by Peter Topolewski

Before the violence in the movie Bugonia moves center screen—and the narrative takes a not completely unexpected left turn—it’s made clear Teddy’s paranoia and consuming conspiracism and violent nature all have roots in childhood trauma. Things like child molestation and the hospitalization of his drug addled mother.

Oh gawd, you think, another movie explaining away awful behavior with a hellish upbringing. Seen it a million times, it’s boring already.

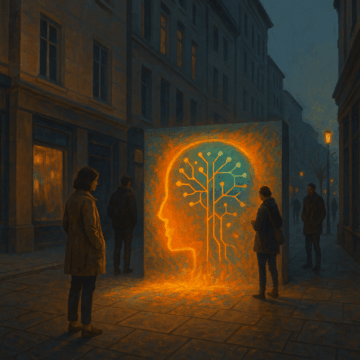

Boring in a movie, maybe, but that’s real life. Except it’s not only trauma that explains rotten behavior. Everything up to this moment in time explains everything about you, everything you’ve done, you’re about to do, and ever will do. This according to Robert Sapolsky, neuroscientist and author of Determined. You have no free will, your actions are determined by your genes, your environment, and your experiences. You have control over none of them.

His book, a couple years old now, has been well reviewed and discussed right here on 3 Quarks Daily, and there’s no need to do so again. The book feels like a mess at times, but an enjoyable one. And the choices—yes choices—Sapolsky made while writing the book are fascinating, the details of the science both enlightening and staggering, his purpose for writing it never more vital. And the implications are a trip. There’s no reason to carry on with this, but I have no choice but to go on, no more choice than I had to stop reading Determined, no more choice than Sapolsky had writing it.

Did he write it? Read more »

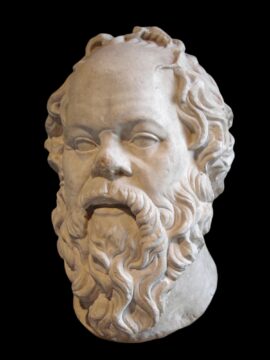

When I turned fifty, I went through the usual crisis of facing that my life was—so to speak—more than half drunk. After moping a while, one of the more productive things I started to do was to write letters to people living and dead, people known to me and unknown, sometimes people who simply caught my eye on the street, sometimes even animals or plants. Except in rare cases, I haven’t sent the letters or shown them to anyone.

When I turned fifty, I went through the usual crisis of facing that my life was—so to speak—more than half drunk. After moping a while, one of the more productive things I started to do was to write letters to people living and dead, people known to me and unknown, sometimes people who simply caught my eye on the street, sometimes even animals or plants. Except in rare cases, I haven’t sent the letters or shown them to anyone.

Sughra Raza. First Snow. Dec 14, 2025.

Sughra Raza. First Snow. Dec 14, 2025. One Monday in 1883 Southeast Asia woke to “the firing of heavy guns” heard from Batavia to Alice Springs to Singapore, and maybe as far as Mauritius, near Africa.

One Monday in 1883 Southeast Asia woke to “the firing of heavy guns” heard from Batavia to Alice Springs to Singapore, and maybe as far as Mauritius, near Africa.