by R. Passov

There’s a small, interesting book store in NYC, small enough for a pixie-of-a-lady and about 200, mostly rare, mostly old, and almost exclusively, cookbooks. The store is near my favorite bar and that’s all I’m going to say.

I first wandered into that shop while trying to walk off a handful of afternoon beers (at that favorite bar). I’ve since gone back many times, usually in search of quirky presents such as a picture book, made in the late 1970’s that contains a replica of every label for every bottle of Italian wine that had been offered in the prior one hundred years – exactly what to get an Italian friend who makes his own pasta and wine. For another close friend I procured a first edition of Diet and Reform by M K Gahndi, perfectly fitting in my view as I had come to believe that close friend was in need of both.

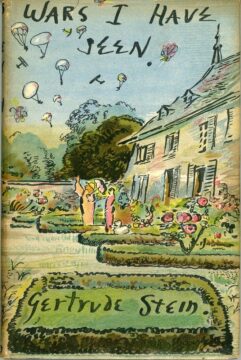

But this essay is not about that bookstore or the nearby bar nor the books in that store that I have found for others. This essay is about a rambling discourse, written as WWII approached its last summer, written mostly in Culoz, France, a small town much closer to Switzerland than to Paris, where Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas spent the last years of WWII.

Stein’s book, Wars I have Seen, is a repetitive reflection on living in the foothills during the waining days of the war. The French were emerging from one regret – that of having lived meekly under the dominion of the Germans – into another. They had allowed for their own subjugation by such a meek foe, as though the shame was not in having been conquered but rather that the conquerors turned out not to be all that.

I knew nothing about Wars I Have Seen. What caught my attention was first its cover – a distinctive jacket design by Cecil Beaton – and next that, unlike almost all other books in that shop, it was not a cookbook. Read more »

If there is one commonly held “truth” that governs conventional wisdom about wine tasting, it is that wine tasting is thoroughly subjective. We all have different preferences, unique wine tasting histories, and different sensory thresholds for detecting aromatic compounds. One person’s scintillating Burgundian Pinot Noir is another person’s thin, weedy plonk. But this “truth” is at best an oversimplification; like a very good Pinot Noir, matters are more complex.

If there is one commonly held “truth” that governs conventional wisdom about wine tasting, it is that wine tasting is thoroughly subjective. We all have different preferences, unique wine tasting histories, and different sensory thresholds for detecting aromatic compounds. One person’s scintillating Burgundian Pinot Noir is another person’s thin, weedy plonk. But this “truth” is at best an oversimplification; like a very good Pinot Noir, matters are more complex.

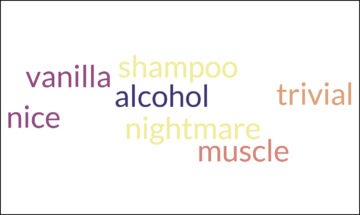

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature?

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature? As a lawyer I know too well that lawyers are infamous for looking for the dark lining in a silver cloud. That outlook goes with the territory of trying to look for legal pitfalls and hidden trap doors. That’s part of the job of what lawyers do—trying to protect their clients from legal liability and unexpected detours and disasters that could have been avoided by careful drafting or strategizing. That doesn’t mean lawyers are pessimists but sometimes it is taken that way.

As a lawyer I know too well that lawyers are infamous for looking for the dark lining in a silver cloud. That outlook goes with the territory of trying to look for legal pitfalls and hidden trap doors. That’s part of the job of what lawyers do—trying to protect their clients from legal liability and unexpected detours and disasters that could have been avoided by careful drafting or strategizing. That doesn’t mean lawyers are pessimists but sometimes it is taken that way.

One day I went to

One day I went to  I gazed at the pages,

I gazed at the pages,

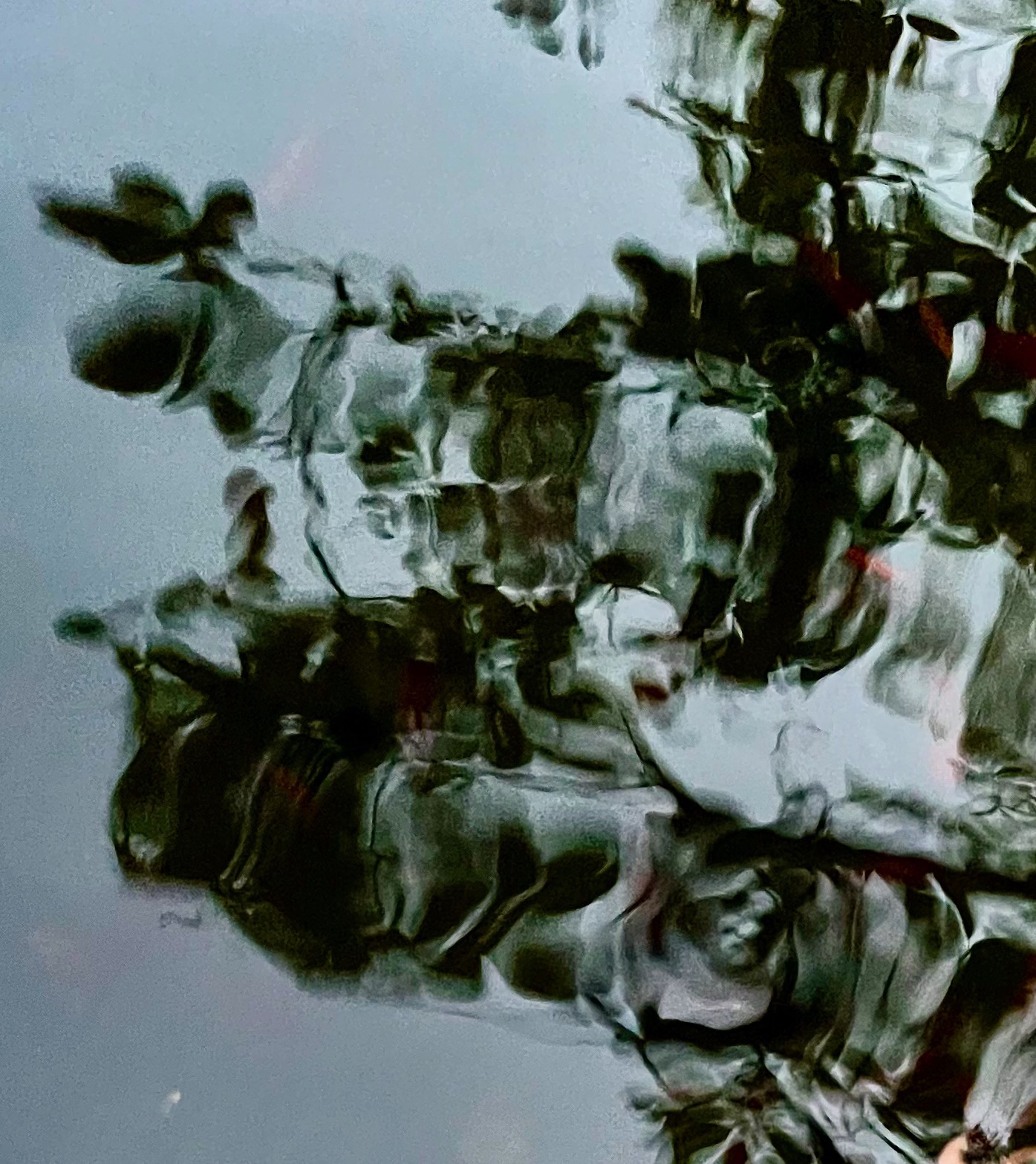

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.