by Omar Baig

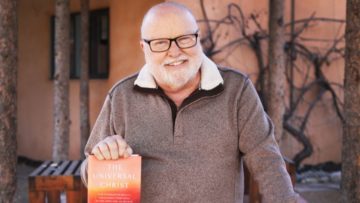

Conservative and Evangelical Christians—with their provincial notions of Jesus as dying on the cross for their sins—denounce the Cosmic Christ of Father Richard Rohr as new age heresy. Yet some Christians may not even realize that Jesus and Christ are not the same. As if, he jokes, Christ was simply the last name of Jesus. By building off the Franciscan mysticism he was ordained in, Fr. Rohr defends the “alternative orthodoxy” of an eternal Christ, through which material reality fully coincides with the spiritual. Bible verses like Colossians 1:17-20 portray Christ as “before all things,” including the Jesus of Nazareth, since “in Him all things hold together.” Ephesians 1:13 affirms our “inherent union” with Christ, for “you too have been stamped with the seal of the Holy Spirit.”

Over three decades of accusations—as an apostate, false prophet, or wolf in sheep’s clothing—have compelled Fr. Rohr to ground his seemingly unorthodox and progressive theological views with extensive biblical scripture and scholarly references. Despite a formal investigation by the Vatican, Rohr remains a priest in good standing with the Catholic Church. Scrutiny only bolsters his belief that one must first know the rules well enough before knowing when they do not apply. Like the cosmos itself, the Jesus of the gospel affirms two parallel drives toward diversity and communion. Rohr’s 1999 essay, “Where The Gospel Leads Us,” for example, extends God’s unconditional love to the whole of creation: since all relationships, including LGBT ones, demand “truth, faithfulness, and striving to enter into covenants of continuing forgiveness of one another.”

Yet most will never move beyond Ken Wilbur’s first stage of spiritual development, which is preoccupied with cleaning up their own self-image as a Good Christian. They judge, put down, and exclude others for their differing practices or views as Bad Christians. Rigid purity codes generate the respectability politics of each church by policing their member’s social behavior and determining their relative standing. This parallels the ego-formation and social conformity of early childhood development, when our sense as an individual separates from our sense of others. But defining yourself by who you aren’t is what led to the extreme polarization of our current politics. Each identity group seems to define themselves more by what they think is wrong with other groups, rather than rally around their shared beliefs or goals.

The False Self

The First Half of Life comprises the cleaning up and growing up stages of spiritual development, which reinforces the False Self: with its calculative mind of “what’s in it for me” and its egocentric fixation with how others view them. The cleaning up stage reduces prayer to something functional: i.e., to achieve a desired effect, like curing their sick Grandma and so on. Formal religious institutions encourage a transactional relationship to get God to like or reward them. Clergy serve as little more than spiritual “middle men,” who facilitate connections between lay members and God, through traditional rules, ritual practices, or receiving of alms. Most merely reassure active members of their moral superiority, elevated spirituality, or future place in Heaven, rather than challenge the False Self’s illusion of control by alienating their most rich, well-fed, or abderian members.

From cleaning up to growing up, the False Self is always on the defensive: i.e., by how it dresses itself up with the personal and social identities it presents to others. The more the False Self fortifies its own boundaries, with what it self-identifies as, the more fragile it becomes to the perceived slights of others. It’s tendency to take offense is inversely proportional to the “spiritual perfection” their ego has deluded themselves into pursuing (i.e., by meeting an arbitrary set of requirements). In the Gospels, Paul referred to this as “the Law,” or the performance principles that measure relative self-worth. These principles underlie the same institutionalized forms of religion that fought Jesus for not following their dogmas and for undermining their synagogues.

The second stage of growing up seeks to understand, speculate, and argue over theories on human communication, social structures, and power differentials. From 20 to at least 50 years of age, the False Self moves away from manipulating how others worship God towards manipulating their own personal conception of God: i.e., as compatible with modern secularism or postmodern metanarratives of spiritual transformation. Most, however, will spend their entire lives in The First Half of Life, either cleaning or growing up. In Fr. Rohr’s experience, many will have to wait until their deathbed before they can finally embrace the inner-peace of their True Self.

The Second Half of Life

Few will make it to the third stage of walking up, which begins the Second Half of Life. Even Liberal “do-gooders” rely, Father Rohr claims, on a pompous and sanctimonious False Self—willing to exploit divisive identity politics if it can help them cobble together enough minorities into a successful voting-bloc. Yet most remain indifferent to actually disrupting the status quo or addressing the most oppressed classes of human labor, farm animals, or critically endangered ecologies. The False Self is happy to stay in the First Half of Life, which upholds the extrinsic “containers” that protect their self-image. Only great love or immense suffering, however, can penetrate the defensive boundaries of The False Self and inspire real spiritual transformation.

Rohr quotes Albert Einstein: “No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.” Thus, if cleaning up means transactional rules and purity codes—while growing up wades more into endless philosophical arguments—then our True Self awakens to the necessity of darkness and the wisdom of not knowing. Despite its embrace of uncertainty, The Second Half of Life is more secure, abundant, and compassionate than The First Half: with its performance principles and group ideologies. It awakens to alternatives to linear models of progression, like spiral dynamics, which upholds the flexibility and spontaneity of natural flows and forms, alongside a conflicting mix of truths and uncertainties.

By surrendering to uncertainty, the True Self is ironically freer than the False Self’s purported autonomy, which is always on the move as it strives for more. In short, the False Self merely says prayers, but the True Self moves towards becoming a prayer. Only the afterimage of The First Half of Life’s private, disconnected, and discreet Self can delude us into thinking that the True Self is ever separate from God. As one dwells further into the expansive uncertainty of themselves, this becoming stillness opens the True Self to greater spiritual truths (i.e., as an already spiritual being, connected to God). Their daily acts of silent meditation inadvertently reveal the greater scope of their local and global impact on others—in the imperial pursuit of their own self-interests—against their previous bias towards meeting some performance principle, like gathering more private wealth.

Showing Up

Father Rohr highlights two groups with a head start in The Second Half of Life—(1) mystics who renounce the performance principles of material and societal success, by retreating to a solitary life of asceticism, and (2) addicts who surrender to a Higher Power, after admitting to being powerless over their addictions. The first echoes Luke’s beatitude, “Blessed are you poor, for the kingdom of God is yours,” whereas the second exemplifies Matthew: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of Heaven.” Fr. Rohr champions the Liberation Theology of poverty as a scandalous state: acknowledging both the Bible’s “preferential option for the poor” and the stark, inequitable concentration of wealth by a relative few. Liberation Theology first spread across Latin America and has since inspired Pope Francis’ recent encyclicals on the life of Saint Francis: who traveled far and wide, promoting a fraternal love that transcends national borders.

Christians will mature into the fourth and final stage of spiritual development by showing up for the most vulnerable segments of the labor class, which carry forth the structural sins of globalization, consumerism, and the status quo. Showing up for others ironically begins with them sitting down and opening up to uncertainty. The Centering Prayer of Father Thomas Keating, for instance, relies on The Cloud of Unknowing—an anonymously published, 14th Century mystical text—as the foundational Christian basis for his twice daily practice of silent mediation. “For when you fix your love on him, forgetting all else,” The Cloud speculates, “the saints and angels rejoice and hasten to assist you in every way.” Even “the souls in purgatory are touched,” and their suffering is lessened, since “your own spirit is purified and strengthened by this contemplative work more than by all others put together.”

“When God’s grace arouses you to enthusiasm,” they continue, “it becomes the lightest sort of work there is and the one most willingly done.” Without grace, it is “very difficult” and “quite beyond you.” In Centering Prayer, it is “usual to feel nothing but a kind of darkness about your mind, or as it were, a cloud of unknowing.” You will “seem to know nothing and to feel nothing except a naked intent toward God in the depths of your being.” “This darkness and this cloud will remain between you and your God,” for your mind cannot “grasp him, and your heart will not relish the delight of his love.” “But if you strive to fix your love on Him, forgetting all else, which is the work of contemplation I urged you to begin,” then God’s goodness “will bring you to a deep experience of himself.”

Antiwork Praxis

Instead of actively changing the world, Centering Prayer disrupts the egocentric agendas of the private, False Self, as the True Self surrenders to the wisdom of unknowing. Silent contemplation, as a spiritual praxis for the Antiwork movement, aims to still the whirlpool of one’s thoughts, which subverts our subconscious obsession over maximizing productivity or chasing after someone else’s standard of success, or judging. Excessive energy use and greenhouse-gas emissions is changing, Fr. Rohr argues, “the planet’s climate in ways that will make it uninhabitable for ourselves and many other species.” Antiwork praxis must address climate change as the central crisis of the twenty-first century, which is “the result of too many human beings using too much energy and taking up too much space on the planet.”

Being open to God, therefore, “means being open to the other creatures upon whom we depend and who depend upon us.” We are not being called to fight an enemy; rather, “the enemy is the very ordinary life we ourselves are leading.” We live each day, Fr. Rohr reminds us, by “the food we eat, the transportation we use, [and] the luxuries [of] long-distance air travel we permit ourselves.” This is both “unjust to those who cannot attain this lifestyle” and “destructive of the very planet that supports us all.” Fr. Rohr references Philippians 2:7, in which Paul explains that God “emptied the divine self, by taking the form of a slave,” and in the cross, God gives of the divine self without limit. As we struggle to deal with climate change, we must always rediscover how the universal Christ is in, with, and for the world.

How does this eternal Christ reveal the insight and power of God’s incarnation, as “the basics of existence” over space and energy, “so we can live in radical interdependence with all other creatures?” In the Christian tradition, Fr. Rohr replies, kenosis or self-emptying is “seen as constitutive of God’s being in creation, the incarnation, and the cross.” The “becoming stillness” of Contemplative Prayer further supports an egoless state of consciousness, by “the attempt to open the self so that God can enter.” And rather than over-inflate their most privileged members’ ritual or institutional displays of piety, the fraternal love of Liberation Theology seeks to address and improve the exploitation of the labor class.

Conclusion

In Capitalist Realism (2009), Mark Fisher examined “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.” Postmodern predecessors like Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek argued that “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism.” Yet to merely encourage the dissemination of anti-capitalist ideas, instead of actively challenging its operant systems, further compounds the very failures it hopes to rectify. The Centering Prayer of Thomas Keating, Cynthia Bourgeault, and Richard Rohr, however, offers a spiritual practice of anti-capitalist resistance that cultivates inner silence, and the mystical wisdom of unknowing, over the mindless consumption of more for less or the equating of one’s work ethic with their self-worth.

“I’m not going to say capitalism is wrong in all aspects,” Fr. Rohr admits, “it does some very real and significant good.” We must “be able to offer an honest critique of a system,” however, “if we want to find a better way forward.” The US, for example, offers residents a free public education before their transition into the workforce. This helps “equalize opportunity and prepare young people to participate productively in the U.S. economy,” which free enterprise would otherwise neglect. A modest, universal basic income, therefore, seems like the logical extension of our public education, which will finally liberate their citizens from the drudgery of traditional employment (i.e., as wage slavery). Companies would have to offer more attractive employment opportunities to compete with opting out of cumbersome commutes or otherwise unfulfilling, bullshit jobs. Contemplative practice could further revolutionize how we “participate productively,” by making us more mindful of the time actively spent between their daily acts of morning and evening silence.