by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

It was Tetsuya’s idea to start calligraphy lessons.

I had wanted to study Aikido. But according to Tetsuya, I was already dangerous enough. “And, anyway,” he said, “You know what Confucius said: the pen is mightier than the sword.”

“Confucius definitely did not say that.” I rolled my eyes.

His idea, however, grew on me. So, a few weeks later, the two of us found ourselves standing in front of a tidy, two-story home in suburban Hachioji. Located at the end of the Keio line, Hachioji is as far west as you can travel in Tokyo without arriving in Kanagawa Prefecture.

A few days before our first class, Tetsuya had a long consultation by phone with the teacher, Yufu-sensei, and it had been decided that I should be placed in the class with grammar school students, since at that point I only knew the kanji through 5th grade. When I tried to resist being in a class of kids, Tetsuya told me to get rid of my pride immediately or this won’t end well for you.

Anyway, he said, he would sit in the class with me to make sure I was okay. With that promise, I felt confident. Tetsuya had beautiful handwriting. He was already proficient at writing with brush and ink, though he told me that all he could manage was kaisho, the “square style” or “standard style.” Kaisho is the first style that shodō practitioners usually learn and master, he said.

The lessons were held on the second floor of the teacher’s home. A hush fell over the room as we entered. Not only were adults joining the kids’ class but one of those adults was not Japanese. Definitely not Japanese.

The children just stared in disbelief.

In addition to being highly tactile, writing with sumi ink activates one’s sense of smell. Maybe because our sense of smell is connected to memory, even now I can vividly recall my first brushstrokes. While the rest has mainly faded, those first characters remain shimmering in my mind.

Except that Yufu-sensei would not permit me to write Chinese characters at first. He had me starting with hiragana, the phonetic system that functions like an alphabet. This delighted the children since they had all fully mastered hiragana by first grade.

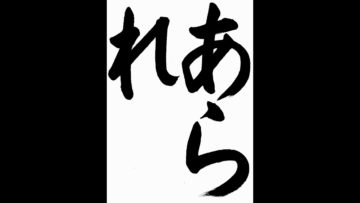

My first calligraphy would be three hiragana characters: あられ。Arare, which means “hail”

“Ganbatte-ne!” (Do your best!) The children shouted encouragement as I walked back to my place and sank into my chair.

2.

The great Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish suggested that cities are smells:

Acre is the smell of iodine and spices, he said, And Haifa is the smell of pine and wrinkled sheets.

For me, Tokyo was always the smell of sushi vinegar and tatami mats. But mostly it was the smell of ink.

A little like moth balls and a little like patchouli, it has a very distinctive smell– and like the characters themselves, sumi came to Japan by way of China, where it has been made for over 2,000 years with animal glue and pine soot. And with incense used to cut the smell.

For my early lessons, I used ready-made ink from a bottle. Yufu-sensei would pour a small dollop into the hallow part of my student inkstone. The plain dark inkstone was part of my student starter set, which was a far cry from the exquisitely carved, luminous purple-red duan inkstones I had drooled over in Hong Kong. In addition, the set also included two brushes, a paperweight, a felt writing surface, a water dropper, and calligraphy paper –about three-hundred sheets.

And so, in the beginning, I would not grind my own ink, by rubbing an inkstick into water droplets in the inkstone. Sensei did not want to overwhelm me, and suggested I continue with the ready-made ink, though he did tell me that the preparation of the ink is perhaps the best part of the practice since it calms the mind and stills the heart.

3.

あられ。Arare.

As I dipped my brush in the inkwell for the very first time, Tetsuya whispered for me to be careful.

Calligraphy is a performance art: the moment the ink touches the highly-absorbent rice paper, there is no going back. That paper is the most unforgiving surface and calligraphy does not allow for re-writes or revisions.

That is why it is seen as an expression of a person’s vital energy, “ki” or “chi”.

Looking over at Tetsuya frowning, I realized every eye in the room was on my brush—even sensei’s!

And so I wrote the first hiragana character: あ

“A”

Even now, it’s my favorite hiragana character.

Sensei had written the three hiragana making the word a-ra-re on a separate piece of paper. This model example is known as “o-te-hon.” お手本

Nowadays, people are quick to disparage the focus on rote memorization that one finds in East Asian education systems, but I think it helps to keep in mind, that the memorization of facts is always only the first stage.

Many never make it past this stage, of course. But, the internalization of models and memorized knowledge ideally leads to imaginative and creative conclusions. So that, for example, even today in Japan, the rules and conventions of writing calligraphy are rigorously taught in school. If a character is not written according to the rules, it is marked “wrong.” This rule is upheld much further than elementary school.

The same can be said of other traditional subjects, from the “kata” in martial arts to recitation of poetry, vast amounts of knowledge are bodily memorized, learnt by heart, taking years. This, however, was never the final goal. My calligraphy teacher used to tell us that the breaking of calligraphic rules are only beautiful or interesting in those people who have mastered the rules. Never the other way around.

Like Picasso would not have been interesting if he hadn’t first took the Academy by storm. This was something my tea ceremony teacher would say again and again when I complained about the endless things I was being made to memorize.

This stress on internalization of exemplary models has a fundamentally different approach than modern methods of learning, where knowledge is imparted more systematically. In later years I worked translating for a Japanese philosopher, whose own work was concerned with traditional styles of learning in East Asia. He thought that Western model of systematized knowledge was based on Cartesian mind-body dualism. According to him, in the pre-modern Japanese world, there was no division between mind and body in the Japanese language as words for body like “mi” 身 and “karada” 身体 encompassed both mind and body. For that reason, he explained, traditional Japanese arts, like dancing and music, were taught by emulation. There was no breaking down of the whole into parts, not real systematization, but rather the pupil just copied over and over again the teachers example.

This was true of calligraphy and tea in Japan—but it was also true of my dance lessons in Indonesia. The teacher stood in front of us—no mirrors—and showed us what a movement was supposed to look like. We were to keep our eyes on her –there were no mirrors– so our eyes would imbibe the correct manner of moving as we tried to emulate her.

4.

Arare.

I am guessing my calligraphy lessons first began in early winter since “arare” –which means hail– is a winter term in poetry.

時々に霰となつて風強し ―正岡子規

Now and again

The wind so strong

Turns to hail

–Masaoka Shiki

The kanji hail 霰 is written phonetically in hiragana as あられ.

5.

5.

Every year, our calligraphy teacher would organize a pilgrimage to the Palace Museum in Taipei so his top students (not me) could stand in front of the greatest works of Chinese calligraphy.

Those trained in the art of writing in brush and ink are not only able to admire the work for its formal aesthetic qualities but are also able to feel what it felt like to create it.

Because people learn to strictly follow stroke order (except for artistic geniuses and other creatives), when you look at a work of calligraphy, you can physically experience the speed and pressure of the brush, take pleasure in the flourishes and full stops. You breathe along, as if you were writing it yourself. It is like watching a routine in ballet that you yourself know how to dance.

For example, in writing the “あ” in あられ:

I take in a deep breath, noticing the air fill my belly. This place in the lower abdomen, called tanden, is believed to be the seat of a person’s vital forces. If a person’s mental preparation is good, this vital force or energy (called ki 氣) can be discerned in the finished calligraphy. Called bokki— the kanji BOKU (墨 ink) and KI (氣 energy)– it is the manifestation of a person’s “ki-ai” (気合). That is, your spirit in the ink.

The eight types of brushstrokes are used when writing the character “eternal” (see left). Unfortunately, I was starting with hiragana not kanji. But most students begin writing “eternal.”

I write the first horizontal stroke. From left to write, I end the horizontal stroke with a conscious down-pressing of the brush. This is all in the wrist. The written effect reminds me of the knob-like end of a human bone.

The vertical is just straight down, top to bottom, nothing fancy.

Then comes the fun part, the loop. Starting at the top, close to the horizontal line, I carry the brush in a loop ending below the bottom of the vertical. It is not a dot ending like in the vertical and horizontal but pressure is decreased on the brush so the ink fades into white.

I breath. Looking around the room, everyone looks relieved.

6.

6.

French historian Jacques Gernet, in his History of Chinese Civilization, characterized China as a “wise man”–in contrast to “holy man”—culture, such as those found in India or the Holy Land. While this characteristic can be traced all the way to ancient Zhou Dynasty times, with Confucius, the significant role given to self-cultivated wisdom came to take center stage.

Because the enlightened kings of antiquity were not just kings but were revered as “sage-kings,” emperors also came to find it in their political interests to cultivate themselves, in part through the patronage of the arts and knowledge of the classics, in order to demonstrate their wisdom, in accordance with the “Way of the Ancient Kings.” Not only the collecting, but the practice of art also became one of the essential moral pursuits of a gentleman– whether he be a king or scholar.

In Jing Tsu’s tour de force new book, Kingdom of Characters, the Language Revolution that Made China Modern, she begins her prologue suggesting that in no other country would heads of states kick off official ceremonies with displays of cultural prowess. She was referring to modern leaders of China from Mao to Hu Jintao’s public displays of expert penmanship.

Even now, Mao’s calligraphy adorns the masthead of the People’s Daily. In Richard Curt Kraus’ fantastic book, Brushes with Power: Modern Politics and the Chinese Art of Calligraphy, he explores how calligraphy stands as a metaphor for the elite culture of imperial China and this grandiose legacy that Chinese in the late 20th century have received with ambivalence. He begins his book, also with Mao’s calligraphy, which he finds on a pair of nail clippers. “Serve the People” it says, in Mao’s easily recognizable handwriting.

I agree with Jing Tsu, that it is hard to imagine a modern American or European president displaying their own cultural know-how on a state visit or official ceremony, like in China. But, I would argue it is quite common to see in Japan, where expert displays of calligraphy, art connoisseurship, the martial arts and tea are prized. East Asia has not embraced the anti-intellectualism found at home in the U.S., where most politicians would prefer to keep their literati side on the down low. If they have one, that is. Obama has been unique to be so vocal about his rich and wide-ranging reading habits.

7.

As winter turned to spring, I next practiced the kanji for spring rain: harusame 春雨

I would keep at my calligraphy lessons for many years. It is hard to quit things in Japan since one enters into a relationship with the teacher and fellow students. It becomes an obligation. But that is not a bad thing.

When I was hired to work at Hitachi, my boss told me they committed to hiring me the moment they saw my Japanese handwriting.

“We knew you would be hardworking.”

It is true, I worked hard and loved it.

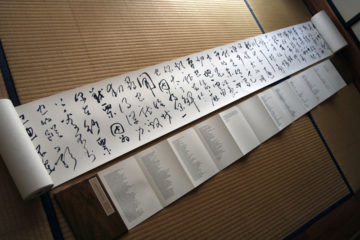

Even after moving to Tochigi, a hundred miles north of Tokyo, Yufu-sensei, who was so kind to me, would send my lessons by post. Opening the A4 size envelopes in my new home, the fragrance of sumi was overpowering. Sometimes, the envelopes would contain the model calligraphy for the week in his impossibly graceful writing.

Sometimes it would be my own writing returned with his corrections written in red ink. Overlaying mine they traced a way to write the letters that were more beautiful, more correct, more perfect.

++

My substack on Japan: Dreaming in Japanese (short weekly blasts on Japan)

November 3QD post: Calligraphy in the Garden

Gulf Coast Journal: For the Love of Oranges

Leanne Ogasawara

Michael Cherney’s Excerpt from Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (2012).