by David Kordahl

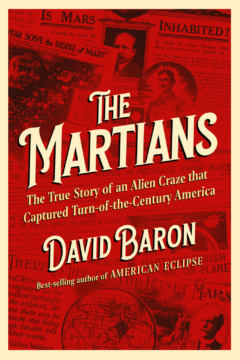

This article is a lightly edited transcript of a conversation with David Baron about his new book, The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America. A video of this conversation is embedded below.

Intro and Percival Lowell Background (0:00)

Origins of the Canal Craze (6:39)

Gathering Evidence for the Canals (10:41)

Scientific Debate with Astronomers (14:02)

Thinking about “Outsider Scientists” (23:35)

Influence of Canals on Culture (27:45)

Reflections on Mars and the Future (32:33)

Intro and Percival Lowell Background

Today I’m speaking with David Baron, a seasoned science writer who has contributed to many major American journalism outlets, including the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal. He was a longtime science correspondent for NPR, and his TED Talk on the experience of solar eclipses has been viewed millions of times. His last book, American Eclipse, won the American Institute of Physics Science Writing Award in 2018. Today we’ll be discussing his new book, The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America.

The “alien craze” in the subtitle of your book is the story of how, for about a decade at the beginning of the twentieth century, many people came to believe that the planet Mars held not only life, but a complex civilization. The person most responsible for popularizing this view as an established scientific fact was Percival Lowell. Lowell functions as a main character in your book.

I want to thank you for joining me today. At what point in your reporting for this book did it become clear that Lowell would function as a central figure in your story?

Oh, pretty much I knew that from the start. I first learned about the so-called “canals on Mars” from Carl Sagan, when I was in high school and watched the Cosmos series on PBS. On an episode about Mars, Sagan talked about this astronomer, Percival Lowell, who at the turn of the last century saw these weird lines on Mars that he believed were irrigation canals. It’s remembered as one of the great blunders in science, because it was an idea that really took off.

What actually surprised me was not that Lowell was my main character, but just how many other people got swept up in this craze—some of them quite prominent, famous scientists and inventors who totally believed that in fact there was the civilization on Mars. It was not just Percival Lowell. It was quite a collection of interesting characters.

That’s true. You are yourself somewhat of a character in the book. You go to visit many archives around the world to do reporting for this. One of the things that I found compelling about your portrait of Lowell was just how complex a figure he turns out to be. He’s born into this Boston Brahmin family. He’s got a brother who becomes the president of Harvard. His sister is Amy Lowell, who I think I remember reading in high school.

She was a famous poet.

Yeah. And wasn’t Percival Lowell himself a major public intellectual before he even got into the astronomy business? I’m curious to hear how your view of him evolved during the project. There are times where you want to poke fun at him, but you say at one point, he was “a young man who wanted for nothing, who could do anything. Yet, as I delved into his background, I came to appreciate the prison he inhabited. For the scion of a famous lineage, the expectations weighed mightily.”

He was a fascinating character and came from a truly prominent family. The Lowells of Massachusetts made their fortune in textiles back in the early 1800s, at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. The city of Lowell, Massachusetts, is named after the Lowells. Percival Lowell was born into this family where much was expected. James Russell Lowell, the founding editor of the Atlantic Monthly, was a cousin. The Lowells were philanthropic. They gave a lot of money to Harvard. They helped in the founding of MIT. When Lowell graduated from Harvard in 1876, he could do anything he wanted with his life.

And at first, what he wanted to do was to travel. He spent a lot of time in the Far East, in Japan and in Korea, back when Asia was seen as this extremely exotic, otherworldly place. And he was sort of a roving anthropologist. He wrote about Asian cultures in best-selling books and articles.

When he read about the possibility of life on Mars, it was, I think, that same interest in other beings and other cultures that turned him to astronomy when he was about the age of forty. When I went into writing this book, I knew the basics of the story and how history kind of laughs at Percival Lowell as someone who made this huge mistake in science. But I came to have more empathy for him.

I actually think his theory about these canals on Mars was not crazy when he first proposed it in 1894. It was a little out there, but it was a coherent theory that explained these weird features being seen on Mars. It was not insane to think there could be life on Mars, maybe civilized life on Mars.

On the other hand, Percival Lowell had a huge ego, and I think a fragile ego, and could not accept any criticism of his theory. And the more people criticized it over time, the more he dug in his heels. And by the time he died in 1916, he was portraying himself as a persecuted genius who was not believed, but who someday would be seen as having been correct. He almost saw himself as the next Charles Darwin—a person of that importance.

So it’s a sad story in the end, but actually, he did a lot of good. He really inspired people to imagine life in outer space and helped to inspire science fiction and even the early space scientists. So he did a lot of good as well as making a huge mistake.

Origins of the Canal Craze

One of the things I liked about the way you set up the story was that you really do show that Lowell was not the first guy to have this idea of life on Mars. You talk about how there was a 100,000-franc “prize to the first astronomer, French or foreign, who … shall be able to communicate with any planet or star.” You discuss at some length the French author Camille Flammarion, who promoted such ideas in the early 1860s in magazine articles and books like The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds. You also talk about Giovanni Schiaparelli, who had these quite beautiful drawings of the “canali” of Mars, which you point out means “channels,” but was mistranslated. How would you characterize the sentiment of the public towards Mars before Lowell got there? He comes in kind of at the beginning of the twentieth century, but the public was sort of primed to take him seriously, right?

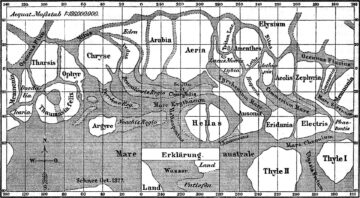

Right. So as you said, this whole idea of canals on Mars started with Giovanni Schiaparelli, who was a prominent astronomer in Milan, Italy, and it was in 1877 that he set out to make a detailed map of Mars. He was the one who first reported this network of fine, extremely straight lines on Mars that he imagined were waterways of some sort. As you say, he called them “canali,” which in Italian means “channels,” but was mistranslated into English as “canals.” Some people who talk about the canals on Mars will say, “Oh, of course it was all just due to mistranslation.” But that oversimplifies it. Yes, there was a mistranslation, but people knew it was a mistranslation, and it was sort of a joke for a while that there were canals on Mars. But that was the name given to these lines.

It was Lowell in 1894 who then proposed that they really were canals—not for navigation, but for irrigation. That fit in with the idea that Mars was an older planet than Earth. And Lowell said it was running out of water. And indeed it is. You know, billions of years ago, Mars did have water flowing on its surface. It has run out of water. Well, Lowell didn’t know that, but he assumed that that was the case, and so if there was a civilization on Mars, and if Mars was running out of water, then the most important thing for the people of Mars would be to find a way to live on a drying, a dying planet. And that meant tapping the melt water from the polar ice caps and bringing it down to their farms.

Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1877 talked about the canals on Mars. People started thinking about maybe there was a civilization there. Camille Flammarion—this great, influential astronomer in France—believed there was life on Mars. So the idea was out there. And then even when Lowell came along in 1894, it still was seen as an interesting theory and kind of a joke. But by the beginning of the twentieth century, it came to be taken quite seriously, to the point that in 1906, the New York Times was declaring there is intelligent life on Mars. In 1907, The Wall Street Journal, one of the most serious newspapers in America, said that the biggest news of the year was the proof of intelligent life on Mars.

So it went from sort of a frivolous idea to an interesting scientific theory to an almost accepted fact before the first decade of the twentieth century was done.

Gathering Evidence for the Canals

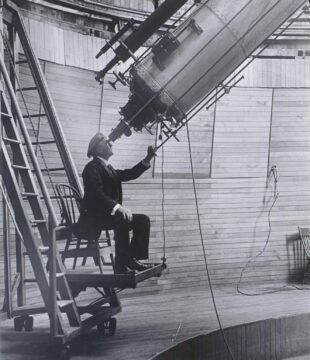

As a man in my late thirties myself, I took some comfort in reading how Lowell was about this age when he took up astronomy. And it is quite remarkable how in 1893 he reads one of these books by Flammarion, and a few years later, he’s already building an observatory near Flagstaff, Arizona, to make observations for himself. It seems like a daunting project for a public intellectual who becomes interested in a scientific project to use his own funds to make a new facility to investigate things for himself. What conditions allowed Lowell to be able to pursue that?

Well of course he had very deep pockets. That was a big help. As I said before, he graduated from Harvard. His family was very much involved in Harvard in terms of serving on various committees overseeing parts of the university. Lowell was involved with the astronomy department at Harvard. Even though he had taken science courses as an undergraduate, he did not have advanced training in science. But he thought of himself as someone educated in science, and he was to some extent.

I should say—and I point this out in the book—the idea for the observatory in Arizona was not originally his. It was an astronomer at Harvard, William Pickering, who was an acquaintance of his. Pickering had the idea that in 1894, when Mars and Earth were going to come especially close to each other, he wanted to set up a temporary observatory in Arizona to take advantage of the clear air there to study Mars. But Pickering could not find the funds for it, and he was an acquaintance of Lowell’s.

Lowell thought it was a great idea. But if Lowell was going to provide the funds, he wanted to be in charge. So he hired William Pickering from Harvard for a time to help establish the observatory. So the observatory was established in Flagstaff. It’s still there. The Lowell Observatory continues to do good work and scientific outreach. Anyone who goes through Flagstaff should visit.

So Lowell took this idea and hired a couple of people from Harvard to help establish the observatory and used his own funds to buy one of the finest telescopes of the era and have it installed in Flagstaff. It was not unheard of at the time for amateurs to get involved in astronomy and to do important work—far from it, in fact. There were quite a few folks who had been lawyers or doctors or merchants who later in life used some of their free time to study the stars. So Lowell was following in their footsteps, but he had the funds to really do it in a grandiose way.

Scientific Debate with Astronomers

Now, as I understand it, someone like Flammarion was never quite as insistent about the canals being proof positive of a culture on Mars the way that Lowell was, but, as you referred to earlier, Lowell had a background as an interpreter of Eastern cultures for Westerners. He was writing articles and books about these sorts of things. I guess one interpretation is that he was primed psychologically to look for some sort of culture out in space, the way that maybe someone who was only trained in the sciences may not have. It was interesting to me that there was quite a bit of contentious evidence, even at that time, that this could have been a psychological projection.

I guess I should give a spoiler alert.

There are not canals on Mars.

There never were canals on Mars.

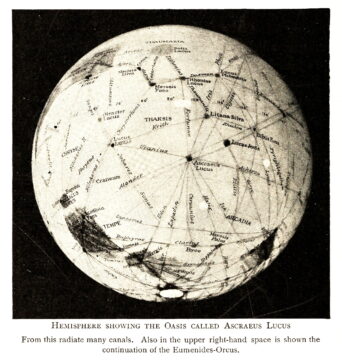

The way the story is remembered is as an optical illusion that fooled a whole generation. That, indeed, these exceptionally straight lines crisscrossing the planet that Lowell saw, that Flammarion saw, that Schiaparelli saw—were never there. In the end, the best explanation is that people were studying Mars through telescopes, and looking through the Earth’s atmosphere made perceiving the surface of Mars a very difficult thing to do. You could make out shapes, but you couldn’t make out the details. And so the human eye, seeing things at the very limit of perception, tended to see patterns where there weren’t any.

Even at the time, this was being proposed as a hypothesis. Not everyone saw the lines on Mars. And so there were a few astronomers, one being Walter Maunder, who was at the Greenwich Observatory in England, who was an expert on sunspots. Sunspots are these dark little freckles that you can see on the Sun if you look at the sun through an appropriate filter. He found that sometimes these little dots on the Sun could look like lines, even though they weren’t lines.

And so he had the idea, well, maybe the same thing’s happening on Mars. And he was pushing this idea for quite a while, to the point where he conducted a really interesting study in 1903, where he enlisted a whole bunch of young schoolboys at a Greenwich school to draw what they saw when they were shown a map of Mars where the lines were erased and instead more naturalistic features were put in. When the boys drew this, they were seated 20 or 30 feet away, and they couldn’t quite make out what was there. Even though there were no lines on this drawing of Mars, and they didn’t know what they were drawing, they drew lines.

So it was possible to trick the human eye to see lines where there weren’t any. That wasn’t proof that that was what was happening on Mars. It was just the possibility that that was happening.

In fact, the astronomical community was divided into two warring camps that were really at each other’s throats: the “canalists” and the “anti-canalists.” Lowell was the clear leader of the canalist faction. Maunder and a few others were leading the anti-canalists.

An interesting thing your book highlights is that even though now we don’t think there are canals on Mars, a lot of good things came out of Lowell’s drive to prove that there were. For one thing, they were taking photographs through their telescopes, which was sort of new. For another thing, they were organizing international expeditions to both Africa and South America to find better locations to take these photographs. In a way, it does seem like that sort of presages the more internationalist approach to science that we appreciate today.

Yeah. I think this is a particularly sensationalistic and interesting case of science, which is why I wrote a book about it, but this is how science works, right? You find something inexplicable and then you come up with theories to explain it, and then you get the evidence to try to prove or disprove whether the hypothesis is correct. And so while Lowell’s theory that the lines on Mars were due to an advanced civilization having built a canal network on Mars to irrigate their crops was wrong in the end, that was a theory to be tested. And so people had to go out and find ways to test that. And that’s good, in terms of pushing science forward to try to explain something that’s a mystery.

Lowell went to North Africa with the idea he might move his telescope there. He didn’t. But what I think is kind of the climax of the book is just insane in retrospect.

In 1907, in an attempt to prove beyond any doubt that the canals were there, Lowell, having developed some new techniques of photography to be able to actually take photographs of Mars through a telescope, funded just a Herculean expedition to South America. He hired an astronomer from Amherst College who also thought that the canals might be there to disassemble the seven-ton monster telescope at Amherst College in Massachusetts, to pack it into 119 boxes, put it on a ship from New York to Panama, take it across the isthmus by train because the canal wasn’t done, put it on another ship to go down the West Coast of Central and South America, get onto a train in northern Chile up into the Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth, to then set up the telescope, reassemble it in the middle of nowhere to take over 10,000 photographs of Mars at a time when Mars and Earth were coming closer together than they had been in years, and where the planet would be better seen from the Southern Hemisphere than the Northern, which was why this was sent to South America.

And so those 10,000 tiny photographs, just one-quarter inch across, were then touted by Lowell and this astronomer David Todd as proof that the canals were there. And the public accepted it. I mean, that’s why in 1907, the Wall Street Journal said we now have proof of life on Mars. And by 1908, you had pastors in church sermonizing about the Martians and saying how we should look to Mars as an example of what we should be because the Martians were thought to be more peaceful and more moral than we are. And by 1909, there was talk of communicating with Mars, as there had been on and off over the years, and people were imagining what we could learn from those intelligent moral beings across the void.

So Lowell, you know, he was investing his money. He was pushing people to actually do this research. And again, I think that’s all for the good. In the end, he was wrong, but that’s how science works.

You include some of those photos in the book, and I have to say, I can put myself in the place of somebody who was just a member of the public. If you looked at those photos and said, well, he probably knows what he’s talking about, you could, I’m sure, convince yourself he was right.

Well, they were tiny grainy photographs. Even the originals, which I have seen, are hard to make out. In retrospect, if looking at Mars through a telescope can cause people to see lines, certainly the same thing can happen looking at a quarter-inch grainy photograph. Your mind can go all sorts of ways about imagining shapes that might be in there. But Lowell had these published in some of the most renowned publications of the time as proof, and the tiny photographs he then accompanied with his own drawings showing what’s “really there.” You had to trust that his drawings that showed the canals beyond any doubt actually matched the photographs. You had to trust that he was doing that right.

Thinking about “Outsider Scientists”

Now, as you alluded to earlier, Lowell is not the only character in this book. There are many interesting figures who come in and out, including Nikola Tesla. In your last book, American Eclipse, you also talked a lot about Thomas Edison. Something I wanted to pull on with you was this idea that there seemed to be—at least at that point, and maybe throughout the history of technology—some of these “men of action” who made astounding technical breakthroughs, but who were somewhat out-of-step with the academic science of their time. I guess Lowell is even more of an edge case, probably even further from the academic mainstream of the time than Tesla or Edison. Do you see “outsider scientists” as a theme of your books?

Interesting question. Tesla and Edison, of course, were very different kinds of people. They would say they were outside the mainstream in different ways. My book American Eclipse tells the true story of a total solar eclipse that crossed America’s Wild West in 1878 and was kind of a defining moment for American science in terms of inspiring us to become a scientific power. There were many interesting people who went West for the eclipse, including Thomas Edison.

At that time, Edison saw himself as not just an inventor, but as a scientist, and he was friendly with a bunch of academic scientists with whom he went to Wyoming and then later, not too much later, had a falling out because Edison was a showman. He was a salesman. He was trying to raise money, trying to put out practical inventions that would sell, and that at times put him at odds with the academic scientists, who were very careful not to sensationalize and not to get ahead of the science, whereas Edison was very happy to tout his inventions even before he’d invented them so he could raise the money to actually invent them.

Tesla was different. You know, Tesla and Edison famously are seen as rivals. Early on, Tesla worked for Edison for a brief time. They had a falling out. I think too much is made of their rivalry, but they did famously engage in the war of the currents, where Edison was promoting direct current electricity. It was Tesla who was promoting alternating current as more practical. And Tesla won. Tesla was right.

Tesla himself was an outsider in a different way. He was a visionary, which back then was used as a pejorative: “visionary,” in that he saw things that weren’t real. That’s good and bad. He imagined things that helped him with his inventions. But he was not a practical man. He was not good with money, and he would dream up these ideas that he would work on forever before bringing anything practical to market. And he had investors who needed to get their money back. They gave up on him because he just he was too visionary and not practical enough.

Edison was very practical. He knew to focus on inventions that could actually make money, not just something that would save the world, whereas Tesla was out to completely revolutionize things and save the world. But he couldn’t do it without the backing of millionaire investors.

So anyway, it is interesting. I hadn’t thought about that. Lowell too, of course, was an outsider. So I guess I am writing a lot about people who are a little outside the mainstream of science.

Influence of Canals on Culture

Another part of The Martians that was really intriguing to me was the way it sort of pulls back some of the layers on our shared cultural imagination around Mars and Martians. When I was in middle school, I enjoyed both The War of the Worlds and The Martian Chronicles, and I think to me they were both sort of equally fictional. They had nothing to do with reality. What I didn’t really grapple with, certainly at that time, was that War of the Worlds was more of an attempt to really think through scientifically, what would a Martian look like? Whereas The Martian Chronicles is more of a fantasy about our human imagination of the stars. In The Martians, you present a lot of original sources of these cultural tropes, which I found really interesting. Did you have any favorites among those?

Oh, quite a few, yeah. When I was growing up in the 1960s and watching Marvin the Martian in Bugs Bunny cartoons, there was also a very popular sitcom called My Favorite Martian starring Ray Walston, who played this Martian who came and crash-landed his flying saucer in California, and he was pretending to be a human. He was kind of hiding out, but he had these antennae that would rise up from his head every once in a while. They were like television antennae.

Sometimes you will see aliens depicted with antennae or Martians with antennae. And I long wondered where that came from. That was one of the fun discoveries I made in the book. Back in the 1890s and the beginning of the twentieth century, there were all sorts of depictions of what Martians might look like. And I can talk more about that in a minute. But the antennae came along actually when a friend of Percival Lowell’s named Edward Sylvester Morse, who was a prominent zoologist and who got wrapped up in the whole Mars craze himself, went to Flagstaff to look through Lowell’s telescope and saw the canals on Mars. And being a zoologist, he thought, well, what would a being on Mars look like? After all, Mars, they knew even then, was extremely dry, had a thin atmosphere, was probably cold. Well, what kinds of creatures on Earth can live in those sorts of environments and might, over the eons, evolve to actually live in an even drier place with an even thinner atmosphere?

Morse realized that no matter where you go on Earth, even the highest mountain tops or the driest deserts, you find ants. And so he thought, well, maybe the Martians are ant-like. And after he made that comment, you start seeing these antennae sprouting from the heads of the aliens as depicted. So that’s where the whole antenna thing came from.

But even today, you know what is the stereotypical depiction of a Martian? Not a Martian, but an alien just generally today? Well, often it’s a skinny creature with a big bald head and giant eyes. That’s very much what the Martians were depicted like, because—well, why? Well, Mars is farther from the Sun than the Earth is, so daylight must be dim. Well, the Martians must have big eyes to capture more sunlight. Why are they tall and skinny? Well, on Mars there’s less force of gravity, so a creature could grow taller without all that weight pulling down on its bones and muscles. So that would allow it to grow taller. Some Martians often had kind of big chests. Well, because the air is thin on Mars, they need big lungs.

But then there was this idea—and this also gets back to H.G. Wells in The War of the Worlds—that the Martians are essentially what humans will become in the future, because Mars was thought to be an older planet than Earth, where intelligence and civilization emerged before they did on Earth, and then kept going. So, well, what will we become in the future? Well, if Darwin was right that we evolved from small headed hairy apes and now we have bigger heads and less hair, well, the Martians farther down that path will have really big heads and no hair. So they’re bald with big heads.

There were a lot of these interesting things about the depictions of Martians. That was a lot of fun.

Reflections on Mars and the Future

I know your time is short now, but I wanted to end with another thing. I’ve seen a lot of science journalism recently that seems a little bit “Mars skeptical”—people who say we’ll probably never go there, that it’s probably hellish, that it’s not a place for humans anyway. But at least in the early pages of the book, you don’t seem to frame it that way yourself. You give the dedication to your book as, “To my nieces and nephews. May your generation be the first to cross the ocean of interplanetary space.” I want to give you a chance in closing to say anything you’d like to say about that, and maybe to comment on what you think Mars means for humans as a concern in the future.

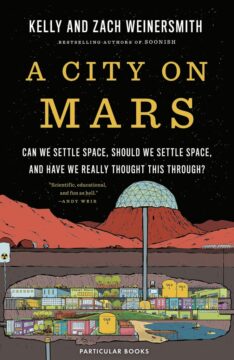

Well, so you mentioned recent books. There was a wonderful recent book called A City on Mars, which is highly skeptical about ideas of colonizing Mars, but also points out that if we’re going to go anywhere, Mars is the place. I mean, the Moon and Mars are the only logical places to start setting up shop for long-term human habitation. Mars is the place, but it’s going to be really, really, really difficult to figure out how to live there long-term.

You know, Elon Musk is obviously a highly, highly controversial character, but I’m thrilled by his promotion of the idea of going to Mars. I should say, I think his idea of colonizing Mars and setting up a city of a million people anytime soon is crazy. Mars is a place that will want to kill anyone who goes there. The atmosphere is so thin that not only do you need to bring your own oxygen with you, but you need to wear a pressurized suit. And there are global dust storms that blanket the whole planet, and the soil is toxic, and there’s radiation constantly bathing the surface of the planet. It’s a dreadful place.

On the other hand, I think Elon Musk is absolutely right that in the long term, if human beings are going to survive, we have to branch out from just Earth. And by that I don’t mean that we should give up on Earth by any means, or that we have to accept that climate change or nuclear war is going to destroy our planet. I’m not saying that. But if we’re going to survive for another couple billion years, which is a really long time, something’s going to happen. An asteroid’s going to strike the Earth. I mean, something awful will happen. So I’m talking really long term. Eventually, human beings, if we’re going to survive, will need to branch out. And Mars is the logical next place.

If you accept that as true, somebody sometime is going to have to start that transition to being multi-planetary. So why not start now? And by starting, I mean, I hope we will see a few astronauts on Mars in my lifetime. I think it’s going to be centuries before there’s a colony there and millennia before there’s any idea of terraforming Mars into something more Earth-like. But I’m excited by the prospect.

My book is both an inspiring tale, because 100 years ago this Mars craze really did launch science fiction and launch our excitement about outer space, but it’s also a cautionary tale about how we can fool ourselves into believing things that aren’t true because we so wish they were true. People were looking at Mars as a better world that we wished existed and they believed existed.

Some of that is going on today. I think when Elon Musk talks about Mars, he’s talking about creating a better world there. It’s going to be a more egalitarian kind of a techno-utopia that will leave behind the problems of Earth. I think that is kidding ourselves, that somehow we can go to Mars and leave humanity’s problems behind, as opposed to bringing our problems to Mars.

So we have to be cautious about thinking that Mars is this blank slate that we just draw on whatever we want to be there. If we’re going to get to Mars, we have to be level-headed about it. But I’m all for giving it a go and hope that we’ll get there before too long.

Thank you, David, for your time. I really recommend this book. It’s a very good read, and even if you think you know the story, there’s a lot of extra interest in there. So thank you again.

I had a lot of fun. Thank you, David.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.