by Brooks Riley

If Wolfgang Porsche, 82, chairman of the supervisory board of Porsche AG, is able to live in a historic landmark villa on the Kapuzinerberg, a forested mountain in Salzburg, he owes a debt to Stefan Zweig, the popular and prolific Austrian writer who bought the rundown 17th century structure in 1917, at a time when it had no electricity, no telephone, little heating and a treacherous path down the mountain to the city.

“I did most of my work in bed, writing with fingers blue with cold, and after each sheet of paper that I filled I had to put my hands back under the covers to warm them.” (The World of Yesterday: Memoirs of a European)

The villa, first conceived as a hunting lodge for Prince-Archbishop Paris von Lodron in the 17th century, was expanded over the following centuries by new owners who gave it new names. Mozart and his sister are said to have performed at the villa. Kaiser Franz Josef bowled there as a boy.

Zweig completely renovated the Paschinger Schlössl, as it is now called, and lived there until 1934, when a fascist police department raided his home on a false pretense. Zweig, who was Jewish, and the best-selling German-language author of that period, read the writing on the wall and moved to London. In 1938, after the Anschluss, his books were burned on Salzburg’s Residenzplatz. Four Stolpersteine serve as reminders of Zweig’s involuntary exit from a city that he loved.

I lived in the cozy shadow of the Kapuzinerberg near the Stefan Zweig villa for four years in the early nineties. At the time, it was still owned by the family who had bought it for a song from Zweig in 1937, but I liked to imagine the cultured author still at home above me—in near solitary splendor—enjoying the best view in town, his only neighbors the novitiates at a nearby Capuchin monastery. Zweig maintained a vast library in his home, and had been a regular at the Café Bazar, which was also my favorite place to soak up the atmosphere over a mélange. Read more »

When promoting her new book in September, Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett stated in an interview as quoted in Politico : “I think the Constitution is alive and well.” She went on – “I don’t know what a constitutional crisis would look like. I think that our country remains committed to the rule of law. I think we have functioning courts.”

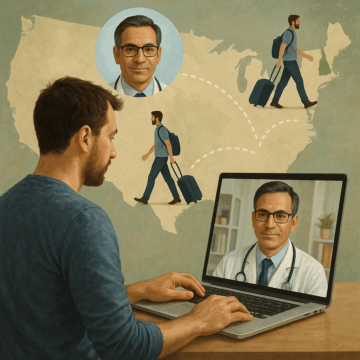

When promoting her new book in September, Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett stated in an interview as quoted in Politico : “I think the Constitution is alive and well.” She went on – “I don’t know what a constitutional crisis would look like. I think that our country remains committed to the rule of law. I think we have functioning courts.” During covid, amid the maelstrom that was American healthcare, a miracle happened. State medical boards suspended their cross-state licensure restrictions.

During covid, amid the maelstrom that was American healthcare, a miracle happened. State medical boards suspended their cross-state licensure restrictions.

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting.

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting. The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random.

The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random. Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024.

Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024. In a previous essay,

In a previous essay,

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

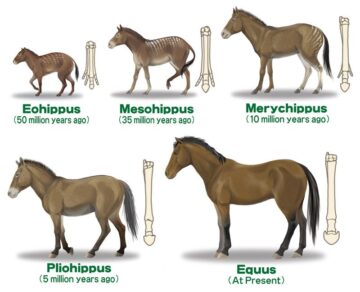

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.