by Charles Siegel

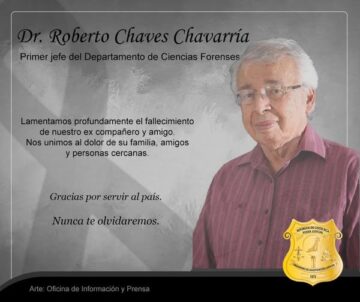

Last week I learned of the recent death of Roberto Chaves Chavarria, of San José, Costa Rica, aged 90. His work benefited thousands upon thousands of his countrymen, and many thousands in other countries as well, who will never know his name. And he had a profound effect on my career as a lawyer, and on the direction of my life as a whole.

Chaves was a forensic toxicologist, and the first head of the Department of Forensic Sciences, an office in the Costa Rican “Poder Judicial,” or judicial branch. In the Costa Rican legal system, as in that of most Latin American countries, judges and other judicial officers often conduct their own factual investigations into cases before them.

In the late 1970s, Chaves learned of a large group of workers, on a banana plantation near the small town of Rio Frio, who were sterile. Over the course of many investigative trips, he interviewed workers and their wives, plantation managers, doctors and others. Chaves eventually concluded that the men had been sterilized through contact with a pesticide they applied to the roots of the banana plants. This pesticide, known as “DBCP,” was used to kill worms that infested the soil beneath the plants.

DBCP was invented by scientists at Shell Chemical Co., a subsidiary of the oil giant, and originally tested on pineapple plants in Hawaii. It proved to be very effective, and was used on pineapple and banana plantations around the world. DBCP-based pesticides were manufactured by several American companies, including Dow Chemical and Occidental Chemical as well as Shell.

The cluster of sterile banana workers that Chaves discovered in Rio Frio was not the first such group. A few years earlier, men who worked in the Occidental factory making the stuff in Lathrop, California, had also been found to be sterile. This eventually led to a ban on DBCP use in the United States, but Dow and another smaller company continued to sell it overseas.

Meanwhile, Chaves continued his work in Costa Rica, and learned about the American developments. Read more »

The recent show

The recent show  Sughra Raza. Landings, Dec 23, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Landings, Dec 23, 2025.

At the end of each of the past twelve years I have written a long rhyming ballad, reviewing the period coming to a close, giving thanks for some events and lamenting others. I began in December 2013, while I was recovering from a lengthy illness; and I recited what would be the first of a series at a family New Year’s Eve party, among some of those whose support had been indispensable to the recrudescence of my health, and to whom I therefore wished to express my gratitude.

At the end of each of the past twelve years I have written a long rhyming ballad, reviewing the period coming to a close, giving thanks for some events and lamenting others. I began in December 2013, while I was recovering from a lengthy illness; and I recited what would be the first of a series at a family New Year’s Eve party, among some of those whose support had been indispensable to the recrudescence of my health, and to whom I therefore wished to express my gratitude.

Let’s grant, for the sake of argument, the relatively short-range ambition that organizes much of rhetoric about artificial intelligence. That ambition is called artificial general intelligence (AGI), understood as the point at which machines can perform most economically productive cognitive tasks better than most humans. The exact timeline when we will reach AGI is contested, and some serious researchers think AGI is improperly defined. But these debates are not all that relevant because we don’t need full-blown AGI for the social consequences to arrive. You need only technology that is good enough, cheap enough, and widely deployable across the activities we currently pay people to do.

Let’s grant, for the sake of argument, the relatively short-range ambition that organizes much of rhetoric about artificial intelligence. That ambition is called artificial general intelligence (AGI), understood as the point at which machines can perform most economically productive cognitive tasks better than most humans. The exact timeline when we will reach AGI is contested, and some serious researchers think AGI is improperly defined. But these debates are not all that relevant because we don’t need full-blown AGI for the social consequences to arrive. You need only technology that is good enough, cheap enough, and widely deployable across the activities we currently pay people to do.