by Raji Jayaraman

Vijay was the smartest kid in class. It was a small class, and we weren’t especially bright, but I don’t mean that he was smart in a big-fish-small-pond sense. I mean it in absolute terms. He was a math genius. Short and slight of build there was nothing remarkable about his appearance, at least not neck-down. Neck-up, it was a different story. He had a massive head and we’re talking Boss Baby proportions. On anyone else, that head would have been fair game for mockery. But perched on Vijay’s shoulders, with a brain that size, it seemed like the only feasible design choice.

The boarding school we attended wasn’t especially prestigious. It wasn’t Mayo or Doon, where blue-blooded Indians waitlisted unborn children who, by accident of birth, were predestined to rule. No, the currency for admission wasn’t pedigree. It was money. There were three groups of students who could afford to attend our school. The first was rich kids, whose parents paid out of pocket. Some belonged to the petty nobility who, despite the half-century old abolition of titles, had managed to retain some ancestral wealth. Theirs was old money. It was solid, with no need for external trappings. Indeed, their lack of pretension was so flagrant it bordered on deceit. In middle school, for instance, we had to cancel our third and final run of “You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown” because one of the lead actors’ fathers, L.’s dad, died. As the eldest son, L. had to go home to perform his father’s final rites. Snoopy never returned to school because he was now the Raja of P.

The new money was different. They had generous monthly allowances and wore designer clothes with fancy French names I couldn’t pronounce: Es-spirit, Die-ore, Gukki. Many of these kids belonged to families who, by hook or crook, had secured state monopolies in key industries of India’s post-independence “licence-Raj”. Others were expatriates whose parents worked in Indian joint ventures, or belonged to well heeled families from neighbouring countries. Read more »

January 1, 2024. Happy New Year! Just eleven months and five shopping days before Election 2024. Whether you find it comforting that 2024 also happens to contain an extra day might be the best marker of how Political Seasonal Affective Disorder has impacted you. Personally, I haven’t been sleeping particularly well.

January 1, 2024. Happy New Year! Just eleven months and five shopping days before Election 2024. Whether you find it comforting that 2024 also happens to contain an extra day might be the best marker of how Political Seasonal Affective Disorder has impacted you. Personally, I haven’t been sleeping particularly well. The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when

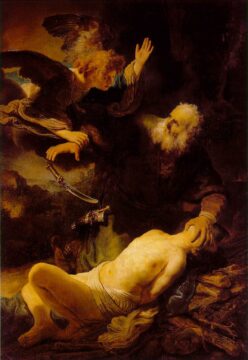

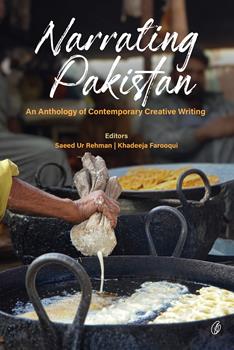

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.

Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me.

Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me. I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

It might strike you as odd, if not thoroughly antiquarian, to reach back to Aristotle to understand gastronomic pleasure. Haven’t we made progress on the nature of pleasure over the past 2500 years? Well, yes and no. The philosophical debate about the nature of pleasure, with its characteristic ambiguities and uncertainties, persists often along lines developed by the ancients. But we now have robust neurophysiological data about pleasure, which thus far has increased the number of hypotheses without settling the question of what exactly pleasure is.

It might strike you as odd, if not thoroughly antiquarian, to reach back to Aristotle to understand gastronomic pleasure. Haven’t we made progress on the nature of pleasure over the past 2500 years? Well, yes and no. The philosophical debate about the nature of pleasure, with its characteristic ambiguities and uncertainties, persists often along lines developed by the ancients. But we now have robust neurophysiological data about pleasure, which thus far has increased the number of hypotheses without settling the question of what exactly pleasure is. Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Praise of Shadows. Shalimar Bagh, Lahore, December 10, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Praise of Shadows. Shalimar Bagh, Lahore, December 10, 2023.