by Leanne Ogasawara

Which do you think is worse: a scenario in which every single email you ever wrote, (including all the drafts) and every last photo and video you ever took, are stored on the cloud for eternity. This is made publicly available, and is used to construct a book about your life.

OR

You destroy all trace of yourself in the digital record, and still a novelist uses your life as fodder for material, attributing thoughts and experiences to you, using your real name in the story, relating things that never happened.

1.

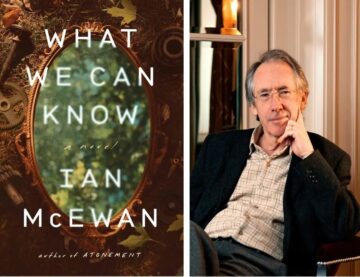

Set one hundred years in the future, the world depicted in Ian McEwen’s new novel, What We Can Know, is a very different one from our own. War and climate disaster have reshaped everything (surprise, surprise). The oceans have risen, and England is now an archipelago. Meanwhile, North America is ravaged by warlords and gangs, and China’s thirty-year experiment with democracy is collapsing amidst the people’s growing desire to wage war on Nigeria, a country which is now the sole remaining superpower and the only place which has managed to keep the lights on.

In England, people mainly eat protein bars and drink acorn coffee. The population has been halved. It’s not such a dire place when the story opens. It’s just harsher, with daily life more constrained. And not surprisingly people look back with longing—and also fury—to the people of our day.

We had so much. Oceans filled with fish and all those vineyards producing delectable wines. In the Age of Derangement, a term borrowed from Amitav Ghosh, why was our relentless avarice allowed to ravage the world unchecked?

One thing that has not changed over the hundred years separating our time with theirs is the human predilection for love and obsession.

Take the novel’s protagonist. Thomas Metcalfe is an academic in the Humanities—a field which has somehow survived to the year 2119, but only barely. Professors are sharing seven to a bathroom and there is no money. And yet, that does not stop Metcalfe from devoting himself to unraveling a certain poem by the poet Francis Blundy. Despite not having access to the work itself, he knows from the massive amounts of data that it did once exist and that it was read aloud by the poet at a legendary dinner party that occurred in 2014, when Blundy, one of the most renowned writers of the time, recited from memory what was a love poem for his wife.

McEwan says he was inspired to write this novel after his own reading of a John Fuller poem called “Marston Meadows: A Corona for Prue,” saying he knew he had to write a novel about it as soon as he read it. Read more »