’s what the world typically recommends — honor thy mother and father. That would have felt false, foolish, and infantilizing to Agnès. Fabienne would have called her an idiot. Agnès does not love the meager world; her American husband in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, seems sturdy enough, but hardly as compelling as Fabienne, their book, the games they invented at the graveyard in their childhood village. It seems Agnès is refusing propaganda for life on behalf of her friend’s propaganda for art. Maybe each of us needs to use whatever we can to fill, as Coetzee puts it, the “overlarge and empty human soul.”