by Philip Graham

A conversation between Christine Sneed and Philip Graham

Since 2010 Christine Sneed, winner of the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction (among other awards), has published six acclaimed books: the story collections Portraits of a Few People I’ve Made Cry, The Virginity of Famous Men, and Direct Sunlight, and the novels Little Known Facts, Paris, He Said, and Please Be Advised: A Novel in Memos. With each new book Sneed has expanded her impressive range of vision, combining cultural insight with the everyday strangeness of her fictional characters.

Since 2010 Christine Sneed, winner of the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction (among other awards), has published six acclaimed books: the story collections Portraits of a Few People I’ve Made Cry, The Virginity of Famous Men, and Direct Sunlight, and the novels Little Known Facts, Paris, He Said, and Please Be Advised: A Novel in Memos. With each new book Sneed has expanded her impressive range of vision, combining cultural insight with the everyday strangeness of her fictional characters.

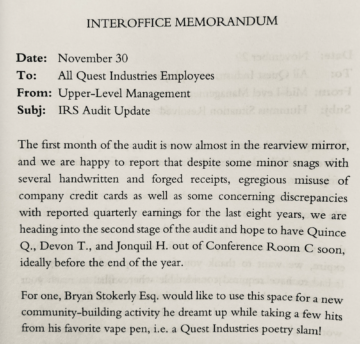

Having explored in her novels the subtle and not-so-subtle mechanics of craft and inspiration in the art world, or the corrosive effects of Hollywood fame on an actor and his family, Sneed has recently set her sights on the contradictions of American capitalism. Please Be Advised is a deliciously droll novel (told entirely through the surprisingly illuminating lens of interoffice memos) that takes the reader on a journey through successive rings of corporate hell.

Philip Graham: Pleased Be Advised stunned me when I first began reading it—the novel is a wild and hilarious romp that’s entirely presented through the office memos of a struggling company named Quest Industries, which makes “collapsable office products” of dubious utility. Your earlier work, both short stories and novels, are quieter, even contemplative, and incisive in their paring away of your characters’ illusions and presentations of self. Those memos of Please Be Advised are laugh-out-loud funny on nearly every page. And yet, as I read further, I remembered that your earlier novels also made use of various documents to arrive at a deeper level: an artist’s sketchbook, a secret diary, obituaries, a character’s attempted memoir.

Philip Graham: Pleased Be Advised stunned me when I first began reading it—the novel is a wild and hilarious romp that’s entirely presented through the office memos of a struggling company named Quest Industries, which makes “collapsable office products” of dubious utility. Your earlier work, both short stories and novels, are quieter, even contemplative, and incisive in their paring away of your characters’ illusions and presentations of self. Those memos of Please Be Advised are laugh-out-loud funny on nearly every page. And yet, as I read further, I remembered that your earlier novels also made use of various documents to arrive at a deeper level: an artist’s sketchbook, a secret diary, obituaries, a character’s attempted memoir.

Christine Sneed: Hybrid forms have long been of interest to me as both a reader and a writer. When I started writing seriously in the early 1990s, it was poetry, not fiction, that I was attempting to put on the page. I did try to write a few short stories too, but it was clear I wasn’t ready—as with acting, the artifice must not be visible in fiction-writing, and everything I initially wrote was awkward and mannered. The compression and playfulness of a poem seemed both a challenge and an invitation. The short lines I was working with and the sensory imagery and concrete detail helped me focus on language, and as I got a little older and read more widely, I started to write fiction with more confidence. This was after earning my MFA in poetry. By that time, I had a better sense of how to create a character that seemed real and was not simply my surrogate.

The playfulness of hybrid and found forms like the memo or the resume or diary entry offer a chance for me to return, I suppose, to the compression of a poem. When I was writing Please Be Advised, it was great fun to begin every new memo, and to write in a different character’s voice. It was a bit like writing comedic prose poetry.

PG: That’s a wonderfully apt term, “comedic prose poetry”! Most of the chapters—they’re labeled “Interoffice Memorandums”–in Please Be Advised are a page or two long, and rarely over three. They’re dated, arrive at the pace of one every day or so, and at least at the beginning of the novel they come from Upper, Mid- or Lower-Level Management (though each level’s missives seem equally petty and invasive). Occasionally the company’s president, Brian Stokerly, Esq., weighs in with memos titled “Important Epiphanies,” intended for the benefit of his employees. His insights arrive in clusters, such as “Making monkey sounds can be great fun, but as a rule should not be done while riding mass transit,” followed by “Dill pickles have no calories! I know this seems unbelievable, but I’m not lying.” Lucky for him he has a captive audience.

CS: Bryan Stokerly was one of my two favorite characters to write memos for (the other is office manager/disgraced coroner Ken Crickshaw Jr.). Bryan’s extreme narcissism and obliviousness to how his highhanded behavior is interpreted by his employees were good tools to have at my disposal. I could work hyperboles and complete nonsense into his memos and it was incredibly fun—and hardly a stretch from what does happen in some corporate workplaces. I used to teach a business-writing course and we’d look at actual corporate office memos which had been leaked by disgruntled employees, and it was both hilarious and disturbing that their authors had no clue how to communicate with their staff.

Having worked in a corporate office for two years directly after I graduated from college in Chicago’s Loop (Quest Industries is set in that office, although the characters aren’t based directly on anyone I worked with), I learned a lot about the human animal in captivity—much of it unflattering (I’m not exempting myself, either, that’s for sure). It became to me clear pretty quickly that I needed to find a different way to spend my life.

No workplace is ideal, needless to say, but my experience of the corporate office was more confounding and draining than the other workplaces I’ve been a part of. The income inequality, for one, is usually glaringly obvious. I made $22,000 a year at that job. The higher ups were doubtless earning six figures. Of course my job description was different from the president’s, but I was still spending as many hours a day of my never-to-be-repeated life at my desk as he and most everyone else was. You understand pretty quickly what Noam Chomsky meant when he said that using an hourly wage to measure the value of a human life is inherently unfair, and let’s be honest, depraved, if not also evil.

PG: Speaking of being depraved, I’m reminded of recent studies suggesting that up to 21% of people in the upper levels of the corporate world can be considered psychopaths. I’d peg President Stokerly in that category, based on his memos. And you make such fruitful use of this underappreciated literary genre, the memo. It’s like an unwitting confessional mode, and an ideal way to reveal the odd corners of a character.

As the novel progressed, I began to wonder, Who are the poor souls who have to read these things? What do they make of Mid-Level Management’s December 6 memo, “Secret Santa Protocols,” which decrees that the “longstanding $5 maximum per day/gift has been raised to $5.32, which we believe is a fair adjustment for inflation”? But then, given Stokerly’s mandate that employees start submitting little essays titled “My Story of Personal Triumph,” we get a window into their lives (and, eventually, their candy-eating habits).

CS: “[R]ecent studies [suggest] that up to 21% of people in the upper levels of the corporate world can be considered psychopaths.” I had never heard that before, but I can’t say I’m surprised. CEOs of Fortune 500 companies are not known for being altruistic, sympathetic people who want everyone to have a fair share of the pie.

As for Bryan Stokerly, you’re right—he’s very much meant to come across as a charming psychopath. Or maybe a sociopath. I don’t think he’d murder anyone himself, but I could imagine him hiring a hitman to off an enemy—if he were ever sober enough to form a coherent, albeit criminal, thought.

The “Stories of Personal Triumph,” were for sure a way to bring in more characters and they were probably my favorite memos to write. I never really knew what story each employee was going to tell. I’d usually start with a title and take it from there.

The “Stories of Personal Triumph,” were for sure a way to bring in more characters and they were probably my favorite memos to write. I never really knew what story each employee was going to tell. I’d usually start with a title and take it from there.

PG: Those “Triumph” stories are so embarrassingly revealing, as if having the opportunity to shed for a moment their corporate anonymity opens a floodgate of Too Much Information. These memos are funny and sad, while the management memos are funny and infuriating. I think that one of the achievements of the novel is how you manage to induce both laughter and outrage at the same time from a reader. Please Be Advised is great fun to read, while its deeper message seeps into you, a despair that the details of this workplace, even when leaning into the absurd (the Company Limerick Contest!), are uncomfortably close to the 9-5 reality that most people in the country experience.

Meanwhile, the impending IRS audit more than sets the plot in motion . . .

CS: I love how you describe the Stories of Personal Triumph as “funny and sad, while the management memos are funny and infuriating.” This is exactly what I was aiming for! I’d probably written about 10 memos when I began to wonder if they might form the basis of a novel. After I’d committed to turning this motley assortment of memos into this form, I recognized that it might be a good idea to write it as a poly-vocal story. The Stories of Personal Triumph subsequently allowed me to dedicate at least one memo each to characters who weren’t in a starring role (although the stars did get their stories of personal triumph too—the Christopher Walken story that Ken Crickshaw Jr. tells is the one I think I had the most fun writing).

One of my other objectives with the SoPTs, something I didn’t recognize until I’d written several of them, was to bring in more of each character’s life outside of the office, i.e. these memos permitted me to bring each of these employees more fully into view. Hence the male stripper story told by Brenda Priebus, the “garage-sailing” hobby Ginny Snell cops to, and Hal Hanson’s “star turn” as a film extra.

As for the IRS audit, you nailed it, it was for sure meant to thicken the plot. It was highly enjoyable to write too. The fact that the person who made the prank call to the IRS is one of the people at Quest who most hated the audit—if not the person who hated it most . . . poetic justice? It was my attempt, I think now, at an O. Henry-like twist.

PG: A delicious irony of that twist is the person who made the prank call was so drunk at the time they probably can’t remember making it.

That IRS audit really begins to unravel the company, doesn’t it? There’s the invasive candy-eating policy, and the even more invasive (and hilarious) enforcing of that policy (“On Wednesday at 2:20 PM, Fred Saben was spotted eating a Twixt bar, peanut butter variety, in the doorway of his office,” etc). And then there is the unasked-for installation of 30 treadmill desks, the proposed daily mental health activities (“Monday—combatting ennui”), and the compiling of the very low bar Employee Cookbook (such as the quite short recipe for how to prepare orange slices). Activities, rules, and surveillance, all in the face of impending company chaos.

That IRS audit really begins to unravel the company, doesn’t it? There’s the invasive candy-eating policy, and the even more invasive (and hilarious) enforcing of that policy (“On Wednesday at 2:20 PM, Fred Saben was spotted eating a Twixt bar, peanut butter variety, in the doorway of his office,” etc). And then there is the unasked-for installation of 30 treadmill desks, the proposed daily mental health activities (“Monday—combatting ennui”), and the compiling of the very low bar Employee Cookbook (such as the quite short recipe for how to prepare orange slices). Activities, rules, and surveillance, all in the face of impending company chaos.

CS: It did seem an ironic truism that Quest’s upper level managers would become obsessive about imposing petty rules and trying to maintain order in the office when much bigger problems were what needed their attention. I did, however, eat too much candy when I worked at office jobs—it helped make the ennui bearable! (It probably would have been good if we’d had an anti-candy policy in a couple of my workplaces, but maybe not one quite as draconian as Quest’s.)

It seemed to me too that there was no better candidate than the IRS to come in to add dramatic tension (such as it is in satire) since an audit by nature is designed to rip the roof off of a place, and I could also bring in the auditors as supporting characters, which was very enjoyable.

It seemed to me too that there was no better candidate than the IRS to come in to add dramatic tension (such as it is in satire) since an audit by nature is designed to rip the roof off of a place, and I could also bring in the auditors as supporting characters, which was very enjoyable.

PG: And adding to the company’s miseries are the multiple injury lawsuits resulting from one of Quest Industries’ most poorly designed products: the collapsible paper cutter. One of the great pleasures of reading Please Be Advised is that the seemingly narrow perimeters of an office memo inexorably fan out into a wider world of corporate disfunction, casual cruelty, despair, incompetence, and absurdity. Yet somehow the spirit of comedy reigns over it all. The humor, whether bitter, goofy, or simply head-shakingly hilarious, is always incisive and revealing. Laughter as cultural critique.

This is an important novel, especially for these times when the American model of capitalism is fraying before our eyes, whether through rising inequality, or employees preferring to work from home rather than submit to a toxic workplace, or corporations increasingly treating customers as rubes, marks, or simply as the enemy. When Quest Industries company president Bryan Stokerly, Esq. wins the Employee of the Year Award, “a nine-day vacation for two at a luxury resort on Maui” while the runners-up receive “a Subway gift card for $20 and a coupon for a free bottle of Newman’s Own salad dressing,” laughter also serves as bitter revelation. Brilliant.

This is an important novel, especially for these times when the American model of capitalism is fraying before our eyes, whether through rising inequality, or employees preferring to work from home rather than submit to a toxic workplace, or corporations increasingly treating customers as rubes, marks, or simply as the enemy. When Quest Industries company president Bryan Stokerly, Esq. wins the Employee of the Year Award, “a nine-day vacation for two at a luxury resort on Maui” while the runners-up receive “a Subway gift card for $20 and a coupon for a free bottle of Newman’s Own salad dressing,” laughter also serves as bitter revelation. Brilliant.

CS: Thank you for reading Please Be Advised exactly as I hoped anyone who picked it up would. As is doubtless clear, I find so many aspects of corporate culture worthy of both parody and redress. Greed has always made me furious (and it’s only getting worse, needless to say—a 12-pack of Pepsi for $10.99?!). Our culture elevates CEOs into cultish figures and promulgates the belief that if someone is rich or good at making money, they are worthy of slavish reverence.

Quest’s CEO Bryan Stokerly is certainly meant to reveal the folly of the above, being an absurdly incompetent businessman and an unapologetic drunk who, if he hadn’t been permanently barred from his favorite English football club’s stadium (Arsenal FC), would have stayed in England and led a quietly unproductive life, rather than bilking Quest Industries of millions and generally ruining everything he touched.

While writing Please Be Advised, I remembered the various office jobs I’ve worked since high school and feel fondness for those years (but would not want to relive them)! That M-F schedule was hard, and the work was often dull. I knew I wasn’t alone in feeling this way, but I wanted to write about it in a way that might make people laugh, even as they nodded in recognition.

***

Christine Sneed is the author of three novels and three story collections, most recently Please Be Advised: A Novel in Memos and Direct Sunlight: Stories. She is the editor of the short fiction anthology Love in the Time of Time’s Up, and her work has appeared in publications including Ploughshares, New England Review, The Best American Short Stories, and O. Henry Prize Stories. She has received the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction, Ploughshares‘ Zacharis Award, and the Chicago Writers’ Association Book of the Year Award, among other honors. She lives in Pasadena, California.

Philip Graham is the author of eight books of fiction and nonfiction, including The Art of the Knock: Stories, The Moon, Come to Earth: Dispatches from Lisbon, and (as Author Unseen) the novel What the Dead Can Say. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Washington Post Magazine, Paris Review and elsewhere. A co-founder of the literary/arts journal Ninth Letter, he is currently the Editor-at-large for the journal’s website.