by Joseph Shieber

When Theodor Adorno composed the aphorisms that formed the first section of Minima Moralia, he was living in exile in Los Angeles in the mid 1940s, a refugee from Nazi Germany. One of the most famous quotes by which Adorno is more widely known, “Wrong life cannot be lived rightly,” is from the 18th aphorism of Part I of the Minima Moralia, in an aphorism entitled “Asylum for the homeless.”

As is typical for many of the aphorisms, “Asylum for the homeless” begins with a pointed cultural criticism before broadening its focus to draw a wide-ranging conclusion about the possibility of a good life in late capitalism.

The pointed cultural criticism with which Adorno begins “Asylum for the homeless,” despite its title, doesn’t literally concern homelessness, but rather with the discomfort attendant with not feeling at home in one’s place of residence. He criticizes “traditional dwellings, in which we grew up,” because “every mark of comfort therein is paid for with the betrayal of cognition; every trace of security, with the stuffy community of interest of the family.” On the other hand, “functionalized [dwellings], constructed as a tabula rasa, are cases made by technical experts for philistines, or factory sites which have strayed into the sphere of consumption, without any relation to the dweller” (translation by Dennis Redmond, here).

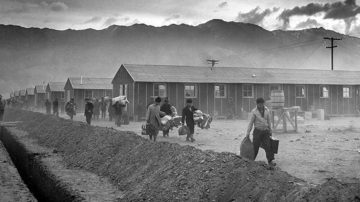

This emphasis on the contradictions inherent in attempting to feel at home might seem bizarre, considering the horrors facing those who were literally homeless at the time Adorno was writing: destitute refugees fleeing conflict, or the Japanese Americans forced into internment camps in southern California, not to mention Adorno’s co-religionists at death camps in central Europe. In contrast, during this period, Adorno himself lived in a lovely bungalow, “a quiet nice little house in Brentwood, not far, by the way, from Schönberg’s place,” as he described it in a letter to Virgil Thomson (for quotes from Adorno’s letters to Thomson, I am indebted to a blog post from James Schmidt’s blog, Persistent Enlightenment).

This isn’t to say that Adorno ignores the plight of those whose lives were destroyed by the conflagration of the early 1940s. He writes, “Things are worst of all, as always, for those who … live, if not exactly in slums, then in bungalows which tomorrow may already be thatched huts, trailers [in English in original], autos or camps, resting-places under the open sky.”

There is something a bit uncomfortable, however, about Adorno’s attempt to force the enormity of such tragedies into his culture-critical frame. This is perhaps most jarring in Adorno’s linking the advent of Hitler’s death camps to the disappearance of the good old family home: “The house is gone. The destruction of the European cities, as much as the labor and concentration camps, are merely the executors of what the immanent development of technics long ago decided for houses. These are good only to be thrown away, like old tin cans.”

However overwrought his musings on feeling at home, Adorno captures a deeper insight in the closing three sentences of “Asylum for the homeless”:

The trick consists of certifying and expressing the fact that private property no longer belongs to one person, in the sense that the abundance of consumer goods has become potentially so great, that no individual has the right to cling to the principle of their restriction; that nevertheless one must have property, if one does not wish to land in that dependence and privation, which perpetuates the blind continuation of the relations of ownership. But the thesis of this paradox leads to destruction, a loveless lack of attention for things, which necessarily turns against human beings too; and the antithesis is already, the moment one expresses it, an ideology for those who want to keep what is theirs with a bad conscience. There is no right life in the wrong one. (Again, translation by Dennis Redmond, here.)

The final line of the aphorism is more commonly known in English through the Jephcott translation, “Wrong life cannot be lived rightly.” The German is, “Es gibt kein richtiges leben im falschen.” What Jephcott’s translation misses, and what Redmond’s does a better job of capturing, is that Adorno is suggesting that systemic forces can render it impossible for individuals to live rightly.

The previous sentences illustrate this general, systemic point using the relation of individuals to property. In a phrase that the Liberty Fund could love, Adorno suggests that the claim that “private property no longer belongs to one person … necessarily turns against human beings too.” The opposing claim, that “one must have property” is little more than “an ideology for those who want to keep what is theirs with a bad conscience.”

Adorno’s closing thoughts, however, seem better at capturing the feeling of living in consumerist capitalism than at offering deep ethical or moral insight. It is true that feelings often take on an all-or-nothing perspective, but philosophers can and should do better.

First, there is the fact that there is room between the two extremes, “private property no longer belongs to one person,” on the one hand, and everyone keeps “what is theirs,” on the other.

Second, even for those of a tragic frame of mind when considering the inevitable forces shaping political economy, there is room to see that a diagnosis according to which no act is right is not an apt framework for ethical evaluation. Even if no act is right, there should still be space to same that some acts are better than others. Documenting the American mistreatment of citizens of Japanese descent, as Dorothea Lange did in a series of photographs that were seized by the US Government, is a better act than serving as a camp guard at Manzanar.

Where feelings often have trouble is with ambiguity or subtlety. Precisely in such spaces, however, is where philosophy ought to thrive. “Asylum for the homeless” is one example in which Adorno demonstrates that, however at home he might be in expressing the feeling of despair associated with life in late capitalism, there is a danger that, as philosophy, his work leaves us homeless.