by Raji Jayaraman

Vijay was the smartest kid in class. It was a small class, and we weren’t especially bright, but I don’t mean that he was smart in a big-fish-small-pond sense. I mean it in absolute terms. He was a math genius. Short and slight of build there was nothing remarkable about his appearance, at least not neck-down. Neck-up, it was a different story. He had a massive head and we’re talking Boss Baby proportions. On anyone else, that head would have been fair game for mockery. But perched on Vijay’s shoulders, with a brain that size, it seemed like the only feasible design choice.

The boarding school we attended wasn’t especially prestigious. It wasn’t Mayo or Doon, where blue-blooded Indians waitlisted unborn children who, by accident of birth, were predestined to rule. No, the currency for admission wasn’t pedigree. It was money. There were three groups of students who could afford to attend our school. The first was rich kids, whose parents paid out of pocket. Some belonged to the petty nobility who, despite the half-century old abolition of titles, had managed to retain some ancestral wealth. Theirs was old money. It was solid, with no need for external trappings. Indeed, their lack of pretension was so flagrant it bordered on deceit. In middle school, for instance, we had to cancel our third and final run of “You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown” because one of the lead actors’ fathers, L.’s dad, died. As the eldest son, L. had to go home to perform his father’s final rites. Snoopy never returned to school because he was now the Raja of P.

The new money was different. They had generous monthly allowances and wore designer clothes with fancy French names I couldn’t pronounce: Es-spirit, Die-ore, Gukki. Many of these kids belonged to families who, by hook or crook, had secured state monopolies in key industries of India’s post-independence “licence-Raj”. Others were expatriates whose parents worked in Indian joint ventures, or belonged to well heeled families from neighbouring countries.

The second group of students had their fees defrayed in one of two ways. Either they were connected to American missionaries whose harvest of souls was recompensed through church scholarships. Or they were day scholars whose parents taught at the school. Most of these kids were white, which added to the school’s international caché. Between them, these two groups had the major vices more or less covered. The rich kids smoked dope and snorted coke. The missionary kids got drunk and lost their virginities on the empty pews between church services.

Then there was us: children whose fees were covered by their parents’ employers. Some were foreign diplomats or corporate executives stationed in India or, more often, U.N. employees from the subcontinent who were stationed abroad. My parents fell into this last category and, as far as I know, so too did Vijay’s. They were well-educated but had neither money nor social status. And it showed. Most of us, including Vijay, were nerds. Vijay’s nerdiness came from his natural intelligence. The rest of us studied because, in the absence of money or social networks, education was all we had going for us. I remember an American exchange student saying to me once, “You dress like your dad is on welfare.” Because I didn’t know what it meant to be “on welfare”, I asked another American to explain. The first kid wasn’t wrong. Our clothes were always two sizes too big because they were purchased in six-month intervals during school holidays, the idea being that we would grow into them over the course of the school term. For some reason, that never seemed to happen.

We stumbled through our teenage years in unlaced high tops and heavy, too-long, too-baggy jeans. Like hip hop stars in the nineties, except that it was the eighties and no one is ever contemporaneously ahead of their time. We didn’t look cool, just pathetic. For someone so unfashionable, it came as a surprise when Vijay showed up to school one term with a brand-new sports watch, which was waterproof and pressure resistant up to thirty metres. The fact that he made such a big deal of this particular feature was the source of great mirth among the guys. Vijay was the least sporty guy in class and, as an island boy, he couldn’t swim let alone dive. Cool watch they’d say, and then crack up laughing.

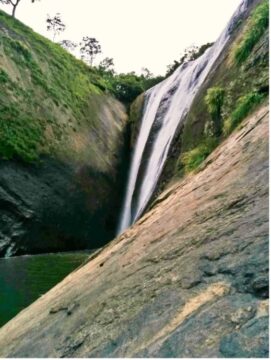

The school was in the mountains of South India, perched at a 2,000-metre altitude in a little town. People are often surprised when I mention that. Nobody seems to have heard of the Western Ghats. It was a little piece of paradise, sparsely populated at the time, with grassy knolls and ancient shola forests crowding the gorges. On weekends we’d go on hikes into the pristine wilderness, the likes of which I fear no longer exist.

Early that term, in September, H. decided to organise a hike to celebrate his eighteenth birthday. It may seem like an odd choice, but that’s the kind of place it was. A place where the coolest thing the most popular kid in class could do on his eighteenth birthday was to go hiking.

He invited a bunch of his friends, all guys. It was a motley crew, whom I knew superficially at best despite having lived with them for years. There was AZ, a sprinter who later went into private equity. His name was a sore point for me in elementary school because, for reasons that remain a mystery, teachers always had us lineup in alphabetical order by first name or reverse alphabetical order by last name. Then there was G., the second-best basketball player in our class, who later became a retail strategy guru. He had Dumbo-sized ears and the fact that he was born on April 1st didn’t make it easier to take him seriously. N., the student council president, went on to become a management consultant. He took up tenor sax in high school, learned a jazz tune, and then carried on like he was India’s Coltrane.

R. introduced us to billiards. He came from a well-known industrialist family, but from a minor branch—the Kimbal to Musk’s Elon. C. was a blessing because I got a share of the food he plied my roommate with as tokens of his affection. The TVs his father made brought comically animated Doordarshan renditions of the Ramanaya into homes across the nation, unwittingly creating a shared Hindu identity that laid the foundations for the modern BJP. T. played football. His family came from an offshoot of a royal family, and although his face more than defied the curse of inbreeding, his mind did not. R. ended up marrying his highschool sweetheart. Neither was especially good at marketing themselves at school, but they peaked at the right time–he as a marketer and she as a model. J. never said a word, so I didn’t know the first thing about him. M., as I discovered one year during class camp, was an endurance swimmer. He explained that he was from Chittagong where, during the monsoon, it was sink or swim. Counting H., Vijay was the eleventh member of this almost biblical troop.

Student-organised hikes required adult chaperones. If the hike was to be any fun, the key criteria for chaperone selection was benign neglect. You wanted someone who was physically present but mentally absent, satisfying the technical requirement without impinging on the tactical goal of freedom from adult supervision. The obvious choice was Mr. G., the science teacher, and Miss S., the choir instructor. They were recently engaged and, like the boys, were eager to break free. They had eyes only for each other.

The boys and the happy couple set out on their hike to Palar falls at five the next morning. That’s what we called it back then anyway—Palar falls—named after the dam it eventually emptied into, in the plains below. I hear it is now called Elephant Valley Falls, which is no less true and considerably more alluring, especially after what happened that day.

They straggled bleary-eyed into the cafeteria to pick up their packed breakfasts and lunches. Each came in a separate brown paper bag. Jam-and-butter and peanut butter-and-jam sandwiches for breakfast, with a hardboiled egg and apple. An egg salad and tomato sandwich for lunch, with an orange and cookie that never crumbled.

Stuffing the paper bags into their backpacks along with their bottled water, they set out. The hike to the falls was 30 kilometres downhill. If they raced, they could be there well before noon, giving them enough time for a swim and a picnic lunch. The way back was more arduous, but that’s what logging trucks covered with tarpaulin, tied with coir rope were for: to climb onto during uphill slogs.

I didn’t get out of bed until four hours later. It was Saturday and Annie had invited me to join her to visit Miss Wilson at Rosneath cottage, up by the radio tower. It was going to be a relaxing, fun-filled day feeding the turkeys, hunting for porcupine quills in the forest, and eating boiled chicken with mash and peas.

The boys must have been nearing the falls by the time Annie and I made it to Roseneath. The chaperones, diligent in their negligence, slinked off behind a boulder, out of sight and out of earshot. It was monsoon season and the streams were swollen. Water thundered over the ledge and down the falls, into the plunge pool. One of the boys had dropped by the off licence the previous evening. He fished a mickey of Old Monk from his backpack and passed it around. Some took a swig. Others, including Vijay, passed. There couldn’t have been enough rum in a mickey shared amongst almost a dozen boys for any of them to get drunk. But the collective act of rule-breaking was exhilarating, relaxing inhibitions and licensing more reckless behaviour than usual.

I picture them there. Some in swim trunks and others, too shy to be seen in their underpants, still in their jeans. They splash each other in the shallows. Then, giving up on staying dry, venture deeper and deeper. Now treading the water. Now swimming. The sky was overcast that day, and the water must have been cold. I see it: a chaotic black punctured by occasional swirls of navy green, blanketed by a heavy mist rising from the foot of the raging falls. The previous week’s rains had been heavy. The granite boulders surrounding the swimming hole were slick with damp. The pool was also deeper than usual, and its water more turbulent. A whirlpool had formed in the plunge pool at the base of the waterfall. Branches, leaves, and other forest detritus swirled around its vortex. Those in the water kept a respectful distance from it.

Different waterholes on our hikes had different traditions. At Tope we wore cutoffs with leather bum patches, so that we could glide more frictionlessly down the natural water slides. At Neptune’s Pool we sat on a ledge with our legs dangling in the water where itty-bitty fish nibbled at our feet. At Leving Stream we captured and imprisoned tadpoles which, to our great consternation, failed to metamorphose into frogs despite being securely sealed in glass containers. Looking at this list now, I realise how lucky we were. What we considered to be three waterhole traditions really are just pseudonyms for costly extravagances: water parks, ichthyotherapy, and paludariums. We took them for granted, maybe because our wilderness renditions didn’t carry a price tag. The same cannot be said for Palar falls.

At Palar, the tradition was to visit the cavern behind the falls. I remember it being a terrifying place. It was dark and dank and tiny, with enough space for only one person at a time. The crash of the water was deafening and the curtain of the falls that tumbled before you, seemingly impenetrable. You couldn’t hear your own thoughts. Didn’t trust your own feelings. It was just as well because all I really thought about was my impending mortality. And all I felt was the immense loneliness of it all. I don’t know why I was drawn to it, but we all were.

On any other day, you would swim through the falls to reach the cavern. That day the whirlpool forced the boys to make a detour, crawling crab-like along the pool wall to get there. Grabbing hold of the crevices between the boulders with their fingers and toes, they took turns making their way there and back, one after another.

An hour passed, by which time the boys were famished. Climbing out of the water, they dried off and fished their brown paper lunch bags out of their backpacks. It wasn’t until they started eating that someone noticed that Vijay wasn’t among them. They cast their eyes about, but he was nowhere in sight. They called out for him, but then realised that he wouldn’t be able to hear over the din of the water. The chaperones were still nowhere in sight so, half-eaten sandwiches in hand, they set out to look for him themselves.

They split up in the only two directions the gorge allowed. The upstream party returned empty handed. The downstream party found Mr. G. and Miss S., but no Vijay. Regrouping on the embankment, they looked at one another blankly. Then they turned almost in unison towards the whirlpool. I cannot imagine the horror they must have felt at that moment.

M., who was the strongest swimmer in the group, strode into the pool. K. followed at his heels, still clad in his sodden jeans. The chaperones, finally snapping to their senses, commanded them to stop. The only thing more calamitous than losing one child was losing more than one. It was quickly decided that Miss S. and two of the boys would stay put, in case Vijay had wandered off and decided to show up again. Everyone else was to run straight uphill towards the road, where they would hitch a ride to school and get help.

Annie and I got back from Roseneath to our dorm at around 5 o’clock. At 6, we heard the news that Vijay was missing. Dinner was a hushed affair. There was nothing that could be done immediately. The mountain paths were too dark and treacherous to navigate by night. A search and rescue mission was scheduled for the morning, along with an army dive team that had been mobilised from the plains.

They retrieved Vijay’s body from the whirlpool the next morning. I think about how it must have felt to die like that. Caught in a whirlpool, battered by branches, weighed down by too-big jeans, sucked into the cold, dark depths to a watery grave. It is too awful a fate to contemplate for anyone, let alone someone whose mind was ablaze. For me the thought, though terrifying, is abstract. Vijay was my classmate. He was brilliant, but I didn’t know him. Not really.

For his friends, though, things were less abstract. For H., whose birthday will forever coincide with Vijay’s death day, they were jarringly real. For reasons I will never understand, somebody thought it would be a good idea for him to accompany the dive team to the site of the accident. He was there when they hauled Vijay from the water, and he rode in the back of the jeep with him on his final trip up the mountain. Nobody had thought to bring a body bag. They covered Vijay’s head and torso as best they could with a towel, but his arms and legs stuck out. H. was inconsolable. He told me later about that ride up. Much of it was a blur, no doubt because of the trauma of it all. What he couldn’t shake from his memory, though, was the sight of Vijay’s limp arm with the watch on his wrist still ticking. For once there was truth in advertising.

The memorial service was the following weekend. I didn’t go. Girls weren’t invited. It was the second time in a week that I was relieved rather than indignant at our exclusion. Vijay’s father was there. So was his elder brother. I understand that they had taken the news matter of factly. They must have been gutted, but there was no outward display of emotion. No drama. Knowing what little I did of Vijay, that made sense. He had always carried himself with a quiet dignity. The apple didn’t fall far from the tree. He would have turned fifty this year, this guy I barely knew. I find myself thinking of him, wondering what would have become of him if he hadn’t put that damn watch to the test.