by Eric Feigenbaum

From a corner room in Singapore’s Peninsula hotel, I spent many nights staring out the windows, watch sparks fly silently from the nearby construction sites. Up on the 18th or 14th or 20th floors, Singapore looked still and calm at midnight or 1am. Unlike many big metropolitans, Singapore streets – even in the city center – become quiet at night, especially a weeknight. There was an other-worldly quality watching Singapore’s downtown sleep at night.

My very first visit to Singapore was in February 2004. As business had it, by the end of the year, I was going frequently and for increasingly long stretches – sometimes for seven to ten days at a time, until I rented a condo in March 2025.

But 2004 was filled with nights looking out at the big, fast-moving clouds, giant sky, ships anchored offshore and ever-growing skyline. And sparks. Always sparks coming from below.

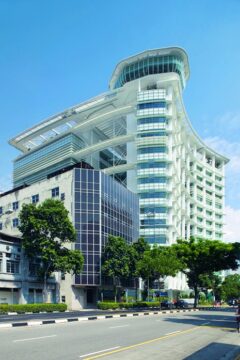

It took me a visit or two to realize the new National Library building being built just a couple of blocks away was under construction seemingly 24 hours a day. Which meant from visit to visit – even if it was just a few weeks between – the building grew rapidly. In fact, the 16-story, 338 foot tall, 121,675 square foot site with a gross floor area of 632,918 square feet was completed in less than 18 months. An amazing accomplishment.

As a comparison point, a recently very similar sized project in San Francisco – the 5M Office Tower at 415 Natoma Street took began in mid-2019, taking two years and nine months. Its cost – $158 million – is only $3 million more than the National Library’s – and ironically, the building received a development loan of $393 million from Singapore’s United Overseas Bank.

In a similar time-period as the construction of the Singapore National Library, my alma mater, the University of Washington, built a new Business School building – PACCAR Hall – on nice flat land in exactly two years from 2008 to 2010. Despite it being five stories and 133,000 square feet of total floor area – almost one fifth of the National Library’s – it still took six months longer to construct.

Obviously, 24-hour a day construction gives Singapore an advantage in construction time. But doesn’t that create around-the-clock noise that disturbs the city? Isn’t it inordinately expensive? Aren’t labor unions protesting?

Singapore is nothing if not a well-regulated society. At all times, Singapore has maximum levels of noise for construction sites. From 7am to 7pm that’s typically no more than 75 dBA of continuous noise over a five-minute period – although certain types of construction (such as the category for the National Library) get 12 hours of continuous noise. From 7pm to 10pm, in most categories of construction, less noise is allowed. And from 10pm to 7pm 50-65 dBA becomes the norm – expect for certain large, non-residential buildings which 65 dBA per continuous 12 hours or 70 dBA per continuous five minutes.

In other words, if contractors can figure out how to manage their noise levels, they can build around-the-clock – which certainly explains the quiet sparks that flew just below the dreaming population of the Peninsula Hotel.

Singapore’s speed is also its thrift because project costs often increase with time. Singapore’s precise use of foreign labor allows it to build faster and more cost effectively than the United States and many other developed nations.

As mentioned previously, Singapore has special work passes for many blue collar jobs and in particular brings in construction workers from Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burma, Cambodia, China, India, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Sri Lanka and Thailand. It has a special higher paid category of permit for workers from “North Asia” – specifically, Hong Kong, Macau, South Korea and Taiwan. These are typically more skilled workers with experience on projects of similar construction standards to those in Singapore.

Workers are paid monthly flat-rate salaries and shifts are allowed to be as long as 12 hours per day and typically work six days a week. Employers must provide housing – usually in a dormitory for workers – and basic health insurance. Construction workers on work passes are forbidden from marrying or getting pregnant a Singaporean citizen or permanent resident. They are paid between S$250 and S$900 ($193 to $695 USD) per month.

With such affordable non-unionized labor and long-shift allowances, it’s easy to see how around-the-clock, rapid construction is possible.

That’s not to say Singapore’s strict segregation of temporary foreign workers and their very low wages isn’t a source of international criticism. At the same time, Singapore is very eyes-wide-open when it comes to the need for foreign labor and is candid and upfront with foreign workers as to what their opportunities are and are not. Construction workers who come to Singapore on work passes know they will not achieve long-term immigration. It’s strictly a chance to earn money in a situation with minimal overhead and send it home or save up.

Accordingly, Singaporeans are generally comfortable with the immigrant workforce because they know it does not displace Singaporean jobs or present a burden on the state – it’s a carefully planned resource that augments their small population.

Contractors have had to go beyond cheap labor to maintain their edge. To meet the sound requirements, reduce costs and increase speed further, Singaporean construction firms have begun using new technologies including robotics.

All these ingredients combined – technology, efficiency, cheap labor – make it so infrastructure projects take a fraction of the time and costs as in the United States.

Here are a couple of examples.

The first phase of the Second Avenue Subway line in New York took from 2007 to 2017 to build and was $800 million overbudget and runs 1.5 miles. From 2002 to 2012, Singapore built its Circle Line MRT – 22.1. miles opened in several phases, the first at seven years with three more segment openings over the course of the next two-and-a-half years. Singapore spent the USD equivalent of $7.7 billion in total – for a per-mile cost of $348,416,290 New York’s train cost $2.5 billion per mile.

Singapore did even better with its Northeast Line – 17 stations running 21.6 miles that took 5.5 years to build at a cost of $3.5 billion USD – or $162,037,037 per mile.

The California High Speed Rail (CAHSR) Project was approved by voters in 2008 and has thus far spent $14.4 billion, completing only minor sections of track and viaduct. The state’s original estimate was $28 billion to $38.5 billion but has since been revised to $89 billion to $128 billion to complete only the Phase One portion of the project by 2038.

Naturally, not every American project is as disastrous at the CAHSR and not every Singaporean project is as efficient at the Northeast Line. But on average, Singapore has figured out how to make construction cost-effective and speedy.

The average new private Singaporean condo block is typically 36 stories tall. Construction takes an average of 18 to 30 months and on average yields between 300 to 600 housing units depending on the size of the land parcel. That means one new private Singaporean condo block produces more family housing that all but one current US new-build construction project and in many cases is completed faster.

But this reveals an even more important outcome. In Singapore, 90.8% percent of people own their home – 80 percent in publicly-built condo blocks. Most of new private construction is for people looking to move from modest to more luxurious housing. Singapore does not face a real housing shortage. In the United States, 65.8 percent of people own their homes and depending on whose estimate you believe, America is short 4.7 to 6.8 million housing units.

Founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew explained why the construction and affordable sale of housing was so critical to multiple dimensions of Singapore’s success:

My primary preoccupation was to give every citizen a stake in the country and its future. I wanted a home-owning society. I had seen the contrast between the blocks of low-cost rental flats, badly misused and poorly maintained, and those of house-proud owners, and was convinced that if every family owned its home, the country would be more stable… I had seen how voters in capital cities always tended to vote against the government of the day and was determined that our householders should become homeowners, otherwise we would not have political stability. My other important motive was to give all parents whose sons would have to do national service a stake in the Singapore their sons had to defend. If the soldier’s family did not own their home, he would soon conclude he would be fighting to protect the properties of the wealthy. I believed this sense of ownership was vital for our new society which had no deep roots in a common historical experience.

In other words, high-quality, effective and rapid construction isn’t just a nicety or an advantage – it’s a major factor in creating social cohesion itself.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.