by Jonathan Kujawa

The State of Georgia has a lottery guaranteed to turn an enterprising 3QD reader into a millionaire [1].

Playing the lottery can be fun. It is a tradition for Anne and me to buy lottery tickets when stopping for gas on long road trips. Imagining what you’d do with our new wealth is a fine way to pass the long hours it takes to cross the panhandle of Texas. Occasionally, we win back the cost of the ticket. Once or twice, we even doubled our money.

The lottery is often said to be a tax on the mathematically challenged. That saying is certainly nonsense. Pretty much nobody thinks the odds are in their favor. People who buy lottery tickets do so in hope, desperation, or with a “hey, somebody has to win; why not me?” attitude.

After all, the odds of winning the grand prize in the Powerball is 1 in 292,201,338. Every adult in the European Union could buy a ticket, and they might still miss the winning ticket. I could spend $1,000,000 on each of the twice-weekly Powerball drawings, and it would take me more than five years to get through all the possible combinations.

There are a few things with worse odds. A decade ago here at 3QD we talked about how a well-shuffled deck of playing cards is virtually certain to be in an order never before seen in the history of the universe. I wouldn’t bet on guessing that order. But among everyday things, the odds of winning a big lottery are about as bad as it gets.

Gambling odds favor the house. After all, they wouldn’t offer the game if they didn’t expect to make money over the long run. The odds are ever in their favor. Read more »

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III.

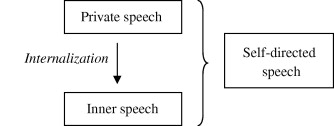

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III. As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

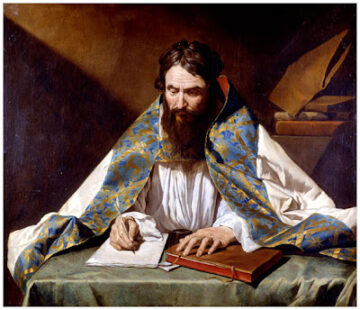

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

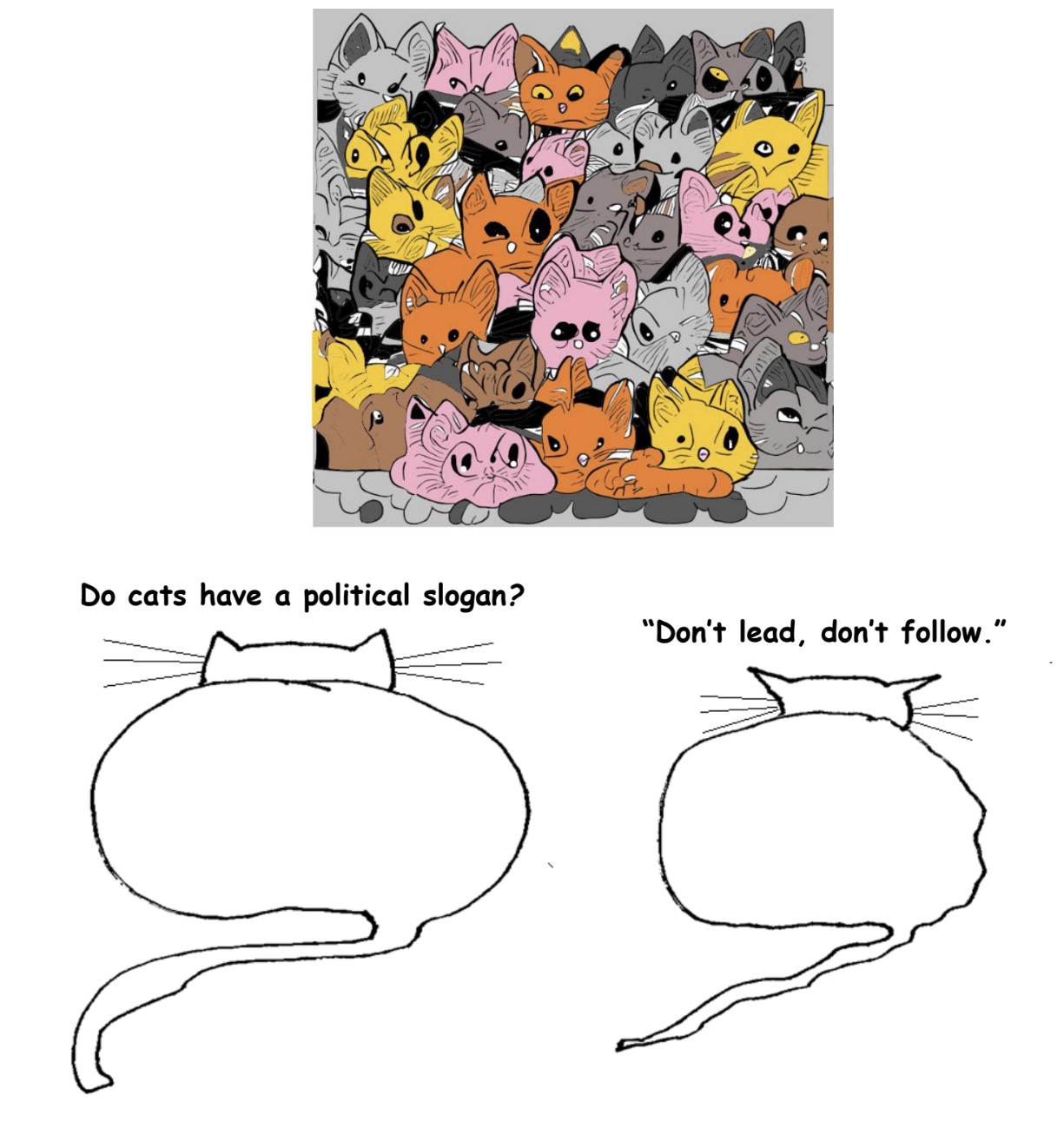

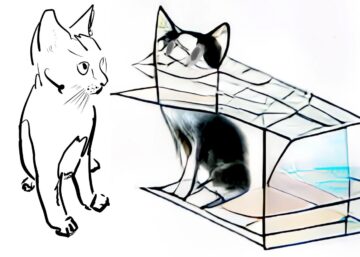

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made.

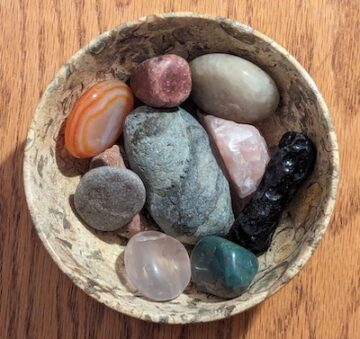

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made. I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones.

I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones. Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.

Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.