by Tim Sommers

The economy is not a force of nature. We have some control over it. Granted, it’s also not like a machine controlled directly by levers, switches, and buttons either. But when the state acts, intentionally or not, it often influences the distribution of income and wealth. More often than not, it influences the distribution of wealth and income in reasonably predictable ways. It seems to me that, for this reason alone, we should care what the ideal distribution of wealth should be. The ideal distribution is, at a minimum, one factor we have an ethical obligation to take into account in governing.

Some people say that any ideal distribution is unrealistic, impossible to achieve. That’s alright though. Ideals – perfectionism, utilitarianism, the Ten Commandments – are, as they say, honored as much in their breach. We should still have ideals to follow.

Others say that trying to enforce any particular distribution – equality, first and foremost – leads to coercion and political oppression. I think they say this mostly because they have frightening real-world cases in mind. But people also do terrible things in pursuit of freedom, justice, or whatever.

You certainly can pursue equality in a repressive way. Say, seize everyone’s property, redistribute it, and redo that every so often to maintain equality. But you could also, as I implied above, mostly regard equality (or whatever the correct principle is) as a kind of tie-breaker. For example, the point of health care is not the distribution or redistribution of wealth per se, but when you must decide between two approaches one of which takes you closer, the other further away, from the ideal distribution, there’s nothing repressive about going with the one that also has a positive effect on the distribution of wealth and income. In other words, there is nothing inherently oppressive about pursuing more distributive equality. It just depends on how you do it.

Some people (libertarians, for example) believe that people deserve whatever they can obtain from fair or just initial aquations and/or just transfers – where neither the acquisitions nor the transfers involve force, fraud, or theft. Where these are unjust, the state should act to rectify the situation, but at no point does it rely on the distribution of wealth to decide anything. One problem with this view is that the current distribution of wealth is largely the result of force, fraud, or theft. Robert Nozick, plausibly the most influential libertarian of them all, surprisingly suggests that solution (at least sometimes) is to follow John Rawls’ preferred distributive principle – the least well-off should be as well-off as possible.

A more serious problem for libertarians is that it is not clear that one can even define just acquisition or transfers without resorting to distributive claims at some point. John Locke and Nozick both say just acquisitions involve “mixing your labor” with something, but then say it is limited in that you must “leave enough and as good for others.” Isn’t that a distributive principle? Or consider property rights. Not the version of property rights that philosophers often focus on, because it doesn’t seem crazy, at least about these sorts of property rights, to say they are “natural” rights. Consider zoning law instead. It involves property rights, but zoning law doesn’t seem like it can be derived from natural laws. Zoning and rezoning creates or addresses various problems, creates or forecloses various opportunities, and it also impacts the distribution of wealth. It seems arbitrary to me to say that you should never take the distributive impact of zoning into account.

So, far I have argued that even if distributive justice it is an ideal that we will never fully achieve, it’s still worth trying to figure out what it is. I argued that there is nothing inherently repressive about attempting to achieve a just distribution. And that focusing only on rights to obtain or transfer property to avoid distributive questions is probably not workable. We are likely to fall back onto questions about the fairness of various possible distributions. So, what is the ideal distribution of wealth and income?

In a Kindergarten everybody gets an equal share. Our first thought is probably to distribute the coconut on the desert island on which we are stranded equally. Equality is the default distributive principle in many contexts.

Funny thing about equality, you can always make things more equal, reduce the amount of inequality, by just taking stuff away from the well-off – even if you don’t give it to anybody. You can always get closer to equality by taking stuff away – which makes some people worse off – even if you don’t give it to someone else (who would then be better off). In other words, equality tells us to sometimes prefer situations were some are worse off and none or better off relative to the status quo. This is called the leveling-down problem. Many philosophers take it to indicate that equality, in an of itself, is not what people care about. What do they care about? Maybe, poverty, immiseration, the plight of the worst-off?

Rawls argued for the “difference principle,” which says that inequalities are only justified if they also work to the advantage of the least well-off. This is called prioritarianism since it gives distributive priority to the worst off. Rawls argues for absolute priority. But this seems to create a nested leveling-down problem. For example, if there were a policy that would increase middle-class wages, but from which no benefit at all would go to the least well-off, it violates the difference principle.

Here’s a different way to deal with the least well-off. Why not say that everyone is entitled to a sufficient amount of income and wealth to avoid poverty and have enough to lead a decent life? Call this sufficientarianism. One issue is how to set the sufficiency level. What is the minimum? Also, it’s exclusive focus on the less well-off means it ignores another possible concern about inequality.

Limitarianism argue that no one should have more than a certain amount. “No billionaires,” for example. They argue that democracy and liberty are impossible in a society with too much inequality. One problem limitarians share with sufficientarians, however, is how to set a threshold. How much is too much?

If we combine these two views, we get a promising distributive approach that we might call sufficiency limitarianism. No one should have too little or too much. But this doesn’t solve the issue of how to set a threshold.

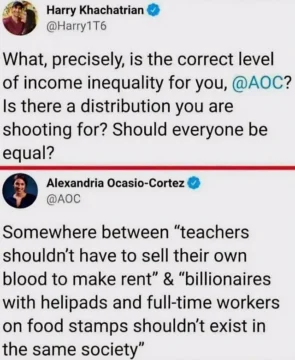

Consider this. What if people don’t care about things being as equal as possible, but only about avoiding things being too unequal. The distribution within a certain range would be a matter of indifference, but falling below or exceeding the range would be considered problematic.

This is the view that I have come to. I call it range egalitarianism. Empirical research suggests that most Americans believe that there is too much inequality, but that some level of inequality is morally fine. Most Americans are range egalitarians, then. It is a response, again, to the idea that you don’t have to love equality as such, to fear inequality that leaves some unable to meet their basic needs and others with the power to bend the rest of us to their will.

_________________________________

Appendix: Nozick on Rawls

“Assuming (I) that victims of injustice generally do worse than they otherwise would and (2) that those from the least well-off group in the society have the highest probabilities of being the (descendants of) victims of the most serious injustice who are owed compensation by those who benefited from the injustices (assumed to be those better off, though sometimes the perpetrators will be others in the worst-off group), then a rough rule of thumb for rectifying injustices might seem to be the following: organize society so as to maximize the position of whatever group ends up least well-off in the society.”