by Rachel Robison-Greene

I can’t know for certain that you are a conscious being with an active mental life. I have access (I think) to my own internal states. I feel my own anxieties, indulge in my own joy, anticipate my own future, and remember my own past. I can’t do the same for you; indeed, for all I know, you might be a philosophical zombie: you might act in every observable way as a conscious human being would act, but, in fact, you might lack internal mental states entirely. Beliefs, desires, hopes, etc., might not happen inside of you. This is The Problem of Other Minds. It is an epistemic problem about what we can really know about human minds other than our own.

In ordinary contexts, though, we don’t think knowledge requires certainty. The idea that you might be a philosophical zombie isn’t a skeptical hypothesis I’m expected to take seriously, especially if I’m enjoying your company or consoling you about a loss. As Bertrand Russell wrote, let a philosopher “get cross with his wife and you will see that he does not regard her as a mere spatio-temporal edifice of which he knows the logical properties but not a glimmer of the intrinsic character. We are therefore justified in inferring that his skepticism is professional rather than sincere.”

In our everyday interactions with one another, we take behavior that is typically caused by certain mental states in our own case to count as sufficient evidence that the same or similar mental states are present in the minds of other people. If you pluck the fruit from the tree, it’s likely because you believe it is ripe. I am justified in drawing that conclusion because that’s likely the belief that would motivate me to pluck the fruit.

This reasoning is good enough for us most of the time in our interactions with other human beings. When it suits us, however, we treat non-human minds with much more skepticism, especially when it is in our interest to do so. Though philosophical behaviorism is no longer in vogue in human psychology, scientists still treat it as gospel when it comes to research on non-human animals. When discussing interactions with animals, a scientific approach involves making observations about stimulus inputs and response outputs without speculating about the inner states of animals whose internal lives we can’t access. We make similar judgments when thinking about the minds of animals that we kill for food. This is The Problem of Animal Minds, and it is much more than an epistemic problem. Read more »

Kazuo Ishiguro often talks about a scene from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre that has influenced his writing. In an interview

Kazuo Ishiguro often talks about a scene from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre that has influenced his writing. In an interview  While teaching English at a Yeshiva in the Bronx, I was surprised one day to become part of a theological thought experiment so creative and meaningful that it has stayed with me ever since. After recently learning that the universe may “die” much sooner than previously thought, I recalled that moment as it offered metaphorical depth and poignancy to a scientific truth.

While teaching English at a Yeshiva in the Bronx, I was surprised one day to become part of a theological thought experiment so creative and meaningful that it has stayed with me ever since. After recently learning that the universe may “die” much sooner than previously thought, I recalled that moment as it offered metaphorical depth and poignancy to a scientific truth. On Yom Kippur this year, I went to church.

On Yom Kippur this year, I went to church. It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so

It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so

In Timur Vermes’ best-selling novel Er ist wieder da (‘He’s back’), Adolf Hitler wakes up in Berlin. Somewhat disoriented after discovering the year is 2011, he soon finds his way to the public eye again: he is understandably regarded as a skilled Hitler impersonator, an excellent ironic act for a 21st-century comedy show. His handlers don’t mind the fact that he never breaks character.

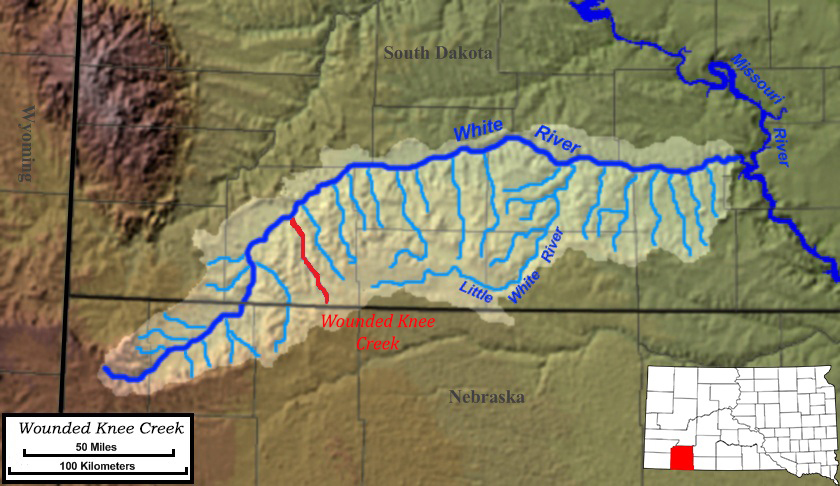

In Timur Vermes’ best-selling novel Er ist wieder da (‘He’s back’), Adolf Hitler wakes up in Berlin. Somewhat disoriented after discovering the year is 2011, he soon finds his way to the public eye again: he is understandably regarded as a skilled Hitler impersonator, an excellent ironic act for a 21st-century comedy show. His handlers don’t mind the fact that he never breaks character. The Lakota name for Wounded Knee Creek is Čaŋkpe Opi Wakpala. The first letter is a -ch sound. The ŋ signifies not an n, but nasalization as when you say unh-unh to mean no.

The Lakota name for Wounded Knee Creek is Čaŋkpe Opi Wakpala. The first letter is a -ch sound. The ŋ signifies not an n, but nasalization as when you say unh-unh to mean no.

1. Roses

1. Roses

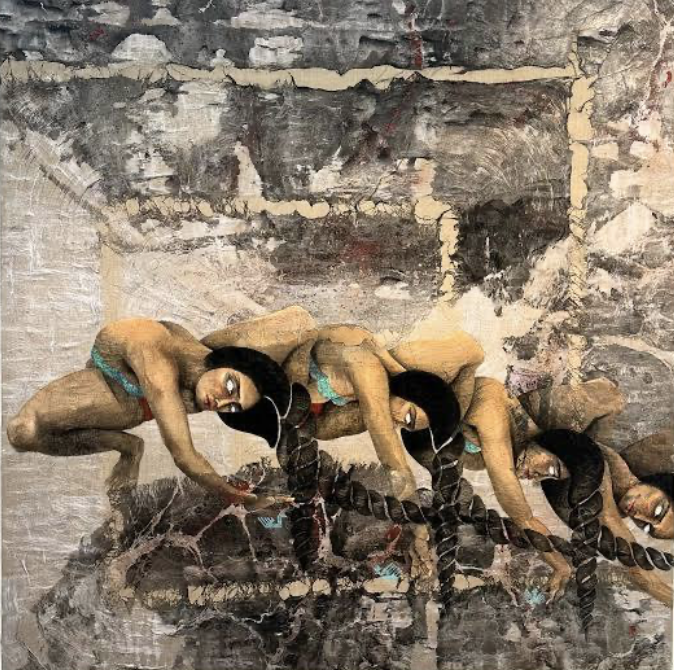

Hayv Kahraman. Rain Birds Ritual, 2025.

Hayv Kahraman. Rain Birds Ritual, 2025. Morgan Meis and I have been talking about art for years. We’re friends and interlocutors, so I’ll refer to him by first name here for the sake of transparency. Morgan writes about painting; I write about movies. We spent the pandemic exchanging letters with each other about films by Terrence Malick, Lars von Trier, and Krzysztof Kieślowski. These letters were later collected in a mad book called

Morgan Meis and I have been talking about art for years. We’re friends and interlocutors, so I’ll refer to him by first name here for the sake of transparency. Morgan writes about painting; I write about movies. We spent the pandemic exchanging letters with each other about films by Terrence Malick, Lars von Trier, and Krzysztof Kieślowski. These letters were later collected in a mad book called