by Laurie Sheck

1.

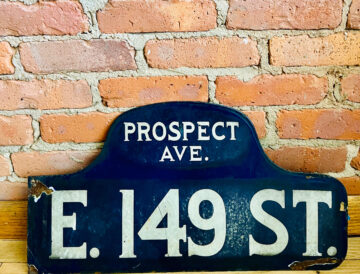

In the summer of 1977 in New York City—summer of the famous city-wide blackout, its fires and looting—my parents stole a street sign. The sign marked the location of my father’s housewares store which overnight had been turned into a hollow shell of blackened ash and charred brick. Looted and burned.

The sign was a remembrance of a place they had loved.

The store was in the South Bronx, which at that time was the highest crime district of NYC. 149 St. and Prospect Ave. From earliest childhood, I spent many hours there dusting shelves, sticking price tags onto merchandise, and performing a variety of other minor tasks. The store and the neighborhood were a large part of my childhood world, of my introduction to what a world even is. My father and his older brother left school in the 9th and 10th grades to support their family. His brother had died young. Now, with the blackout of July 13, overnight the neighborhood was decimated. The store was gone.

2.

Even before the blackout, the South Bronx was notorious for its empty lots and abandoned buildings, its street gangs and drugs. Of course back then, as a child, I was unaware of the statistics. I didn’t know that roughly 20 percent of the buildings stood empty, abandoned by landlords unwilling or unable to maintain them. Unemployment was nearly double the rate of the city as a whole. Fewer than half of heads of households were said to be employed. The median income was $4,600, substantially below the median for the city. One study showed the median household size as 5.0, whereas the median household size for the city overall was 2.2. Families were crowded into tiny spaces. About half of the households were headed by women.

In 1977, the Women’s City Club of New York City issued an extensive report on the area, With Love and Affection: A Study of Building Abandonment. In addition to gathering numerous statistics, the report described the relentless deterioration of the neighborhood dating back to the late 1960’s. The blackout intensified what was already there: “block after block of empty buildings, some open and vandalized, some sealed, standing among rubble-strewn lots on which other buildings have already been demolished. In the midst of this desolation there is an occasional building where people are still trying to live.” It went on, “The streets and sidewalks…are littered with rubbish, with shattered glass out of the gaping doors and windows.” A New York Times article from 1975 bore the headline “To Most Americans, The South Bronx Would be Another Country.”

And yet, even as my memories resonate with much of what the WCC report described, I also remember bustling streets, restaurants, families.

3.

By the time I was two, my parents and I had moved from the Bronx to an apartment in North White Plains, and then, when I was ten, and the family had grown larger, to a house in Ardsley, so my childhood consisted of an ongoing contrast between two very different worlds, as the store continued to be a major part of our lives. This contrast raised many questions: Why did I have things that others did not? Why was my house ok when others’ houses were crumbled down? Issues of inequality and injustice were embedded in my daily life.

In the very earliest years before it was expanded to include the vacated bakery space next door, the store was small with one narrow aisle. The metal shelves were crammed with all sorts of household items. My father had a machine for making keys which, to my child-mind, seemed intensely magical. On the far wall were two white ceramic masks of comedy and tragedy. This made no sense to me. Why were those masks there, what were they doing? And yet they seemed to say something about the world I had entered.- its promises and hauntings. Many clocks hung from the wall behind the cash register, some round, some rectangular, some cat-faced with metronome-tails.

From a very young age I was taught to recognize heroin addicts; my father called them “junkies.” Bloodshot eyes, sallow skin, bony fingers scratching hollow cheeks. The store had a tiny rickety-doored bathroom that scared me. Once, starting to go in, I came upon an emaciated man hunched over and shooting up with a needle in his arm.

One of my jobs was to tell my father if I saw any customers shoplifting. He handled such incidents with what I remember as a gentleness that surprised me. I recall one incident in particular— a matronly woman in a long, flowered dress was trying to carry a toaster out between her knees. Somehow she managed to walk forward. My father approached her very mildly and remarked that it must be hard and uncomfortable to carry it that way, wouldn’t it be better if he could keep it for her on the counter.

Over time, he taught me how to recognize counterfeit bills—the proper texture of the paper, how to look for the embedded red threads, and to count for the proper number of steps on a government building. Not long ago, after my mother died, I found a pile of two dollar bills she had saved, some with handwriting on them in blue pen, clearly from the old neighborhood, “Jaime loves Nesta” and “Papi I love you”; I imagine she meant to check if the serial numbers made any of them worth more than two dollars.

One summer afternoon when I was around five, a very striking, tall, glamorously dressed and made up, beautiful black woman entered the store. “Dad”, I exclaimed, “Look at that beautiful woman,” only to have him reply, “That’s a man.” I stood there and thought, I don’t understand the world; it kept multiplying into vaster and more various worlds than I could ever imagine. Another time, a man dressed as a nun walked through the store taking collection.

When it was raining or bad weather, my father would take in a few homeless people to sit in the back of the store and fold boxes. At night they slept on the roof by the steam vent, warming themselves.

The store sold greeting cards, all sorts of household goods, but also decorative porcelain bulls with golden horns, and paintings on velvet of a crucified Jesus whose electrified blood ran through his veins and dripped from his palms when the picture was plugged in to the wall. These paintings were popular items, as were foot-high ceramic statues of Buddha highlighted with glittering gold.

After the blackout, when I walked into the ruined store, I found one of those Buddhas lying on its side, intact on the charred floor. I took it with me.

4.

There is a prose poem by Charles Baudelaire, Eyes of the Poor, written in Paris in 1855. It is no coincidence that the emergence of the prose poem in France coincided with the rapid urbanization of Paris and the throwing together of a diverse population of varying backgrounds and classes. In Baudelaire’s poem, a man and woman in love have spent the day together. It is evening, they are dining in an elegant café, decorated with “dazzling sheets of mirrors, the gold rods and cornices…” The man, the narrator, notices right in front of them, outside on the sidewalk, a tired man with a graying beard, holding with one hand the hand of a little boy and carrying on his other arm a little child too weak to walk. All three are dressed in rags. As the narrator looks into their eyes, he imagines the little boy’s thoughts as he gazes at the dazzling café: “How beautiful it is! But it’s a house only people who aren’t like us can enter.” The narrator, stirred and troubled by the man and his children, recalls, “Not only was I moved by that family of eyes, but I also felt a little ashamed of our glasses and carafes, which were larger than our thirst. I turned my gaze toward yours, dear love, to read my thoughts there…and then you said to me, “I can’t stand these people over there, with their eyes wide open like carriage gates. Can’t you tell the head waiter to send them away?” At this, a terrible abyss opens between the man and the woman he thought he loved.

What I sensed as a child: Our cities partly show us who we are.

5.

Shortly after the store burned down and we were there for a few days sorting through the damage, people from the neighborhood came by bringing gifts of food, offering condolences, expressing hope the business would return. But for my father and the others he knew—the dress store owner, the guy who ran the laundromat, the owner of the car repair shop, there was really no way to go back. The result was a neighborhood even more abandoned and without services. In 1980, when President Reagan visited the South Bronx, he commented that he “hadn’t seen anything like it since London after the Blitz.” In 1970, the Census Bureau had counted 763,518 people living in the South Bronx; by 1980 the count was 453,925. A 1983 report by the South Bronx Development Organization put the number of abandoned housing units at fifty thousand. Between 1970 and 1981, the Bronx lost one-fifth of its housing stock to abandonment, arson and demolition.

In the 1980’s the city devised a program to cover many of the area’s broken, decimated facades with full-sized decals of attractive doors and windows decorated with brightly colored curtains and flowerpots. An official press release stated, “We do not claim that the ‘Occupied Look’ is the answer to our overall housing problems. However, it does address itself to keeping our city an attractive place to which people want to move.”

When my father and I drove past those facades, it was like looking at weirdly done-up ghosts.

6.

In 1976, the year before the blackout, the artist and architect Gordon Matta-Clark was invited to take part in a prestigious exhibition, “Ideas as Model” curated by Phillip Johnson, at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in Manhattan. The Institute was housed in an elegant brownstone. The other invitees included Peter Eisenmann, Richard Meier and Michael Graves. As Matta-Clark’s widow, Jane Crawford, recalled, “Gordon and I visited the exhibition and watched as the delicate balsa wood and paper models were installed. To Gordon, they represented everything that was wrong with architecture, primarily its exclusivity.” This point of view ran through all of Matta Clark’s work; he spent his working life as an artist (he died at 35) involved with issues of social justice and the landscapes and architectures of urban poverty, disuse, destruction. The night before the opening, ill at ease with the elegance of the exhibition, he and a few friends entered the Institute where, instead of installing the approved project he originally proposed, he hung eight photographs of the South Bronx in the spaces between the windows, and then, with an air gun, shot out the seven large windows of the elegant exhibition space. As Crawford put it, “With that one gesture he had changed the context of the exhibition to that of the South Bronx and those who struggled under the oppression of the rich. In the new context, the exquisite, Avant Gard homes that only the very wealthy could afford were rendered frivolous and irrelevant. When we arrived the next day, the windows had been repaired (an extraordinary feat in such a short time) and the photos neatly wrapped in brown paper and string. Gordon was not welcomed within. I am continually amazed at the resonance of a piece which only a handful of friends actually saw.” The work was titled Window Blow-Out.

7.

When my mother died last year, I moved the street sign into my apartment. Sometimes at night I can almost still feel myself there. Memories come in flashes: the quiet boy standing at the counter, extending his hand to pay but the money he’s holding isn’t enough; Hector who came by for a few days each Christmas to work in the store though he didn’t have to—he wanted to repay my father for footing the bill for his son’s funeral; how the police stopped in to ask that kitchen scales be removed from the shelves because drug dealers used them, and members of the gang, the Savage Skulls, came around to sell my father “insurance”. How day after day I was both frightened and not frightened all at once. How ruin was beautiful and terrible. How in the eyes of a very small child the world was vast, dirty, miraculous, various, unjust.

***