by Usha Alexander

[This is the sixteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing.

Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing.

Of course, it is a normal dynamic of evolution that one species occasionally will outcompete another and drive it toward extinction. But for most of their time on Earth, human beings were not having an outsized, annihilating effect on the life around them, rather than co-evolving with it. That evolution was at least as much cultural as it was a matter of flesh. What people consumed, how they obtained it, and how quickly they used it up has always played a role in the stability and evolution of any ecosystem of which humans were a part. How fast human populations grew, how they sheltered, what they trampled and destroyed or nourished and promoted—all of this affected their environment. Naturally, their interactions with the environment were always driven by what they wanted. And what people want is intimately driven by what they believe, as in the stories they tell themselves. One thing we can safely presume: those who understood their own social continuity as contingent upon that of their environment weren’t telling the same stories we tell today.

Humans began to have a more devastating effect on their local environments when they finally spilled out of Africa and began spreading across the globe. To begin with, those who left Africa also left behind most of the disease pathogens and parasites that had co-evolved with them1, which surely aided their own survival rates. Humans were also elite predators, who hunted and foraged like no other animals elsewhere. Population growth and colonization are animal drives that must be met by contravening forces of predation, disease, or resource scarcity to maintain balance within an ecosystem, but outside their native range humans could overwhelm many of these factors. And the new worlds they encountered at every step surely changed their stories—and their societies—in profound ways. Indeed, one might conjecture that our destiny to conquer the Earth was fully sealed by the time our anatomically modern ancestors marched into the cold, dry mid-latitudes of Pleistocene Australia, where their presence hastened the demise of the continent’s unique megafauna. What stories did those pioneers tell of outsmarting the towering marsupial, diprotodon? Of overpowering the massive lizard, megalania? Of sharing such tremendous feasts?

But that wouldn’t be the whole story. For the drive toward social cohesion and continuity is surely at least as strong among humans as the drive toward novelty and domination. Collective survival mattered to foraging societies, and the lessons of successful ecological balance—failures of which could lead to famine and community dispersal—were as old as time. So as those astounding animals disappeared from the Australian landscape, what stories were inspired by their loss2? We don’t know the effect local extinctions had on individual societies tens of thousands of years ago, but witnessing the dramatic demise of megafauna, forests, grasslands, or any other features on which they depended must have made a deep impression—if not caused outright disruption. Even as various groups struggled, innovated, and experimented to find new balance in new landscapes and climates across the planet—even as recently as mid-Holocene times—such profound lessons were certainly not lost on everyone. And they need not be lost upon us now.

Crucibles of Experimentation

It might be instructive in this regard to look at stories from the peopling of the Pacific, which provides countless illustrations of how different societies managed social cohesion and continuity. Or didn’t. Small, remote islands are unforgiving crucibles for human social and material experimentation: Through trial and error, the exercise of wisdom, and the guidance of ancient lore, a colonizing people, especially those encountering a true terra nullius, must fashion a way of life that brings them into sustainable balance with their narrowly circumscribed ecosystem. Failing this, they’ll eventually be forced to abandon their island—or perish entirely. These are the only possible outcomes. And all three fates were known to befall different groups who braved this vast, watery span of the planet.

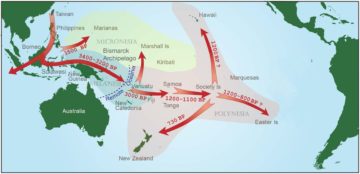

The peopling of the Pacific might be said to have begun about five-thousand years ago, when the first families set off in canoes from Formosa Island (modern-day Taiwan) along with their dogs, chickens, pigs, rice, and other crops: the core of their subsistence economy. Hailing from various parts of the island, they spoke a variety of different Austronesian languages. And as they went, they mixed and mingled with many other peoples: the indigenes of Luzon and other Philippine islands, the Southeast Asian mainland, the Indonesian islands, as well as New Guinea and other Melanesian islands. Their descendants then carried onward the indigenous horticultural knowledge and foods from these tropical regions—including coconuts, taro, and bananas—alongside their ever-diversifying Austronesian languages. Over generations, these seafarers also perfected their ocean-going craft and learned to read the waves, winds, and stars with breathtaking acuity. Fewer than five-thousand years after departing Formosa, Austronesian-speaking families had sailed and settled as far west as Madagascar; eastward, they had dispersed among the tiny, North Pacific atolls of Micronesia and the scattered volcanic and coral islands dotting the breadth of the Pacific Ocean, from Hawaii to Rapa Nui (Easter Island) to Aotearoa (New Zealand)—the Polynesian Triangle3. And thus nearly every last, far-flung sandy shore of the Pacific received its first human footfall before Europe had even begun its own Age of Exploration.

Each island was of course unique and those who remained to colonize it had to adapt in order to thrive. Over the millennia, many of these Austronesian colonies endured periods of extreme hardship as they faced droughts and hurricanes, as they made war, were infested by rats, or despoiled their delimited and ecologically fragile landscapes. Sometimes they failed to overcome these trials and found no sustainable balance. But often, they succeeded. Their ancestors had long proven themselves masters of adaptation and invention, and most of these new island societies thrived, evolving unique and complex civilizations, social systems, and inter-island relationships, many of which persist up to the present day. In light of how incapable we often presume people are of achieving it, I find it especially humbling to think about those who mastered continuity.

Fortune, Misfortune, and Adaptation

Two of the astonishing Polynesian success stories come from the islands of Tikopia and Anuta. Tikopia is one of the smallest and most remote inhabited specks of the Solomons archipelago. With a footprint of less than two square miles, the island is crowned by emerald peaks ruggedly splayed above a large crater lake. The nearest larger island—Vanua Lava, still rather small at one-hundred and twenty square miles—is a week’s journey by canoe, so the Tikopia have maintained only infrequent and sporadic contact with the outside world, even up to the present day. Nevertheless, their jungle-draped spot of land has been continuously inhabited by the descendants of various Polynesian and Melanesian groups who independently arrived from many different islands, beginning at least three-thousand years ago. While the migrants’ early encounters with one another might not have been entirely peaceful, they eventually blended into a single society, jointly governed by the leaders (ariki) of its four clans, whose clansfolk are distributed in mixed and freely intermarrying settlements across the lowlands4.

Two of the astonishing Polynesian success stories come from the islands of Tikopia and Anuta. Tikopia is one of the smallest and most remote inhabited specks of the Solomons archipelago. With a footprint of less than two square miles, the island is crowned by emerald peaks ruggedly splayed above a large crater lake. The nearest larger island—Vanua Lava, still rather small at one-hundred and twenty square miles—is a week’s journey by canoe, so the Tikopia have maintained only infrequent and sporadic contact with the outside world, even up to the present day. Nevertheless, their jungle-draped spot of land has been continuously inhabited by the descendants of various Polynesian and Melanesian groups who independently arrived from many different islands, beginning at least three-thousand years ago. While the migrants’ early encounters with one another might not have been entirely peaceful, they eventually blended into a single society, jointly governed by the leaders (ariki) of its four clans, whose clansfolk are distributed in mixed and freely intermarrying settlements across the lowlands4.

Even smaller and more remote than Tikopia, Anuta lies seventy miles further to the southeast, with a footprint just shy of half a square mile. The first people to settle on Anuta, some two-thousand years ago, abandoned it within a few generations, after a devastating hurricane storm surge inundated the land. Over a thousand years passed before new colonists would try again. These were the ancestors of Anuta’s present inhabitants, who arrived at least six-hundred years ago, in a unique yet broadly parallel story to Tikopia. These two microcosms, Tikopia and Anuta, have kept friendly relations for centuries although, remaining yet so remote from one another, they’ve each had to maintain material self-sufficiency. Some decades ago, both were incorporated into the Solomon Islands nation, though this has had little material bearing on the everyday lives of their people. While the culture and history of Tikopia is better documented, both cultures are organized along similar principles and have managed centuries of continuity within limited resources.

Tikopia society is definitively patriarchal, albeit not of the more extreme variety. Patrilineages are ranked, though far less so than in many other Polynesian societies, with the ariki of each clan assigned through male primogeniture. Among the Tikopia, an ariki is awarded great formal respect but commands no coercive power to enforce behaviors on others. Rights to particular parcels of land for building houses and growing food gardens, as well as to access certain lake-fishing spots, are inherited and held by the patriarchs of each family. Highly ranked families often have more or better land holdings, so they may be “wealthier” than others. Everyone—even an ariki—works in the gardens and catches fish for their household, women walking along the reef with hand-nets and men in the deep from canoes. Everyone takes part in cooking. Everyone participates in childcare. While there is an expectation that each family is self-sufficient in its food production, networks of relationship and obligation ensure that no one is ever without food, shelter, or any basic necessities—an arrangement they refer to as aropa—so differences in landholdings do not imply want or competition for subsistence, and thus don’t systematically enable control over others through enforced scarcity, as we see in capitalist systems. Tikopia has no army or police force, courthouse or jailhouse. One ariki describes his job as governing the people on the island to “see they have no quarreling about the land. They must all share.”

Though small, both Tikopia and Anuta islands are blessed with freshwater springs, volcanic soils, flocks of birds, and encircling reefs. However, they do experience periodic drought and lie in a very active hurricane zone—Tikopia has historically been struck by hurricanes about once a decade (it now happens every other year). Hurricanes and droughts present existential hardship, as trees and houses are sheared away by winds, gardens wither or get washed away, water sources are contaminated or run low. The island’s geography and ecology, too, have undergone changes over the last three-thousand years, some due to human activity and some for reasons beyond human effects. For instance, the large crater lake of Tikopia, rich with fish and supplying suitable habitats for growing sago palm and other foods, has only been a freshwater lake for the past four hundred years; prior to that, it was a saltwater bay5. These are the sorts of changes, challenges, and occasional opportunities to which the Tikopia have steadily adjusted. And over the millennia, their lifestyle choices have changed a great deal. For instance, the Tikopia once had a pottery tradition. But after almost a thousand years of living on the island, they stopped making their own pottery and began to import it from other islands; a few generations later, they altogether abandoned the use of pottery on their island. Archaeology also attests that the islanders once regularly consumed fruit bats and eels, but they later stopped including these in their diet. It’s unknown what drove these changes. Perhaps they ran out of suitable clay to make pots. Maybe they noticed their gardens grew stunted when decimated bat populations dropped less of that wondrous fertilizer, guano. Or they discovered some other troubling change on their island correlated with those older practices. But the culture adapted. About four hundred years ago, the Tikopia decided to enjoy their last meals of pork—an ancient food staple among nearly all Austronesian cultures—and thereafter to banish pigs from their island, because the pigs were damaging their gardens. While pigs must always have damaged their gardens, one wonders whether around 1600 CE the human population had grown too high or depleted the island to the point that competing with pigs for food was no longer tenable. What’s interesting is their solution: rather than competing for increasingly rare pork, or allowing only a few to have it, they decided instead to jointly bear the cost of sacrificing pork and gain the benefit of more productive gardening.

Overall, the islanders’ consumption of animals declined over the millennia; meanwhile they were continually adopting new plant foods from other islands, such as Canarium nuts and manioc and new varieties of bananas and coconuts, learning how to incorporate them into their island’s thriving jungle. The Tikopia identify over one-hundred and fifty plant species on their island, nearly all of which they have a use for, including bamboo, pandanus, and red turmeric used for material or ritual purposes. They build their houses with low roofs to better withstand hurricanes; they preserve food underground that can be called upon in an emergency, even after years; they maintain and repair rare or resource-intensive tools, like canoes, so they might even last for decades6. Such adaptations were shaped by a close awareness of their cultural and natural constraints.

Overall, the islanders’ consumption of animals declined over the millennia; meanwhile they were continually adopting new plant foods from other islands, such as Canarium nuts and manioc and new varieties of bananas and coconuts, learning how to incorporate them into their island’s thriving jungle. The Tikopia identify over one-hundred and fifty plant species on their island, nearly all of which they have a use for, including bamboo, pandanus, and red turmeric used for material or ritual purposes. They build their houses with low roofs to better withstand hurricanes; they preserve food underground that can be called upon in an emergency, even after years; they maintain and repair rare or resource-intensive tools, like canoes, so they might even last for decades6. Such adaptations were shaped by a close awareness of their cultural and natural constraints.

Continuity and Cooperative Restraint

Notably, the Tikopia also consciously decided that some technologies used elsewhere in the world weren’t well suited to the preservation of their island or way of life. Each novel technology was evaluated on its own merits and risks. For instance, when passing whalers in the eighteenth century introduced them to metal knives and axes, they readily mastered their use and care. On the other hand, they long resisted more intensive farming methods, concrete buildings, and participation in commercial activities, which they reckoned might pose a danger to their ultimate wellbeing.

Perhaps the most difficult adaptation, however, was population control. At some point, the Tikopia figured out that their island could only reliably sustain just over a thousand people. On Anuta, the carrying capacity was adjudged closer to a couple hundred. Exceeding these limits by too much endangered everyone, especially in hurricane or drought conditions; unchecked growth ultimately worked against social cohesion and continuity. So population growth on the island was historically stalled by various means. As is typical in non-industrial societies, Tikopia’s child mortality due to illness or accident was also high. But when the population faced severe food stress in times of drought or hurricane, men were known to sacrifice themselves, setting out on rafts to face a quick death at sea rather than a slow death by starvation. The Tikopia also recall two wars in which a portion of the population was forcibly expelled from the island. But the most regular form of population control was the everyday practice of coitus interruptus.

While some people had three or four children, others had none of their own. Some remained childless by choice. Others were pressured into abstaining from reproduction, with the entreaties falling most heavily upon a patriarch’s younger brothers, whose marriages would divide family landholdings7. On Tikopia, unmarried individuals had always been free to enjoy sex amongst themselves, so long as their escapades didn’t result in pregnancy. But should a couple decide to have a child, they were expected to marry8; conversely, children were never to be born out of wedlock. In practice, this generally meant that one didn’t marry unless she or he intended to have a child, which not everyone could do. One’s family wealth and birth order played a substantial role in enabling an individual to choose to procreate. A woman finding herself with an unwanted pregnancy might attempt to induce abortion by pressing hot rocks against her abdomen but, even when this crude method did actually work, it sometimes resulted in her own death as well. Safer and more reliable was infanticide at birth. For a married woman, the decision and the act were left to her husband’s discretion: if he felt he didn’t have the means to feed the child—usually because the couple already had three or four children—he stated as much and immediately placed the newborn face-down on their mat, causing it to quickly asphyxiate.

As Christianity eventually took hold among the island’s populace, these practices were slowly phased out of the Tikopia way of life. Anglican missionaries had persistently pursued the souls of Tikopia for decades before their efforts found purchase in the early twentieth century; some decades after that, their religion was finally accepted by all the islanders. Engaged there to teach, rather than to learn, the missionaries neither appreciated the natural limits of the island’s resources nor could abide the Tikopia practices of sex without marriage and birth control. The missionaries and, later, Tikopia’s own converts to Christianity, put increasing pressure on the islanders to amend these ways. Over the past century, the Tikopia population has swelled. Today most Tikopia live on other islands within the Solomons, while the population on their home island remains just below thirteen-hundred souls. As those living in the capital, Honiara, are more subject to the economic pressures and opportunities of the globalizing world, their close ties with their home island introduce more foreign materials and ideas at an increasing rate today.

The traditional population control measures of Tikopia were harsh. But not, I think, more so than the fate of other Pacific islanders who did not succeed in finding a sustainable balance with their ecosystem, who suffered societal disintegration, starvation, and measures most extreme (to be addressed in my next essay). What’s striking about the Tikopia isn’t only that they created a civilization that has persisted for three-thousand years, but how they managed it. Their story tells of unceasing innovations and adjustments to changing conditions. They faced limits to their growth and the consequences of their material exploitation, as we do today. But rather than calling for deeper extraction and resource use, their innovations involved cultural adaptations that required embracing prudent limits—of consumption, production, reproduction. Rather than forcing their environment to produce more or innovating ways to temporarily hide the damages caused by their extraction or consumption, the Tikopia adjusted their expectations and practices instead. At some point, they concluded that they could do without pottery, inventing less resource-intensive modes of cooking and carrying. Likewise, they determined that bats and eels had special powers and must not be eaten. They figured out that they could not compete with pigs, so pork was struck from the menu. They changed their stories, their needs, their culture. Social cohesion and continuity were apparently more important to them than the limitless fulfillment of individual desires.

It can hardly escape our notice, too, that Tikopia society is built on broad cooperation, rather than competition; they essentially avoid the classic “tragedy of the commons” by sharing the wealth and the costs of its production, so there’s no individual incentive to overexploit and hoard the benefits. Tikopia social rankings are also relatively flat and lack strong institutional structures granting one individual or group coercive power over others. In fact, these features are common to many societies with deep continuity, including Indigenous peoples in Australia as well as in Central and South Africa, societies that systematically elude what political scientist William Ophuls has called the “immoderate greatness” to which so many nations feel entitled or compelled. Of course, those who avoid such “greatness” surely wouldn’t see that as their goal; they might simply want to preserve their high levels of individual autonomy and maintain the resources that sustain them. All of these cultural characteristics as well as the manner of Tikopia responses to environmental change stand in stark contrast to our own stories of growth and dominion over Nature, and our obsession with individual wealth, which we seem loathe to abandon.

It can hardly escape our notice, too, that Tikopia society is built on broad cooperation, rather than competition; they essentially avoid the classic “tragedy of the commons” by sharing the wealth and the costs of its production, so there’s no individual incentive to overexploit and hoard the benefits. Tikopia social rankings are also relatively flat and lack strong institutional structures granting one individual or group coercive power over others. In fact, these features are common to many societies with deep continuity, including Indigenous peoples in Australia as well as in Central and South Africa, societies that systematically elude what political scientist William Ophuls has called the “immoderate greatness” to which so many nations feel entitled or compelled. Of course, those who avoid such “greatness” surely wouldn’t see that as their goal; they might simply want to preserve their high levels of individual autonomy and maintain the resources that sustain them. All of these cultural characteristics as well as the manner of Tikopia responses to environmental change stand in stark contrast to our own stories of growth and dominion over Nature, and our obsession with individual wealth, which we seem loathe to abandon.

Enough Is Enough

Such human stories make me doubt that the ongoing mass extinction caused by human ecological overshoot was an inevitable consequence of human nature. What we know about human diversity and ingenuity, sensitivity and survival sense, suggests we could have chosen to stop it—each group at least in its own locale—as some, like the Tikopia and Anuta, did manage to do. Different societies have all along made different choices in how to structure their social and material worlds, how to care for one another, and how to adapt to the changing land, leading to vastly different outcomes. The Tikopia and Anuta may be a small populations, but they reveal the possibility of making collective choices that promote cooperation and continuity in balance with one’s local ecosystem.

Such human stories make me doubt that the ongoing mass extinction caused by human ecological overshoot was an inevitable consequence of human nature. What we know about human diversity and ingenuity, sensitivity and survival sense, suggests we could have chosen to stop it—each group at least in its own locale—as some, like the Tikopia and Anuta, did manage to do. Different societies have all along made different choices in how to structure their social and material worlds, how to care for one another, and how to adapt to the changing land, leading to vastly different outcomes. The Tikopia and Anuta may be a small populations, but they reveal the possibility of making collective choices that promote cooperation and continuity in balance with one’s local ecosystem.

Long-term social and cultural continuity does not happen by accident. Nor is it conjured by the Invisible Hand of the Market. Achieving it requires consciousness and cooperative cultural restraint. It requires stories that put us in a different relationship to our world and to each other, such that we rediscover meaning as socially and materially embedded creatures on a finite planet, and remember the sense of enough. Enough stuff. Enough power. Enough material desire and empty satiation. It means accepting that the Second Law of Thermodynamics appertains to us all, even the wealthiest and most technologically “advanced.” People, societies, do have the capacity to understand and undertake such choices. While our global civilization does not today elevate the stories that enable this way of constructing civil society—indeed, our common ideas of what civilization even means frankly excludes this possibility—it seems important to remember that these outcomes do lie well within the scope of ordinary human potential, maybe the hope of a future version of civilization. For our present experiment with civilization is likely not the last.

[Part 17: Stories of Collapse. All essays in this series can be read here.]

Notes:

1 Over many millennia, most of those ancient diseases (e.g., malaria, schistosomiasis) would eventually follow human migrations out of Africa. At the same time, new ones (e.g., Hansen’s disease (leprosy), Chagas disease) would also evolve to infect human hosts in their new environments. When people began living in dense, settled communities, particularly in close proximity with domesticated animals, more new pathogens (e.g., bubonic plague, smallpox, avian flu) would explode across the human landscape, as microbes found plenty of opportunity and fleshly fuel to jump species’ barriers and rapidly spread. And so it goes on.

2 The diprotodon may still be remembered in the contemporary stories of the Adnyamathanha and Ngarrindjeri people of Australia. According to Jacinta Koolmatrie, an archaeologist belonging to this Aboriginal heritage, her people speak of a beast they call Yamuti, which could be based upon a memory of the diprotodons that went extinct forty-thousand years ago.

3 Polynesian seafarers and their chickens are known to have reached the coast of South America, in modern-day Chile, by the late first millennium CE. From here, some traveled back to the Polynesian islands bearing the sweet potato, which then diffused as a common crop (kumala) through large regions of the Pacific. Whatever colony those first Austronesian-South Americans settled along this coast was eventually assimilated into other South American groups, notably the Mapuche.

4 Most ethnographic details on the Tikopia are gleaned from We, the Tikopia: A Sociological Study of Kinship in Primitive Polynesia, by Raymond Firth, 1936. Firth’s was the first ethnography ever published on Tikopia society, based on his year-long residence among the islanders during 1928–29, before they had fully accepted Christianity. Most of the details based on archaeology are gleaned from Collapse: How Societies Choose To Succeed or Fail by Jared Diamond.

5 Hurricane Zoe hit Tikopia in 2002. One of the strongest hurricanes ever known up until that time, it eroded the thin bank that separated the freshwater lake from the sea, turning the lake water brackish again and affecting its fish. In 2006, the bank was rebuilt in a project funded by international well-wishers—yachties who’d become fondly acquainted with the islanders during their own Pacific adventures over the decades—a substantial sign of growing interactions between the Tikopia and the West as well as the Tikopia’s increasing acceptance of foreign materials and practices.

6 A canoe documented on Anuta in 2014 was reported to have been built in the late nineteenth century. It was well preserved, seaworthy, and still in use. The Anuta said when they build a canoe, it’s considered a part of the family and they care for it as such.

7 The Tikopia had a saying that brothers never fish together. Alone on a canoe, each brother might be tempted to murder the other in order to inherit the full rights to the family land. A man preferred to fish with his brother-in-law.

8 Couples were free to divorce, though divorce was in practice quite rare. In the event of a divorce, initiated by either party, a woman was welcome to return to her natal home and either partner was free to marry someone else. Children of a divorced couple remained in contact with both parents. A woman who was widowed while her children were still young, however, was expected to remain celibate at least until the children were grown; there was no corresponding expectation for widowed men. There were also rare cases of men marrying two women, typically sisters.

Images

1. Gwion Gwion rock paintings, formerly known as the Bradshaw rock paintings, from the Kimberly region in Australia. Creative Commons.

2. A map showing the dispersal routes of Austronesian peoples. Tracking Austronesian expansion into the Pacific via the paper mulberry plant by Elizabeth A. Matisoo-Smith.

3. An image from the top of a hill on Anuta island. Screenshot from The Forgotten Tribe Of Anuta | 1000 Days For The Planet | Real Wild.2014. Fair use.

4. A canoe built on Anuta island over a century ago, preserved in seaworthy condition, was still in use at least until 2014. Screenshot from The Forgotten Tribe Of Anuta | 1000 Days For The Planet | Real Wild.2014. Fair use.

5. Scene from a village gathering on Tikopia island. Screenshot from Message in a Bottle. 2003. Fair use.

6. Scene from a village on Tikopia island. Screenshot from Message in a Bottle. 2003. Fair use.