by David Greer

Countries love their symbols. But what do those symbols tell us?

One of President Biden’s final actions before handing over the keys to the White House was to sign into law a unanimous bipartisan bill, perhaps one of the last of those for a good long time, declaring the bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) the national bird of the United States of America.

Cue media yawn. December 2024 was too replete with Trumpian outrage (for and against) to notice. Besides, hadn’t the eagle as national symbol been settled a couple of hundred years ago?

Actually, more like 250 years ago, when the Continental Congress, having loosed the chains of empire, decided in 1782 to insert the image of a bald eagle on the Great Seal of the United States. On it, the eagle clutches an olive branch in one talon, a sheaf of arrows in the other – prepared for peace or war as circumstances require. The bald eagle must have seemed an obvious pick as a national symbol, the epitome of strength and independence and native to every state in the union. Generations of Americans grew up assuming the bald eagle was their national bird, but that status didn’t become official until the 2024 bill, introduced by Amy Kobuchar, sailed through both the Senate and House and landed on the president’s desk.

Strong, Independent, Often Threatened: The Struggle for Survival of the Bald Eagle in America

National symbols are carefully chosen to represent a country’s identity and values. Unfortunately for the bald eagle, its strength and independence weren’t universally respected in the United States. While the average eagle weighs less than ten pounds, its impressive size with outstretched wings made it an easy target for the long guns of Americans who viewed bald eagles less as magnificent creatures and more as vermin, predators of livestock and plunderers of salmon. Other hunters targeted the eagle as a trophy, especially for its feathers.

This relentless onslaught left its mark. A population of bald eagles that may have exceeded a hundred thousand in the contiguous United States in the eighteenth century was reduced to mere hundreds in the twentieth, and to zero in some states.

Determined to halt the steady decline, in 1940 Congress enacted the Bald Eagle Protection Act, which made it a crime to kill or disturb a bald eagle and to possess eagle parts (including feathers and eggs) and nests. So far so good – until that initiative got blindsided by the agriculture industry’s demand for DDT, a synthetic insecticide developed later in the 1940s. The law of unintended consequences wasted no time kicking in as DDT leached into watercourses, there to accumulate in increasing concentrations first in plankton, then in small fish feeding on them, and finally in salmon and other larger species that were a staple of the bald eagle’s diet. Ingestion of the poison by female eagles altered their calcium metabolism, resulting in thinner eggshells unable to support the weight of an incubating adult. Eagle eggs began cracking in the nest.

The only positive thing about eagle egg omelets was the role they played in awakening a global environmental movement. By revealing the connection between agricultural use of DDT and the decline in eagle populations, Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring sparked national outrage that culminated, a decade later, in prohibition of most uses of the chemical and ultimately led to a groundswell of support for an Endangered Species Act, which became law in the United States in 1973. By 2007, the eagle population had recovered sufficiently for the bird to be de-listed as a threatened species.

The Bald Eagle Protection Act (now the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act) prohibits the shooting of eagles. Instead, eagle populations are now under threat from the ingestion of spent ammunition lodged in animal carcasses and, to a lesser extent, lead fishing weights. The American Eagle Foundation reports that a lead fragment the size of a grain of rice can be lethal to an adult eagle and that a standard 150 grain lead bullet may contain enough lead to poison ten eagles. A 2022 study found that nearly half of over a thousand eagles tested across 38 states exhibited signs of acute lead poisoning.

Fortunately, bald eagle populations continue to be stable for the time being. Life for endangered species in the United States promises to become a little more challenging in 2025, given the second Trump administration’s determination to disable regulations perceived to hamper industry. On March 12, the restructured Environmental Protection Agency announced plans to roll back almost every existing rule designed to protect clean air and water. President Trump has also announced his intention to assemble a “God squad” to veto Endangered Species Act protections for species on the brink of extinction.

The Canada Jay – Raucous Trickster of the North Woods

Canada has a national bird too. The Canada jay, native to every Canadian province and territory, has been recognized as my country’s national bird since 2016, following a countrywide poll by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. When I hear the distinctive call of the Canada jay (Perisoreus canadensis) in the Canadian woods, I’ll sometimes hold out a handful of trail mix at arm’s length. It’s usually only a minute or two before a jay alights on my palm to grab a peanut or two. Blue jays and Steller’s jays would never be so bold, though a chickadee might be tempted.

Canada jays are remarkably trusting, but fearlessly aggressive when the occasion demands. A two-ounce jay raucously chasing a 10-pound bald eagle from its territory is a sight marvellous to behold. Sassy and smart, the Canada jay doesn’t fly south for the winter but flourishes in subzero forests.

Also known as the gray jay or whiskeyjack (an Anglicized version of the Cree word wisakedjak, meaning trickster), the Canada jay is a corvid (like the raven, crow, and other jays) and, as such, one of the smartest birds in the world. Bald eagles are by no means at the bottom of the class, but they are mentally clumsy compared to the agility of jays (social birds like jays tend be smarter than rugged individuals like the eagle).

Canada Extends a Helping Hand – Restoring U.S. Eagle and Buffalo Populations

The resurgence of bald eagle populations in the lower 48 states since their low point in the 1960s was due in no small part to support from Canadian biologists and provincial governments. In Massachusetts, where the number of nesting pairs had fallen to zero, the state Fish and Wildlife agency in the 1980s contacted a Canadian wildlife biologist who then coordinated a program to remove eaglet fledglings from their nests in trees on Cape Breton Island and transfer them to Massachusetts. These 36 eaglets grew up and did what comes naturally, and in due course the state population rebounded to more than 500. Farther west, Manitoba provided eaglets to rebuild populations in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

More recently, indigenous nations in Canada teamed up with tribes across the border to transport bison (commonly known as buffalo) from a Canadian national park to Montana to seed a wild herd where none had existed for well over a century. The buffalo, officially designated the national mammal of the United States in 2016, had come perilously close to being ineligible for such a distinction by virtue of being extinct, thanks to the grim and determined efforts of legions of nineteenth century riflemen to rid the Great Plains of the tens of millions of buffalo that roamed their grasslands home where the skies are not cloudy all day, generally minding their own business and providing sustenance for the indigenous peoples who thought of buffalo as their equals, as people like themselves, and still do today.

One army colonel reported observing a herd that was 50 miles wide and took five days to pass a given point, such was the enormity of the gatherings of buffalo. To give the riflemen credit for persistence if for no other reason, they came damnably close to achieving their objective, thanks to buffalo being a very large target even for the most nearsighted of hunters and to the encouragement of a federal U.S. government that shrewdly concluded that eliminating the buffalo would coincidentally also eliminate the primary food source of tribal peoples and force them in desperation to agree to be confined to reservations, thus freeing up billions of acres for white settlement. Another army colonel, in the 1860s, was heard to tell a wealthy hunter, “Kill every buffalo you can. Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” By the end of the century, the tens of millions had been reduced to fewer than a thousand, mostly scattered in tiny herds of fewer than 20 animals.

Every so often, a national leader comes along who is not cut from conventional political cloth and places the interests of the nation ahead the narrow interests of himself (less frequently herself) and his cronies. Such a leader was Theodore Roosevelt, president of the United States from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt was a swimmer against the tide insofar as he felt unsettled by the conversion everywhere of wild lands for ranching and cultivation and advocated for the conservation of large tracts of land for conservation of natural capital and for public enjoyment. During his decade in office, the roughly 230 million acres of public lands that he established included 150 national forests, 55 bird reservation and game preserves, five national parks and the first 18 national monuments.

Roosevelt observed in 1907 that “the conservation of natural resources is the fundamental problem. Unless we solve that problem, it will avail us little to solve all others.” He was also troubled by the extinction or near extinction of once abundant species. He may have been thinking either of the passenger pigeon (another victim of the American rifle, reduced from an estimated three billion birds to a single captive bird that expired in 1914, once and for all bringing to an end millions of years of evolutionary development) or of the American buffalo when he remarked, “When I hear of the destruction of a species, I feel just as if all the works of a great writer had perished.” It’s an eloquent thought, in part because the analogy is so apt in evolutionary terms.

Some bright light in the Canadian administration, a contemporary of Roosevelt, apparently held similar views. In 1907, with wild buffalo clearly on the path to extinction, representatives of the Canadian government made arrangements to purchase the largest remaining wild buffalo herd in the United States, the Pablo-Allard herd. This turned out to be an inspired decision that later made possible the continuation of wild buffalo herds.

Of the 628 wild buffalo in the Pablo-Allard herd, 398 were transported to Edmonton’s Elk Island National Park, to graze in peace and procreate, which they continued to do for slightly more than a century until 2014, when seven indigenous tribes and nations came together to sign the Buffalo Treaty, under which they would cooperate to restore buffalo herds across their traditional range in the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains. Domesticated buffalo could not be used to restore wild herds, and genetically pure buffalo herds from Yellowstone National Park were considered suspect due to their potential exposure to a cattle disease, brucellosis.

The Elk Island population in Alberta provided an option for genetically pure, disease-free animals to seed wild herds. The objectives of the Buffalo Treaty came to fruition in 2016 with the relocation of a number of buffalo from Elk Island to the Blackfoot reservation in Montana, to form the nucleus of a herd that would freely roam a landscape of over 4,000 square miles.

The return of wild buffalo is good news for native prairie grasslands, which flourish with the soil disturbance and fertilizer that accompanies the presence of buffalo, supporting the return of a range of other species associated with native grassland ecosystems. Eight years later, in 2024, more than 40 indigenous tribes and nations gathered to renew the Buffalo Treaty, an event commemorated in the documentary Singing Back the Buffalo.

Canada’s national mammal, the North American beaver (Castor canadensis), was also driven close to extinction thanks to a European fashion craze – the beaver hat, including what became known as the top hat. Beavers are not only the most industrious of creatures, they enrich landscapes and ecosystems by felling trees and building dams of branches and mud that create or enlarge natural ponds and wetlands.

Both the buffalo and the beaver have been honoured on their countries’ coins. The buffalo appeared on the American nickel from 1913 to 1938 and, since 2006, on the 24-karat “gold buffalo”. The beaver has graced the tail of the Canadian nickel from 1937 to the present day and will undoubtedly outlive the coin itself.

Yesterday’s Ally, Tomorrow’s Enemy – The American Eagle Goads the Canada Jay

Part of the strategy of making America great again apparently involves reaching back into the mid-nineteenth century to revive Manifest Destiny, the weird rationale for America’s assumed God-given right to swallow up neighbouring territories. Manifest Destiny wasn’t mentioned during the Trump campaign for the presidency, so eyebrows were raised when he first spoke dreamily of Canada being the 51st state. It soon became clear that such idle musing wasn’t just a joke, and that the saner voices that restrained President Trump in his first term were no longer present in his second.

Why annex Canada? Well, for national security reasons, apparently. Also because the United States has been so horribly treated by everyone, everywhere, since time immemorial, and maybe earlier than that. And because the border doesn’t look very straight. Stuff like that.

Mr. Trump may not like Teddy Roosevelt’s views on conservation, but he seems to have an affinity for Roosevelt’s advice to leaders: “Speak softly, and carry a big stick.” Especially the big stick part.

The big stick of choice, for the time being, seems to be the threat of ever-increasing tariffs, including destroying Canada’s automobile industry, should that country have the temerity to retaliate. If that doesn’t soften up the Canadians, well, it seems there might be other ways.

A word of warning, though. Past invasions of Canada by the United States have not gone well.

Canadians might be forgiven for feeling gobsmacked at the rapidity with which a long-time ally has so viciously turned on them after all they have done for their American friends in the past, fighting alongside them in multiple wars (WW I and II, Korea, Afghanistan, and others), providing American airline passengers safe haven in Newfoundland during the 9/11 attacks, and remaining a steadfast economic partner that has consistently honored trade agreements, unlike someone we won’t mention here. As described above, Canadians also have a history of always being ready to lend a helping hand in smaller ways, such as making it possible to reverse the near extinction of the United States’ national mammal and bird.

Speaking of which, it’s worth noting that the farther north the habitat, the bigger the eagle, which means Canadian eagles tend to be larger and stronger than their counterparts in the lower 48 states (though not Alaska). Is that the image a president wants to promote when musing about his northern neighbor being weak and ripe for annexation? Possibly not.

Then there’s the fact that female bald eagles are typically 25% larger than males. That seems an awkward national symbol for an administration that likes to glorify hypermasculinity and goes out of its way to fire strong women in the highest positions in government.

For an administration that prides itself on overturning institutions on a whim, maybe it’s time for an executive order replacing the bald eagle as the American national bird. There’s no shortage of choices that haven’t been taken by other countries and better reflect the character of the current administration. The mockingbird? The cuckoo, which makes a habit of raiding other birds’ nests and breaking their eggs?

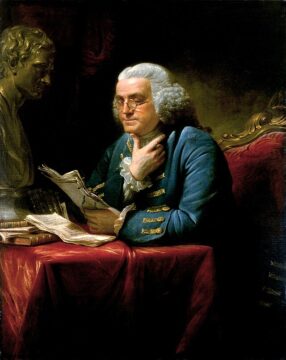

On the other hand, maybe the bald eagle is not such a bad choice after all, given the Trump administration’s fondness for bullying. Two years after the Continental Congress settled on the bald eagle for the Great Seal of the United States, Benjamin Franklin lamented the choice, pointing to the eagle’s preference for scavenging and for stealing from other birds such as ospreys rather than catching its own prey. “For my own part,” he wrote, “I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral Character. He does not get his Living honestly. … Besides, he is a rank Coward: The little King Bird not bigger than a Sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the District.”

Quite so. And just like the little kinglet, Canada jays across the length and breadth of their country appear to be uniting in their determination to drive the marauding eagle back to his lair.

As British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli said, “Courage is fire, and bullying smoke.” A great deal of smoke has been emanating from the White House in recent weeks, and the fire is building in Canadian hearts.

* * *

Thanks to Myles Clarke for generously permitting use of his eagle and buffalo images in this article.