by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

Every civilization eventually reaches the edge of its own understanding. The Enlightenment, which was basically a grand project of faith in reason, sought to replace the mysteries of revelation with the lucidity of thought. It promised that disciplined rationality could illuminate every corner of existence. It was thought that that through observation, experiment, and the methodical accumulation of knowledge, humanity could build a transparent world where nothing remained obscure. Knowledge would rise like light refracted through a cathedral of glass, cleansing superstition and disorder. Yet this grand confidence carried within it the seed of its undoing. The very tools of reason that once liberated humankind also revealed the boundaries of comprehension. The Enlightenment’s most profound legacy was perhaps not infinite clarity but the realization that even reason has horizons it cannot cross. By the twentieth century, the dream of total understanding had hardened into the austere project of formalized mathematics, symbolic logic, and mechanical computation. It finally fell crumbling down. It was a quest to capture truth in the language of machines, and in doing so, to continue the Enlightenment by other means.

Let us begin with Leibniz, who envisioned a future in which every disagreement could be settled through calculation. “Let us compute,” he declared, envisioning a characteristica universalis, a universal language in which thought itself could be reduced to algebraic precision. For him, reason was not merely a human faculty but an architecture of truth. It was a divine syntax underlying the cosmos. Through rational analysis, Leibniz believed, everything from theology to mechanics could be rendered transparent. This was the audacious spirit of the Enlightenment i.e., the conviction that the world, properly translated into the language of reason, would yield its secrets without remainder. Immanuel Kant inherited this dream and showed that reason, while vast, is not infinite, that it generates its own horizon. The limits of reason, Kant wrote, are not defects but conditions of possibility. He thought that we can never know the thing-in-itself (das Ding an sich). This is because knowledge is not a mirror but a creative act, shaping the appearances it seeks to understand. Where Leibniz saw the universe as a divine calculus, Kant saw it as a theater of understanding. The world was ordered by this understanding not by the world as it is, but by the mind that apprehends it. Rousseau afterwards even questioned whether the march of reason brought progress or alienation, warning that civilization’s rational order might enslave rather than liberate.

Enlightenment’s faith endured in science and in the dream that the human mind, through the right method, might still one day comprehend the whole. The early twentieth century began with an almost religious confidence in formal logic. It was believed that formal Mathematics would finally be able to cleanse thought of ambiguity once and for all. Hilbert’s great project was to formalize every branch of mathematics into a consistent, complete system. For all practical purposes, this project carried the old dream of Leibniz into the modern age. If reason could only speak its language perfectly, there would be no remainder, no mystery. In 1931, a shy Austrian logician named Kurt Gödel shattered the dream of Hilbert’ project. His Incompleteness Theorem showed that any sufficiently rich logical system contains true statements that cannot be proven within it. There will always be propositions that are true but unreachable. A few years later, Alan Turing carried Gödel’s insight into the newborn world of computation. His famous halting problem revealed that no machine could decide, in general, whether another machine would ever stop running.

Even in physics, we also encountered the boundaries of knowing. Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle revealed that observation itself is never neutral, the act of measuring alters the very reality it seeks to describe. The clearer our measurements, the deeper our interference. In trying to pin down the position and momentum of a particle, we found that certainty in one meant blindness to the other. Einstein’s relativity also dismantled the dream of fixed truth, showing that space and time themselves were contingent, woven together and dependent on the observer’s frame of reference. And in quantum mechanics, the wave-particle duality forced us to accept contradiction at the heart of reality itself. Richard Feynman, arguably one of the greatest Physicist of the second half of the 20th century put it succinctly, ““I think I can safely say that nobody really understands quantum mechanics,” The Enlightenment dream of total illumination thus faltered not from lack of light, but from the discovery that reality is examined too closely it dissolves into paradox and probability.

By the mid-twentieth century, something had changed. The Enlightenment’s cathedral of reason, once radiant with faith in progress, rationality, and human perfectibility now stood in ruins. The devastation of the Second World War had shattered the idea that reason inevitably led to enlightenment. The same scientific precision that once promised emancipation had also led to the concentration camp and the atomic bomb. The tools of progress act like double edge sword. They are capable of illuminating the world, but they are equally capable of incinerating it. In the ashes of that revelation, confidence in rational mastery gave way to a haunted lucidity i.e., a sense that the instruments of thought and knowledge were themselves complicit in the crisis they sought to explain. From philosophy to literature, this reckoning defined the mood of the age. Wittgenstein turned inward, showing that language itself had limitations i.e., meaning existed not in correspondence with truth but within the limits of its own form. Heidegger traced the disaster to the metaphysics of modernity, arguing that the West’s obsession with mastery had reduced Being to a standing reserve of use. Adorno and Horkheimer, in Dialectic of Enlightenment, gave the diagnosis its most damning form. They stated that the Enlightenment’s triumph over myth had itself become mythic. It was a new form of domination cloaked in the language of progress. In literature, this crisis found its most haunting expression in the voices of Beckett, Kafka, and Camus, whose characters inhabited a universe stripped of order and meaning. It was as if language which was once the vessel of revelation, no longer revealed. After Auschwitz and Hiroshima, the Enlightenment’s dream of total clarity had inverted into its opposite: a recognition that to see too clearly is to glimpse the void. What remained was not silence, but a strange and luminous honesty. It was a poetics of failure that acknowledged, perhaps for the first time, that the limits of knowing are also the conditions of our humanity.

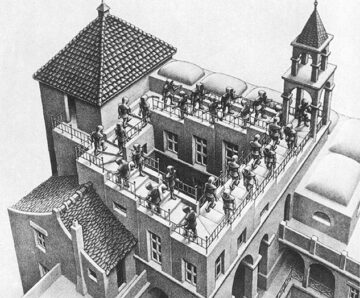

Jorge Luis Borges’ captured the paradox and limitations quite beautifully in The Library of Babel where a library is imagined as an infinite archive containing every possible book, all wisdom and all nonsense intermingled. Each truth is buried beneath an avalanche of nearly identical lies. The librarian becomes a tragic figure, condemned to wander a labyrinth of meaning that exceeds comprehension. When logic reached its boundary, language took over. If reason could not capture the world, perhaps words could trace the outline of its disappearance. The writers and philosophers of the mid-twentieth century discovered that language can often be a labyrinth and not always a bridge to meaning. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus begins with crystalline precision: “The world is all that is the case.” And then, abruptly ends with “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Samuel Beckett inherited that silence and made it speak. In The Unnamable, he distilled the exhaustion of the Western intellect after the collapse of its faith in reason and progress. The novel unfolds as a monologue without beginning or end, a voice that persists long after it has nothing left to say. The narrator’s lament, “I can’t go on, I’ll go on”, is not just existential despair but the purest articulation of consciousness after the Enlightenment’s grand certainties have dissolved.

If the philosophers and poets of the twentieth century wrestled with the limits of language, the twenty-first has tried to outsource them. Our newest mirrors are machines. The Enlightenment’s dream of a universal calculus, the logic that could make thought itself transparent, has returned in the form of code. Large language models digest vast amounts of human expression and speak it back to us, fluent but hollow. We ask them to explain, translate, confess and they answer in perfect empathic tone. Paradoxically, these eloquent machine do not understand what they are describing. The machine, in this sense, is not an oracle but a mirror, one that reflects the limits of comprehension in a new medium. It gives us not knowledge, but an endless recombination of it, a “Library of Babel” with an autocomplete function. When a machine writes a poem, predicts a sentence, or completes an equation, we glimpse the continuation of the same Western impulse that began with Descartes and Leibniz i.e., the belief that thought can be rendered into mechanism. It is also the belief that consciousness can be modeled as a machine. But now the machine writes back, and we are the ones left wondering what, if anything, it means. Perhaps this is the new face of the Western limit: not the boundary of reason itself, but the illusion that reason can ever be boundless. The crisis is no longer ignorance but omniscience i.e., the fantasy that with enough data, computation, and simulation, the world will finally yield its last secret. What once appeared as the humility of inquiry has hardened into the arrogance of total capture, a faith that everything meaningful can be rendered measurable.

At first, the recognition of this limitation may feel like defeat but it is also maturity. To know that we cannot know everything is to discover a new form of reverence, one grounded not necessarily in faith, but in precision. The West’s silence before the unknowable was never the only path. Long before Gödel or Wittgenstein, another civilization had faced the same paradox and responded differently. In the Sufi cosmology of the Islamic world, the limit was not an end but an opening, a threshold through which the finite might glimpse the Infinite. In the next part of this series, The Literature of Limits, Part II: The Islamic Horizon, The Doorway of the Infinite, we turn eastward, to a world where unknowing was not a limitation but a form of devotion, and where the mirror of reason still shimmered with divine light.