Rachel is one of the winners of the American Philosophical Association’s 2025 Public Philosophy Op-Ed Contest for one of her essays here at 3QD. There is more information about that and other APA prizes at their website:

The APA committee on public philosophy sponsors the Public Philosophy Op-Ed Contest for the best opinion-editorials published by philosophers. The goal is to honor up to five standout pieces that successfully blend philosophical argumentation with an op-ed writing style. Winning submissions will call public attention, either directly or indirectly, to the value of philosophical thinking. The pieces will be judged in terms of their success as examples of public philosophy, and should be accessible to the general public, focused on important topics of public concern, and characterized by sound reasoning.

Rachel Robison-Greene (Utah State)

“The Temptations of Nostalgia” (3 Quarks Daily)

Rachel Robison-Greene earned her PhD from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in 2017. Her research interests are largely in meta-ethics, epistemology, and applied ethics (with particular interests in animals, the environment, and technology). She is the author of the book Edibility and in Vitro Meat: Ethical Considerations. She is a regular contributor to the popular blog 3 Quarks Daily. Rachel serves as the Secretary of the Culture and Animals Foundation and is the Chair Elect of the Intercollegiate Ethics Bowl.

More information about the APA prizes here.

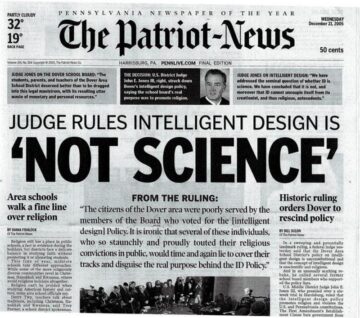

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking.

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking. Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

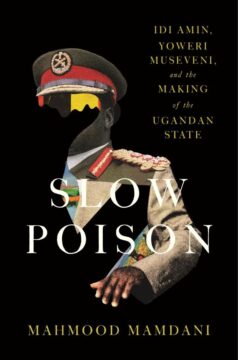

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.