by Christopher Hall

What does it mean to turn somebody into an object, either literally, by killing them, or in a more conceptual sense, by robbing them of freedom of thought and action? This, according to Simone Weil in her celebrated essay on the Iliad, is the central topic of that poem:

Here we see force in its grossest and most summary form – the force that kills. How much more varied in its processes, how much more surprising in its effects is the other force, the force that does not kill, i.e., that does not kill just yet. It will surely kill, it will possibly kill, or perhaps it merely hangs, poised and ready, over the head of the creature it can kill, at any moment, which is to say at every moment. In whatever aspect, its effect is the same: it turns a man into a stone. From its first property (the ability to turn a human being into a thing by the simple method of killing him) flows another, quite prodigious too in its own way, the ability to turn a human being into a thing while he is still alive. He is alive; he has a soul; and yet – he is a thing. An extraordinary entity this – a thing that has a soul. (Mary McCarthy’s translation)

A thing that has a soul. Is this not a rather routine definition of what a human being already is? In one line of thinking, a human being is an object, and no amount of force is needed to make this so. We are the same kind of stuff as rocks, clouds and black holes, even if one feels Weil would very much balk at this description, and insist that the human being, properly understood, is no sort of object at all. Why insist that force makes us into this “extraordinary entity” otherwise? Force may exercise the majority of its workings on the human object, but its ultimate goal and function, in Weil’s view, is an attack on the subject. Unless we are of the opinion that such a subject doesn’t actually exist – and there are plenty around who are – then force does indeed enact something terrible on the human being, whether we subsist, at least in part, as objects or not.

But what does that entail, exactly – the transition from subject to object? Read more »

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.

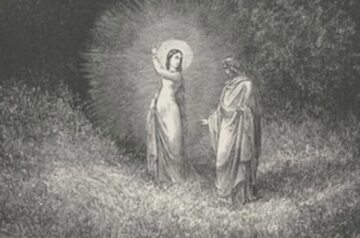

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing.

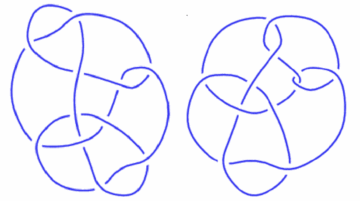

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing. Benny Andrews. Circle Study #2, 1972.

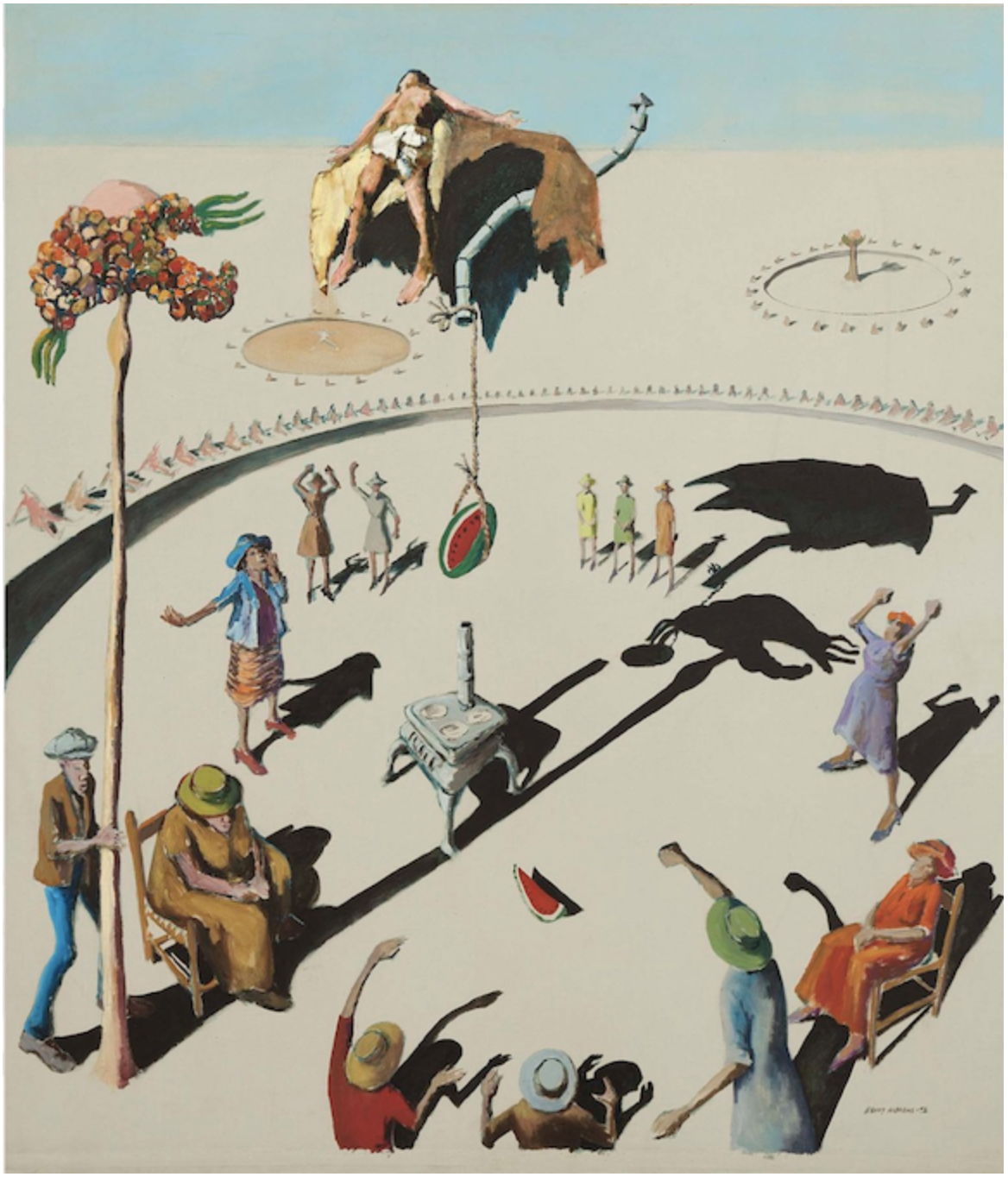

Benny Andrews. Circle Study #2, 1972.

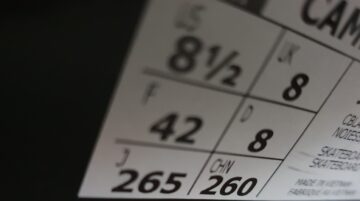

Mathematics is

Mathematics is