by Ashutosh Jogalekar

“Giving up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879”, by Noel Perrin

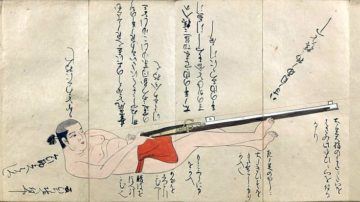

In 1543, a small Chinese pirate sloop with two Portuguese arquebusiers on it sailed into Tanegashima island in Japan. The local feudal lord, Tokitaka, was so impressed when he saw one of the arquebusiers shoot a duck that he promptly ordered two of the guns for a price that was to go down 500-fold over the next seventy years. The same day he ordered his swordsmith to repurpose his skills for manufacturing the new weapon.

That dramatic reduction in price shows the impact the gun had on Japan. In the next hundred years, Japanese gun manufacturing achieved a level of prominence and expertise that in many ways exceeded anything in the West; for instance, the Japanese devised the simple and yet unique expedient of protecting their gunpowder in a water-resistant pouch to prevent a matchlock fizzle, allowing them to take guns into battle comes rain or shine. Japanese metallurgy was also second to none, with cheap and yet effective Japanese copper being the envy of the West. The advantages of the gun became very apparent very quickly; in 1575 at the Battle of Nagashino, for instance, Oda Nobunaga handily defeated Takeda Katsuyori’s cavalry by mowing them down like a scythe with a sophisticated pattern of gunfire. Other engagements followed, including a war with Korea, where the practical utility of the gun was left in no doubt. It looked like, from almost any angle, Japan was set to lead the world in advanced gun warfare for the foreseeable future.

And yet after a hundred years, the reduction of gun warfare was equally dramatic, so much so that the small trickle of Western observers who managed to make it to the island nation after Japan had banned Christians thought that the country existed in a state of primitive ‘Arcadian simplicity’, completely innocent of modern weaponry. Little did they know the history which Dartmouth professor Noel Perrin recounts in this lively volume. Japan remains perhaps the only example of an advanced, intelligent nation that sampled guns and then willingly gave them up for hundreds of years. Perrin explains the why and the how here and speculates on why that might hold some lessons for our own obsession with new weapons and technology. Read more »

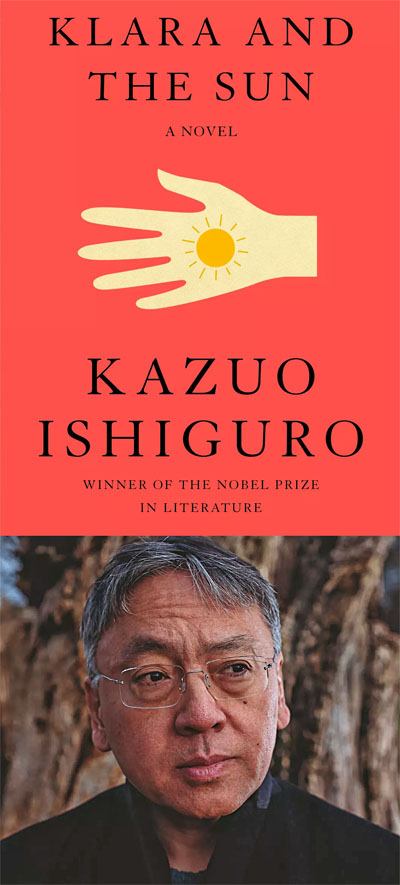

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a