by R. Passov

There’s a small, interesting book store in NYC, small enough for a pixie-of-a-lady and about 200, mostly rare, mostly old, and almost exclusively, cookbooks. The store is near my favorite bar and that’s all I’m going to say.

I first wandered into that shop while trying to walk off a handful of afternoon beers (at that favorite bar). I’ve since gone back many times, usually in search of quirky presents such as a picture book, made in the late 1970’s that contains a replica of every label for every bottle of Italian wine that had been offered in the prior one hundred years – exactly what to get an Italian friend who makes his own pasta and wine. For another close friend I procured a first edition of Diet and Reform by M K Gahndi, perfectly fitting in my view as I had come to believe that close friend was in need of both.

But this essay is not about that bookstore or the nearby bar nor the books in that store that I have found for others. This essay is about a rambling discourse, written as WWII approached its last summer, written mostly in Culoz, France, a small town much closer to Switzerland than to Paris, where Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas spent the last years of WWII.

Stein’s book, Wars I have Seen, is a repetitive reflection on living in the foothills during the waining days of the war. The French were emerging from one regret – that of having lived meekly under the dominion of the Germans – into another. They had allowed for their own subjugation by such a meek foe, as though the shame was not in having been conquered but rather that the conquerors turned out not to be all that.

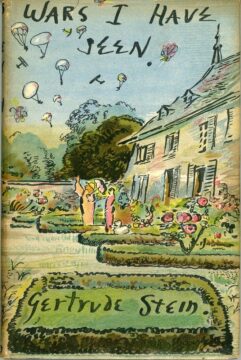

I knew nothing about Wars I Have Seen. What caught my attention was first its cover – a distinctive jacket design by Cecil Beaton – and next that, unlike almost all other books in that shop, it was not a cookbook.

During my first visit to that store, the tiny woman shared her recipe for baked tomatoes in parmesan cheese, and that she had a daughter both living in and doing something important in London and that the financial success of her ‘place’ had given her the means to enjoy a house in the country.

“But you are wondering…” she said and then answered her own question: “My husband and I were both store clerks at Barnes and Noble way back when and we had a small flat with intermittent heat and no health insurance yet somehow we managed to save to the point where we were able to buy the building that houses this shop, way back when no one wanted to by a building on the outskirts of Greenwich Village. And by the way,” she added with a wolf’s grin, “the building runs all the way through to the next block.”

Well, anyway, as Stein might have written were she writing about such an encounter, after our polite and seemingly intimate conversation, I paid more than I should have to take Wars I Have Seen from her small shop to my library. And of course, on my next visit to her shop – I’ve been back several times – we introduced ourselves as though it were my first time in her store.

Past the beautiful book jacket, which depicts in floating watercolor Toklas standing behind Stein who’s covering herself on a sunny day with an umbrella, while both are standing just in front of their magnificent villa in Culoz, ostensibly looking over the garden that so wonderfully sustained them during that terrible war, there is not all that much to recommend.

The writing, conversational as it is, is hard to follow. It wanders much as semi-formal conversations of those times might have, bound with repeated words to the effect that the reader is forced to slow down and re-read, often, with the results being mostly unsatisfactory but every so often so satisfactory as to foster the drive to search for more. Take this for example, from Page 6:

… in a way that’s what makes it nice about France. In one war, they upset the Germans by resisting unalterably steadily and patiently and valiantly for four years, in the next war they upset them just as much by not resisting at all and going under completely in six weeks. Well that is what makes them changeable enough to create styles.”

Or this from page 5:

… a farmer on a hill said of the Germans, do not say that it had to do with their leaders, they are people whose fate it is always to chose a man whom they force to lead them in a direction in which they do not want to go.”

Until very recently, what I had thought separated my country’s history from that of others was our capacity to do just the opposite, to again and again in our times of great need find those leaders that took us through our valleys and into light. Alas.

So it is that in between mundane ramblings on life during a war – which show how during war and great uncertainty people crave, and find, mundane normalcy, find themselves capable of talking about the loss of someone’s son while on the way to the bakery – you will find this on page 9: “… seeing the future is not important anymore. The world has become so shrunken and it will never be different and so does not mean much and there is no love interest it’s mostly parents who suffer…’

Or this, on page 16: “… money is always there, but the pockets change.”

Or this on page 20, which shows such an intimate understanding of the various degrees of defeat: “… being vanquished was a sadness on a sorrow and a weakness and a whoa, but it was not a horror.”

As the book reaches its middle passages, the best parts are when her fine lens shows the beginnings of the separation that precedes defeat: How the Italians were brought into the hills, newly occupied as the boarders of Vichy France receded, and the German Army, exhausted by the Russians, began to suffer closer to home. And how the Italian Army, never wanting to fight, began to atomize, to show themselves to their captives, to show their humanity to the French Villagers, also sensing the change in tide.

Stein describes how Italians in her house

… went in one door and came out another and then they were still there, but otherwise they were sad. They hated the Germans and they liked everybody else … we were sorry for them and they said they hope that they would stay here until the end of the war, and the next day they had to go away and they went around, saying goodbye to the village, where they had only been for eight days as if they were saying goodbye to the village in which they had been born.”

And then, soon after, she catches a sentiment that I see growing in my contemporaries. Speaking of the French: In a little over 100 years, they’ve had three different republics, two kinds of kingdoms, a commune, a dictatorship,

…and this present government of 1943 and yet they worry about what the next government is going to be. I say why worry it can be anything and if it is, it can change … and after all, what difference does it make except to the people in power it certainly does not make any difference to anybody else certainly not.”

And then again, almost 100 pages in, she gets to something also pertinent to our times. She describes how she had enjoyed a permanence that was at once natural and necessary to progress. “If things were permanent,” she writes, “you can believe in progress if things are not permanent progress is not possible … the 19th century believed in progress… And now well … Nobody … is interested in … progress … nobody.”

And finally, I reached the passages that surprised me most. In a book about, among other things, the final death of the 19th century, Stein shows what brought hope and anticipation back into life. Writing on page 102:

I was just listening to an account by one of the American generals of the simple things for which Americans are fighting and the first thing they mentioned is that you can be in your home and nobody can force their way in and authoritatively frighten you … it is extraordinary that the American general should understand that that is why any American could fight … that nowhere in the world should those who have not committed any crime … not live peacefully in their home go peacefully about their business and not be afraid, not have uneasiness in their eyes … I do think it very extraordinary that the American general should have so simply understood that.”

Then more hope, as she writes, on page 165, of coming across scores of American soldiers at the train station and of saying hello to one group and then another,

… I was thinking some of them might have heard of me, but lots of them had and they crowded around and we talked and we talked. It was the first time I’ve been with a real lot of honest to God infantry and they said that they were just that … and they told me about where they had been and what they thought of the people they had seen and then they wanted autographs and … one of them told me they knew about me because they study my poems along with other American poetry in the public schools.”

In the early to mid part of the last century, in American schools, those whose lot would be the infantry during WWII studied the poems and writings of two matronly lesbians who resided, first in Paris and then, in the French countryside.

This surprising encounter with ‘honest to God’ infantry who knew of her works led Stein to discourse on how the American soldier had changed from what she had first seen during the First World War – a soldier that did not converse, where hours passed and they never said a word and seemed to not know who they were nor why they were where they were. And how things had so changed in a mere “…almost 30 years, how this army …talked and listened each one of them had something to say … they converse and what they say is interesting and … one said that he was born on a racetrack and worked in a nightclub another was the golf champion of Mississippi,” and from their public schools they knew the poetry of far away things and places.

And this observation – that the honest to God American infantry man had changed over the course of two wars – led Stein to a discourse on what may have caused the change:

…in the meanwhile, five MPs had come to stay in the station to watch the stuff on the trains and see that it did not get stolen and … we got to be very good friends and they were the first ones with whom I began to talk about the difference between the last army and this army, why is it I said … You don’t drink much I said no we don’t and we save our money they said and we don’t wanna go home and when we get there not have any money we want to … look around and to find out what we really want to do well I explained … I used to complain about American men … that as they grow older, they do not grow more interesting … yes … one of the soldiers [said] … you see the depression made them know that a job is not all there was to it as mostly there was no job … you would see a college man digging on the road … and so we all came to find out you might just as well be interested in anything since anyway your job might not be a good job.”

They went on she said and agreed that the depression had a lot to do with the difference between the two armies. People stayed home; they had no money to go out. But when it came time to train in the army, “…everyone sobered … up … some of them said the radio had a lot to do with it. They got the habit of listening to information and then the quizzes that the radio used to give kind of made them feel that it was no use just being ignorant …”