by Deanna Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

I am no stranger to waking up in the middle of the night with a nameless feeling of dread. Like everyone else I know, I developed chronic insomnia around age 40, which was exacerbated by the “election” of Trump and the ongoing pillage of American democracy. And then perimenopause wreaked its havoc in the form of hormonal swings, night sweats, and troubled dreams. But this was different. This night—just over a month ago—I woke bolt upright out of a dead sleep, gasping for air, disoriented and terrified. I leapt out of bed and staggered to the bathroom, so dizzy I was bumping into walls. I found the toilet, closed the lid (an ongoing bone of contention in our household), and sank down with my head between my knees. I was dying. I knew, absolutely and with pure and stainless conviction, that I was dying. Dizziness washed over me, an intense feeling of disorientation, and I knew that it was my spirit separating from my body. I was swept with waves of grief. I haven’t written everything I want to write. My partner is in the next room and I don’t want to say goodbye yet. My family, my friends. Work to do, parties to throw. This toilet—it really needs to be cleaned. This is not dignified. I promise, Powers That Be, that from this moment forward I will no longer be cavalier about my life, if you just spare me now.

Suddenly a scrap of memory. A conviction that one is dying—that sounds familiar. I think … that can happen in panic attacks? Maybe I’m having a panic attack? But—how can this be? I have had panic disorder and intermittent generalized anxiety since I was 16, and have had hundreds of panic attacks in my life—never before did I become convinced that I was dying. For me the worst part of panic is the feeling of derealization, as if the world around me is fake and I am in a dream. (It’s very difficult to explain why this feeling is so horrifying to those who have never experienced it—you just have to trust me.) But that night in the bathroom I suddenly remembered that the sensation of dying is on the long list of panic attack symptoms, one I had always skipped over when reading about my disorder since it didn’t apply to me. And yet here we were.

Okay, okay. I might as well try the usual techniques I’ve perfected over the years. Deep breathing. Walking in circles while shaking my hands and feet. Splashing cold water on my face. Above all—not fighting it. Letting the feelings pass through me and trusting that I would come out the other side. It worked; I was released from the iron grip of terror; my soul returned to my body; I lived.

I did not sleep again that night. Read more »

Shilpa Gupta. Untitled 2009.

Shilpa Gupta. Untitled 2009.

If you were a medieval peasant in the year 1323 AD, would you have believed that slavery was morally permissible?

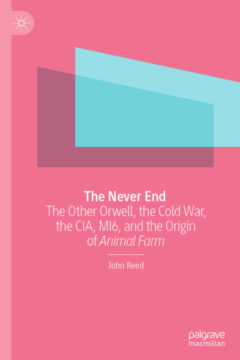

If you were a medieval peasant in the year 1323 AD, would you have believed that slavery was morally permissible? Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

“Martti Ahtisaari, ex-Finland president and Nobel peace laureate, dies aged 86” runs the headline of

“Martti Ahtisaari, ex-Finland president and Nobel peace laureate, dies aged 86” runs the headline of

I once wrote a political column for

I once wrote a political column for

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021.

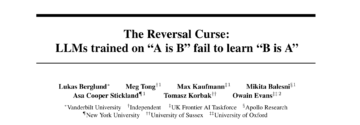

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021. bankruptcy were billing at $2,165 an hour ($595 for paralegals). Since then we learned:

bankruptcy were billing at $2,165 an hour ($595 for paralegals). Since then we learned: