by TJ Price

Saying “I don’t know” is one of the great joys of my adult life. I revel in the phrase. I freely and openly admit honest ignorance, in the service of learning more, hungrily, with an avid—and, perhaps, slightly obsessive—need. It was not always this way.

For most of my early life, in fact, I was uncomfortable saying it. It was as if I would be admitting to a lack of some critical function, for which I could be judged and dismissed—or, worse, taught—accordingly. Confronted with the new or unfamiliar, I might fake familiarity, bluffing my way through or fleeing from proof of my ignorance, but the dread of challenge to my knowledge dogged my every step. This was perhaps the first flickers of so-called “imposter syndrome”—I was terrified that every moment could prove the moment when everyone discovered I was a fraud, all along. That I wasn’t as smart as they thought I was, which would then prove to me that I wasn’t as smart as I thought I was.

Idyll:

Despite this fear of inadequacy, I have secretly always wanted to be a professional student. I had dreams of vaulted ceilings and cloistered libraries. Of chalkboards and dust and long hours turning pages. The actual schools I did attend held no real value to me—I had ideals of education, from the very beginning, which eluded me and continue to elude, I think, most in this country. These ideals may have been touched by a young romanticism, but the core of them remains the same—

Credo:

I believe education should not be a gauntlet, should not be cheerless. It should be gentle, inquisitive. It should be sets of questions to which answers are hard-won, but not in the way of contest or grade. I still, to this day, believe fully that one of the great evils in the world is that there is something that every single person is curious about, and that—often enough, for one reason or another—they just don’t get to follow that thread. Instead of being encouraging, there is a rigor involved, a stern hand-slap, a sharp return to inculcation by rote.

Hypothesis:

Education is less an instilling of foreign elements, treating knowledge as immigrant to our brain, but more a revealing—a guided perambulation via neuronal paths—lighting associations one by one as we go. Read more »

Philip Graham: The home page of your new and expanded author’s website,

Philip Graham: The home page of your new and expanded author’s website,

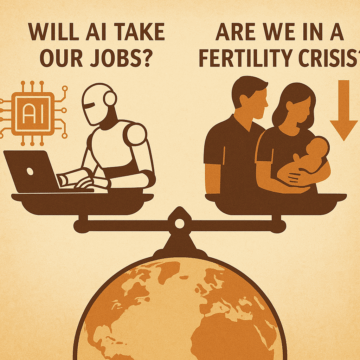

The question of the day on everyone’s minds is whether AI is a boom or a bust. But if we lift our eyes ever so slightly from the question of the day and look at the bigger picture, two bigger questions come into view.

The question of the day on everyone’s minds is whether AI is a boom or a bust. But if we lift our eyes ever so slightly from the question of the day and look at the bigger picture, two bigger questions come into view. In Arabic, the word

In Arabic, the word  Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Temple, Jogjakarta, Indonesia, October 2025.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Temple, Jogjakarta, Indonesia, October 2025.