by Katalin Balog

In the past, when I asked students if they would want to enter the Experience Machine – a fictional contraption thought up by the philosopher Robert Nozick – they would generally say no. In the Experience Machine, one would have virtual experiences: for example, of a life blessed with mountains of pleasure, great love, monumental achievements. But one would lose touch with one’s actual life. My students did not want to leave their actual lives behind. In the last few years, things have changed. Most of them now proclaim their readiness to ditch it all for the virtual pleasures of the Experience Machine.

My students’ recent eagerness for the virtual is a symptom of our culture’s alienation from the world. During my life, I have witnessed the slow but unstoppable advance of commodification and technology, which has brought us to the threshold of escape from the world – certainly in fantasy, but perhaps in reality, sometime soon.

1 Consuming Experiences

When I was young in my native Budapest, we – my family and friends – didn’t think of life in consumerist terms. We couldn’t, as it was communism, and there was not much to consume – but in any case, the idea of collecting pleasant experiences seemed frivolous and alien. Beautiful Budapest was run down, its buildings still showing bullet holes decades after the war. Tourists didn’t crowd around its “attractions”. It was our city. Sure, we listened to music and attended plays, there were parties where everyone wanted to be, we bought ice cream and cakes, but we didn’t make a habit of maximizing pleasurable, beautiful, or edifying experiences; we didn’t have a plan that would ensure the best results. Much was left to chance and improvisation, as life in those days was hard-scrabble, and things could – and often would – go wrong. Everyday necessities were sometimes hard to obtain, and we had to stand in line a lot. People were generally rude and wielding whatever little power they had in a hostile manner. Our goal was just… to live our life and have the experience that comes with it. But we were also not fazed or annoyed by unexpected obstacles in the way a more committed consumer or tourist would be. Of course, some people I knew went skiing and climbing in remote and beautiful places; that was a thing one could do as well. But most of the time, normal people did normal things, and that was our life. Communism, for a while at least, constrained the consumer in us. I am not idealizing this state of affairs – I was in the underground resisting the oppression that maintained it; just pointing out the difference it made in our attitude to life.

I noticed the contrast between this and what was normal in the West especially clearly when, after moving to New York, I was already between worlds. Read more »

infamous lepidopteran, Cydia pomonella, or codling moth. The pom in its species names comes from the Latin root “pomum,” meaning “fruit,” particularly the apple (which is why they’re called pome fruits), wherein you’ll find this worm. It’s the archetypal worm inside the archetypal apple, the one Eve ate. (Not. The Hebrew word in Genesis, something like peri, just means “fruit.” No apple is mentioned. And please, give the mother of all living a break.)

infamous lepidopteran, Cydia pomonella, or codling moth. The pom in its species names comes from the Latin root “pomum,” meaning “fruit,” particularly the apple (which is why they’re called pome fruits), wherein you’ll find this worm. It’s the archetypal worm inside the archetypal apple, the one Eve ate. (Not. The Hebrew word in Genesis, something like peri, just means “fruit.” No apple is mentioned. And please, give the mother of all living a break.)

The Australian author Richard Flanagan is the 2024 winner of the prestigious Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction for his book Question 7. The book is a brilliant weaving together of memory, history, of fact and fiction, love and death around the theme of interconnectedness of events that constitute his life. Disparate connections between his father’s experience as a prisoner of war, the author H.G. Wells, and the atomic bomb all contributed towards making Flanagan the thinker and writer he is today. The book reveals to us his humanity, his love of family and of his home island of Tasmania; it is what Flanagan expects of a book when he says, ‘the words of a book are never the book, the soul is everything’, and this book has ‘soul’.

The Australian author Richard Flanagan is the 2024 winner of the prestigious Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction for his book Question 7. The book is a brilliant weaving together of memory, history, of fact and fiction, love and death around the theme of interconnectedness of events that constitute his life. Disparate connections between his father’s experience as a prisoner of war, the author H.G. Wells, and the atomic bomb all contributed towards making Flanagan the thinker and writer he is today. The book reveals to us his humanity, his love of family and of his home island of Tasmania; it is what Flanagan expects of a book when he says, ‘the words of a book are never the book, the soul is everything’, and this book has ‘soul’.

After I moved from the UK to the US it took me only a couple of years to cede to my friends’ pleas and start driving on the right. When in Rome, and all that. But I still like to irritate Americans by maintaining that we Brits are better at this essential mechanical skill. I mean, when we drive, we

After I moved from the UK to the US it took me only a couple of years to cede to my friends’ pleas and start driving on the right. When in Rome, and all that. But I still like to irritate Americans by maintaining that we Brits are better at this essential mechanical skill. I mean, when we drive, we  Sughra Raza. Ephemeral Apartment Art. Boston January 4, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Ephemeral Apartment Art. Boston January 4, 2025.

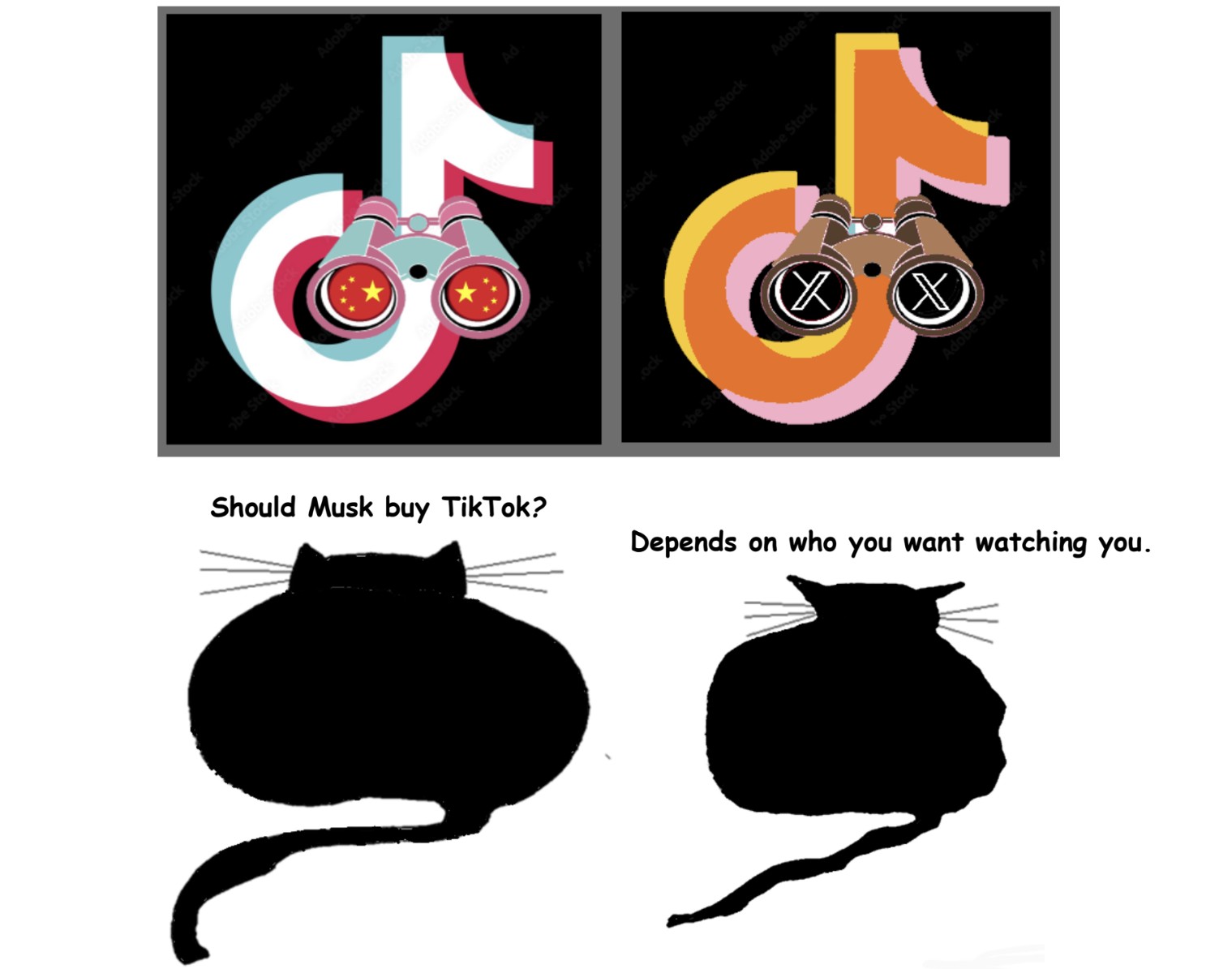

The same media that warned us against Donald Trump now warn us against tuning out. Though our side has lost, we must now ‘remain engaged’ with the minutiae of Mike Johnson’s majority

The same media that warned us against Donald Trump now warn us against tuning out. Though our side has lost, we must now ‘remain engaged’ with the minutiae of Mike Johnson’s majority

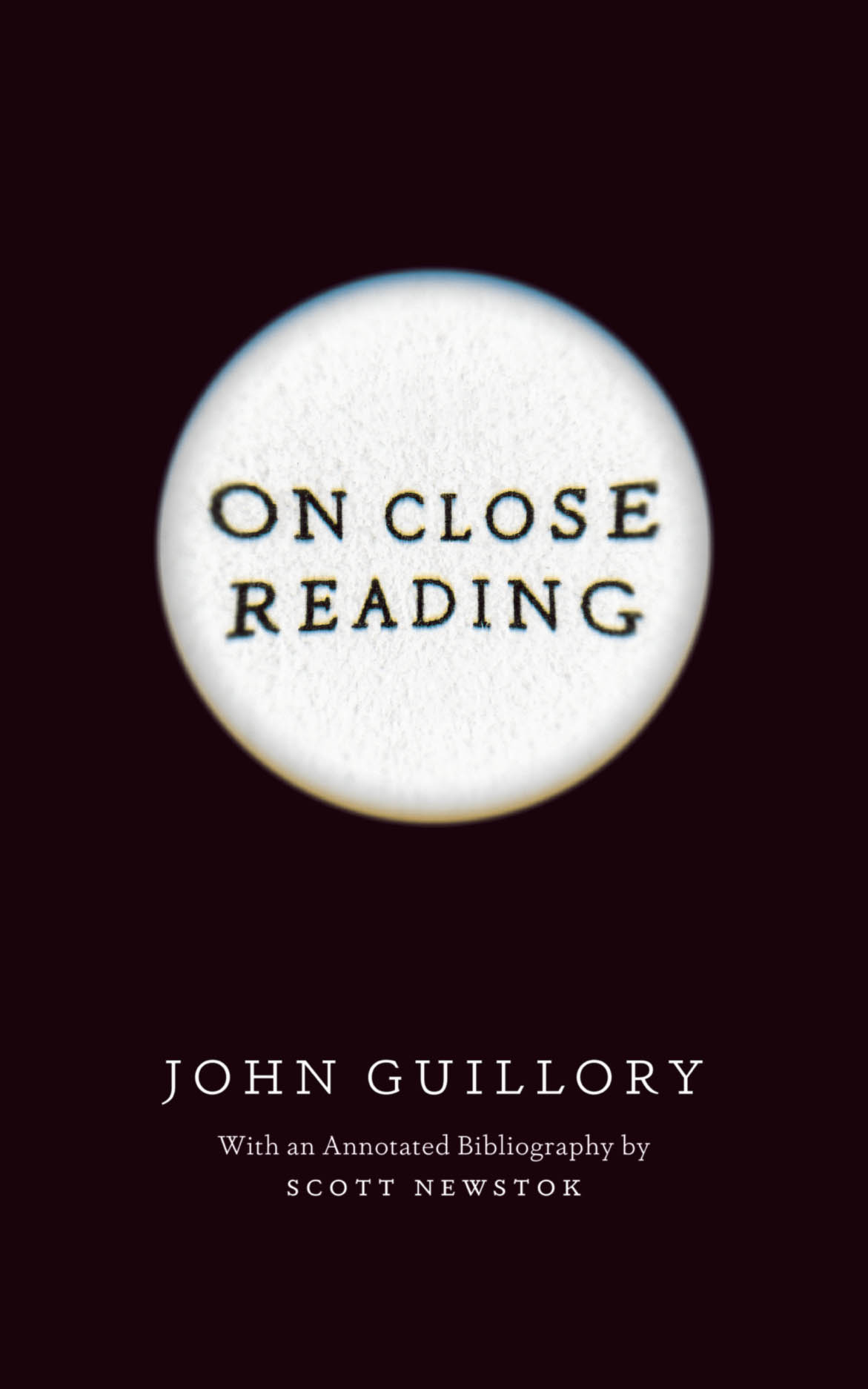

What do swimming, running, bicycling, dancing, pole jumping, tying shoelaces, and reading all have in common? According to John Guillory’s new book On Close Reading, they are all cultural techniques; in other words, skills or arts involving the use of the body that are widespread throughout a society and can be improved through practice. The inclusion of reading (and perhaps, tying shoelaces) may come as a surprise, but it is Guillory’s goal in this slim volume to convince us that reading, and in particular, the practice of “close reading,” is a technique just like the others he mentions. This is his explanation for the questions he explores throughout the book—namely, why the practice of “close reading” has resisted precise definition, and why the term itself was so seldom used by the New Critics, the group of theorists most associated with it.

What do swimming, running, bicycling, dancing, pole jumping, tying shoelaces, and reading all have in common? According to John Guillory’s new book On Close Reading, they are all cultural techniques; in other words, skills or arts involving the use of the body that are widespread throughout a society and can be improved through practice. The inclusion of reading (and perhaps, tying shoelaces) may come as a surprise, but it is Guillory’s goal in this slim volume to convince us that reading, and in particular, the practice of “close reading,” is a technique just like the others he mentions. This is his explanation for the questions he explores throughout the book—namely, why the practice of “close reading” has resisted precise definition, and why the term itself was so seldom used by the New Critics, the group of theorists most associated with it. A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.

A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.