by Brooks Riley

If Wolfgang Porsche, 82, chairman of the supervisory board of Porsche AG, is able to live in a historic landmark villa on the Kapuzinerberg, a forested mountain in Salzburg, he owes a debt to Stefan Zweig, the popular and prolific Austrian writer who bought the rundown 17th century structure in 1917, at a time when it had no electricity, no telephone, little heating and a treacherous path down the mountain to the city.

“I did most of my work in bed, writing with fingers blue with cold, and after each sheet of paper that I filled I had to put my hands back under the covers to warm them.” (The World of Yesterday: Memoirs of a European)

The villa, first conceived as a hunting lodge for Prince-Archbishop Paris von Lodron in the 17th century, was expanded over the following centuries by new owners who gave it new names. Mozart and his sister are said to have performed at the villa. Kaiser Franz Josef bowled there as a boy.

Zweig completely renovated the Paschinger Schlössl, as it is now called, and lived there until 1934, when a fascist police department raided his home on a false pretense. Zweig, who was Jewish, and the best-selling German-language author of that period, read the writing on the wall and moved to London. In 1938, after the Anschluss, his books were burned on Salzburg’s Residenzplatz. Four Stolpersteine serve as reminders of Zweig’s involuntary exit from a city that he loved.

I lived in the cozy shadow of the Kapuzinerberg near the Stefan Zweig villa for four years in the early nineties. At the time, it was still owned by the family who had bought it for a song from Zweig in 1937, but I liked to imagine the cultured author still at home above me—in near solitary splendor—enjoying the best view in town, his only neighbors the novitiates at a nearby Capuchin monastery. Zweig maintained a vast library in his home, and had been a regular at the Café Bazar, which was also my favorite place to soak up the atmosphere over a mélange.

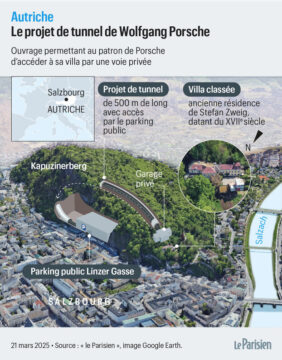

Now Porsche, who bought the estate in 2020 and is the son of Ferry Porsche—car designer and member of the SS during the Third Reich—has paid the city the modest sum of €48,000 for a right-of-way that will enable him to construct a 500-meter long private tunnel to the villa and a new underground 9-car private garage, so that he can have easier access to the city. (The current access road is narrow and winding, and often filled with tourists visiting a Mozart Memorial on foot.)

In spite of loud protests against it, the city approved the tunnel in September. The only remaining obstacle is the state of Salzburg, which has yet to approve the project.

Salzburg owes a lot to its master builders of yore—theocratic rulers with mandates from Rome or direct from God: the bon-vivant Prince-Archbishop Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau, who built himself the Mirabell Palace and a colorful mausoleum, as well as the magnificent Salzburg Cathedral, a light-filled baroque antidote to the gloom of gothic architecture.

Or Prince-Archbishop Paris von Lodron, who took advantage of Salzburg’s neutrality in the Thirty Years’ War to fortify the city and add to the density of landmark buildings that still defines Salzburg’s inimitable cityscape.

Today’s would-be master builders are rich old geezers with ‘needs’.

There’s Donald Trump, 79, and his ballroom, a 90,000-square-foot (8,360 square meters) inflated new wing of the White House that already looks like a gilded warehouse for rental furniture. Designed to seat 900 people for state dinners, this vanity project will dwarf the main building, forever reminding us of an old man’s folly—unless it is stopped from being built or is later torn down.

But Trump isn’t the only ‘master builder’ with inappropriate ambitions: Porsche, unlike Trump, isn’t tearing something down, but his €10-million tunnel could possibly damage the small Hausberg (home mountain) that up to now has been mercifully spared because of its landmark status as a nature reserve.

Tunneling at an incline up to 5o meters along a distance of 500 meters is not a routine endeavor. According to AI, “a tunnel going uphill is generally more complicated due to issues with groundwater management and ventilation.” Then there’s the issue of “varying geological conditions, such as soft soils, hard rock, or faults, which require specific support methods.”

I personally worry if all precautions will be taken to prevent a landslide onto the busy Linzer Gasse directly beneath the Kapuzinerberg. (In a time of climate change, when rain-drenched mountains can fall apart on their own—even without the stress of a tunnel—this prospect must surely loom as a possibility.)

I personally worry if all precautions will be taken to prevent a landslide onto the busy Linzer Gasse directly beneath the Kapuzinerberg. (In a time of climate change, when rain-drenched mountains can fall apart on their own—even without the stress of a tunnel—this prospect must surely loom as a possibility.)

I feel for my old neighbors having to endure possibly years of construction-site disruptions, just so the Porsches can get to the Salzburg Festival on time.

One might wonder if the current mayor of Salzburg, a Social Democrat who worked for Porsche for more than 25 years, is representing the people of Salzburg or his old employer. But it was actually his predecessor, a conservative ÖVP mayor, who gave Porsche the right-of-way without consulting the city council. When the secret deal came to light earlier this year, it caused a storm of protest from the public, and from the Green party and the Communists (2nd strongest party in Salzburg). The scandal is ongoing.

Porsche has every right to build himself a grand underground garage. His villa and own land enjoy Kellerrecht, the right to build under one’s own property—all the way to the earth’s core, if one so wishes.

Tunneling under land that belongs to Salzburg is another matter altogether, and coupled with the secret nature of the original deal, without any official independent assessment of the project (Porsche provided his own assessment), an atmosphere of mistrust and resentment has arisen against special privileges accorded to the wealthy.

“The SPÖ’s now approval of the project is a political capitulation. Together with the ÖVP and FPÖ, they are not only dismissing sound legal expertise – they are setting a precedent which sends the message: Anyone with enough money can do this. This tunnel is not simply a private access. It is a monument to the privileges of the super-rich.” (Stefanie Ruep, Der Standard, September 3, 2025)

History can be cruel: When Zweig lived in his ‘Villa Europa’, it was a magnet for the European intellectual stars of the age, Thomas Mann, Hugo von Hoffmansthal, Franz Werfel, Richard Strauss, Arthur Schitzler, James Joyce, to name a few. They all managed to get to the villa via the existing narrow winding road. If the tunnel is built, it will offer nothing more than an extravagant way for Herr Porsche to get to town.

It had been hoped that the Zweig Villa might become a museum, but no one stepped up to buy it for such a purpose. When Porsche bought it and decided to live there himself, it must have been a sad moment, especially for the impressive Stefan Zweig research center attached to the University of Salzburg, which safeguards his legacy.

In an odd coincidence, Zweig also concerned himself with ‘master builders’. But his were writers and thinkers—master builders of the spirit, not the conspicuous consumers of luxury and preferential treatment.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.