by Ada Bronowski

The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.

The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.

Therein, of course, lies the rub. It is contained in two words: constancy and effort. And with them, the beginning and ending of morality.

Aristotle himself is rather pessimistic about his beautifully elaborated enterprise. He ends his Ethics – as explosive and powerful then as it is now (my goggle-eyed students confirm as much) – with a note to the effect that failing, as we almost all do, to become the ideal moral agent, through lack of time, will or stamina, we should rest content with obeying the laws of the land. They have been written by wiser people than us and especially are the fruit of a collaboration over generations of joint – if curtailed – effort towards the good. If constancy cannot be maintained over one’s own individual lifetime, a constancy over generations in the concern for constancy and the realisation of personal failure to live up to it, is an honourable compromise. If moral behaviour is a mirage some of us like to pursue more than others, a collective acknowledgement that we try and fail is the best we can do, building legal systems across political eras that make up for personal inconstance, laziness and lack of energy to improve. Read more »

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons.

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons. I teach at a large, public university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. For about a decade now, the upper administration has had a habit of sending “comforting” emails whenever there’s a major school shooting. Of course there are far too many school shootings in America to send a note for each one, so I suppose the administration tries to keep it “relevant,” for lack of a better word. These heartfelt missives arrive in my Inbox once or twice a year, typically after some lunatic shoots up a college campus. So far as I can tell, they go to everyone. To every faculty member, staff member, and student on campus. To 25,000 people or more.

I teach at a large, public university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. For about a decade now, the upper administration has had a habit of sending “comforting” emails whenever there’s a major school shooting. Of course there are far too many school shootings in America to send a note for each one, so I suppose the administration tries to keep it “relevant,” for lack of a better word. These heartfelt missives arrive in my Inbox once or twice a year, typically after some lunatic shoots up a college campus. So far as I can tell, they go to everyone. To every faculty member, staff member, and student on campus. To 25,000 people or more.

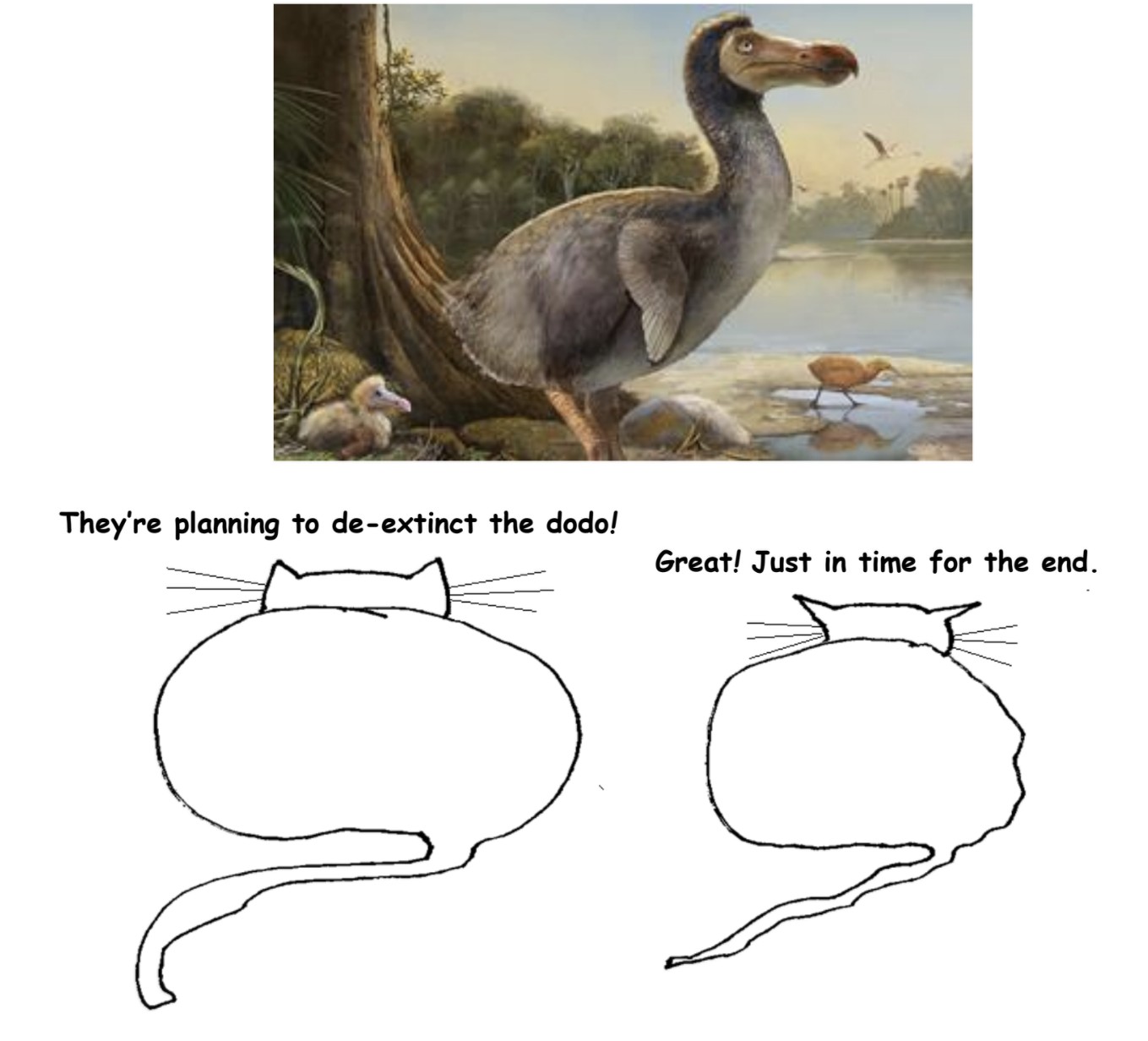

Will re-branding Covid help people start acting to protect themselves from it? Maybe we need an ad campaign to kick-start public health. Outside of judicial rulings and before marketing, we had religious leaders to remind us to the best ways to survive, and before that we had stories passed down for generations to help keep children safe from harm by altering their behaviour,

Will re-branding Covid help people start acting to protect themselves from it? Maybe we need an ad campaign to kick-start public health. Outside of judicial rulings and before marketing, we had religious leaders to remind us to the best ways to survive, and before that we had stories passed down for generations to help keep children safe from harm by altering their behaviour,