by Carol A Westbrook

Dementia refers to progressive, irreversible cognitive impairment usually seen in the elderly. The clinical findings of dementia almost always include some degree of memory impairment. We didn’t know much about how memories were formed in the brain until 1953, when the now-famous patient named Henry Molaison, HM, had removal of an area in the temporal lobe of his brain called the “hippocampus” the operations successfully prevented seizures, but unfortunately HM also lost the ability to form new memories of events, and his recollection of anything that happened in the preceding eleven years was severely impaired. Other types of memories such as learning physical skills were not affected. This was the first step in learning about how and where memories are formed in the human brain.

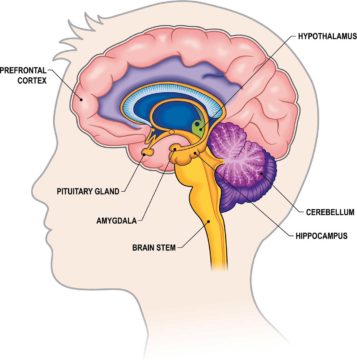

We now know that the hippocampus plays an important part in the formation of new memories by the physical interaction and modification of neurons, and it also processes short -term memories into long-term memories, which are then stored in the frontal cortex. Specific brain structures have other specific tasks in memory development, (see figure 2) such as the amygdala, the area of the brain which adds emotional pertinence to memories such as fear, pleasure or pain, whereas physical skills and movement are dependent on the cerebellum. We are beginning to understand how and why specific brain lesions can lead to different forms of dementia. Read more »

“Martti Ahtisaari, ex-Finland president and Nobel peace laureate, dies aged 86” runs the headline of

“Martti Ahtisaari, ex-Finland president and Nobel peace laureate, dies aged 86” runs the headline of

I once wrote a political column for

I once wrote a political column for

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021. bankruptcy were billing at $2,165 an hour ($595 for paralegals). Since then we learned:

bankruptcy were billing at $2,165 an hour ($595 for paralegals). Since then we learned:

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written.

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written. Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.

Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club