by Richard Farr

From our Men’s Modern Living correspondent:

I know, I know. You’re thinking: “Don’t even start. I saw two dozen spittle-flecked jeremiads on this topic last week alone, including that 17,000-word essay by Randomdude in one of those illustrated monthly magazines they have at my club. Substack? It was called something like Apocalypse Now: Why You Should Be Running Around Shrieking With Your Hands In The Air. To be honest, I was forced to abandon it after a few paragraphs when I started to have painful attacks of ennui, déjà vu, and prèt-à-manger.”

No shame there! In this brave new world of moving fast and breaking the bleeding edge off things, not every writer can be hypnotically persuasive, even when the very fate of Mankind is at stake. But you need to pay attention now, because what the world’s most august technical gentlebros are saying about these latest developments is NOT HYSTERIA.

On the contrary, the new “automated calculating engines” are going to change everything, either in ways that we can’t possibly predict, but should be terrified out of our wits by, or else in ways we can predict and already have predicted in excruciating detail, and should be terrified out of our wits by. I mean it, and I’m not exaggerating: when these machines go mainstream, ka-poufff. Literally. In less time that it takes for you to say to your housekeeper “Alexa, order me three of them and then send two back because what was I thinking?” the whole world will have become unrecognizable, the way toast does when you put mashed avocado on top. Read more »

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

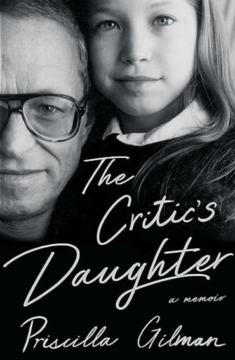

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

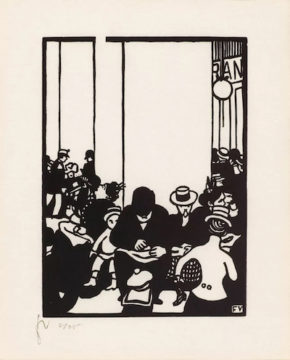

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

You don’t have to fuck me. Or give me any money. You don’t have to shave your head or adopt a peculiar diet or wear an ugly smock or come live in my compound among fellow cult members. You don’t even have to believe in anything.

You don’t have to fuck me. Or give me any money. You don’t have to shave your head or adopt a peculiar diet or wear an ugly smock or come live in my compound among fellow cult members. You don’t even have to believe in anything. Sughra Raza. At Totem Farm, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. At Totem Farm, April 2021.