by Akim Reinhardt

We’re circling the Sun at a rate of between 18.20–18.83 miles per second. It is not a fixed speed because Earth travels on an ellipsis, and moves a hair faster when it’s closer to the Sun than it does when further away. It averages out to about 67,000 miles per hour over the course of the year. At that speed, a full revolution is 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 46 seconds in the making. At least for now.

Each year, Earth’s voyage around the Sun takes just a little bit longer, to the tune of roughly 3 nanometers per second. It’s minuscule, but adds up over time. Since the solar system’s inception 4.571 billion years ago, Earth is moving 22 mph slower.

The main reason is that Earth is drifting ever so slightly away from the Sun, stretching out the orbital path, and lengthening the duration of a revolution.

We’re not fleeing the Sun so much as it’s pushing us away. As the Sun’s hydrogen core transmogrifies into helium through the process of nuclear fusion, the Sun loses somewhere in the neighborhood of 4 million tons of mass every second. Since that process began billions of years ago, the Sun has lost mass equivalent to 1 Saturn, or approximately 95 Earths if you prefer to think about it in homier terms. The Sun also suffers particle loss through Solar Wind, and that has resulted in its shrinking by another 30 Earths or so. Solar flares and coronal mass ejections also steal away mass. In all, the Sun is ~1027 kg lighter than it was at the birth of our Solar System. Here’s what 1027 looks like written out in digits:

1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

Since a ton equals two-thousand, feel free to add another three zeroes and flip that one to a two. Then again, a gram ain’t much, so maybe just leave it as is, stare at it a bit, and try to feel the full weight of it. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.

Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me.

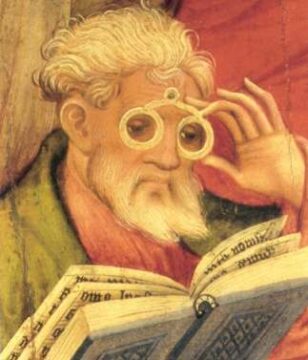

Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me. I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

It might strike you as odd, if not thoroughly antiquarian, to reach back to Aristotle to understand gastronomic pleasure. Haven’t we made progress on the nature of pleasure over the past 2500 years? Well, yes and no. The philosophical debate about the nature of pleasure, with its characteristic ambiguities and uncertainties, persists often along lines developed by the ancients. But we now have robust neurophysiological data about pleasure, which thus far has increased the number of hypotheses without settling the question of what exactly pleasure is.

It might strike you as odd, if not thoroughly antiquarian, to reach back to Aristotle to understand gastronomic pleasure. Haven’t we made progress on the nature of pleasure over the past 2500 years? Well, yes and no. The philosophical debate about the nature of pleasure, with its characteristic ambiguities and uncertainties, persists often along lines developed by the ancients. But we now have robust neurophysiological data about pleasure, which thus far has increased the number of hypotheses without settling the question of what exactly pleasure is. Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Praise of Shadows. Shalimar Bagh, Lahore, December 10, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Praise of Shadows. Shalimar Bagh, Lahore, December 10, 2023.

Andrew Torba, Christian Nationalist founder of the rightwing social media site Gab, recently argued on his podcast that the fact that many of the most beloved Christmas songs were written by Jewish composers was part of a conspiracy to take Christ out of Christmas: to secularize one of the holiest Christian holidays and allow Jews to subtly infiltrate Christian-American culture with their own agenda. He might just be right.

Andrew Torba, Christian Nationalist founder of the rightwing social media site Gab, recently argued on his podcast that the fact that many of the most beloved Christmas songs were written by Jewish composers was part of a conspiracy to take Christ out of Christmas: to secularize one of the holiest Christian holidays and allow Jews to subtly infiltrate Christian-American culture with their own agenda. He might just be right.