by Rafaël Newman

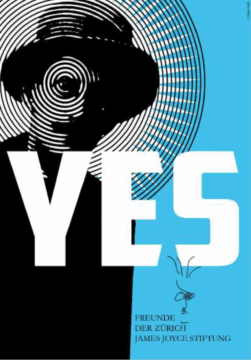

Zurich was James Joyce’s home on several occasions. The writer’s first sojourn there, in 1904, was brief: when the prospect of a job teaching English in Switzerland didn’t pan out, he and his partner, Nora Barnacle, freshly arrived from Dublin, soon moved on to Trieste, then still the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s only seaport. Joyce and Nora returned to Zurich in 1915 and spent most of the Great War there, renting apartments in various districts as Joyce worked on Ulysses and took part in the intellectual life of a city teeming with refugees. Finally, having spent the interwar period for the most part in Paris, by 1940 the couple were back in Zurich, where Joyce died the following year. He remains in the city to this day, in Fluntern Cemetery, where his seated memorial gazes out wryly, if myopically, at Lake Zurich and the Alps beyond.

That the Swiss metropolis boasts the Zürich James Joyce Foundation, however, an internationally renowned center for Joyce research and scholarship, is due less to the Irish writer’s tenancy in the city, in life as in death, than it is to the achievements of another man, a Swiss native and Zurich local named Fritz Senn, who has devoted much of his long life to the study and promotion of Joyce’s work. Among Senn’s many publications are Joyce’s dislocutions: Essays on reading as translation (1984); Nicht nur Nichts gegen Joyce. Aufsätze über Joyce und die Welt (1999); Joycean Murmoirs (2007); and, most recently, Ulysses Polytropos (2022). Senn has founded and edited international journals, initiated Joyce symposia, and, together with Klaus Reichert, compiled the Frankfurt James Joyce Edition, in seven volumes.

The Zürich James Joyce Foundation (ZJJF), which celebrates its 40th birthday this year, was established in 1985 with financial assistance from the Schweizerischer Bankverein (today’s UBS) to house Fritz Senn’s collection of first editions, secondary literature, and Joycean memorabilia, and to allow visiting scholars to profit from Senn’s personal expertise along with the library and archive. The ZJJF holds open reading groups, typically led by Senn himself, in which participants read Ulysses and Finnegans Wake together over the course of many months, and organizes a series of talks, known as the Strauhof Lectures, by noted Joyce specialists. It hosts a translators’ roundtable and regularly stages convivial celebrations of Joyce’s work, with readings and music at Christmas and, of course, a yearly Bloomsday event every June 16, commemorating Joyce and Nora’s first assignation and the date on which Ulysses is set. Read more »

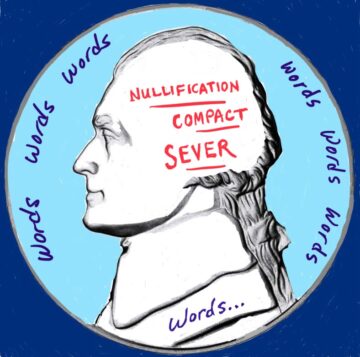

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.

One argument for the existence of a creator /designer of the universe that is popular in public and academic circles is the fine-tuning argument. It is argued that if one or more of nature’s physical constants as mathematically accounted for in subatomic physics had varied just by an infinitesimal amount, life would not exist in the universe. Some claim, for example, with an infinitesimal difference in certain physical constants the Big Bang would have collapsed upon itself before life could form or elements like carbon essential for life would never have formed. The specific settings that make life possible seem to be set to almost incomprehensible infinitesimal precision. It would be incredibly lucky to have these settings be the result of pure chance. The best explanation for life is not physics alone but the existence of a creator/designer who intentionally fine-tuned physical laws and fundamental constants of physics to make life physically possible in the universe. In other words, the best explanation for the existence of life in general and ourselves in particular, is not chance but a theistic version of a designer of the universe.

One argument for the existence of a creator /designer of the universe that is popular in public and academic circles is the fine-tuning argument. It is argued that if one or more of nature’s physical constants as mathematically accounted for in subatomic physics had varied just by an infinitesimal amount, life would not exist in the universe. Some claim, for example, with an infinitesimal difference in certain physical constants the Big Bang would have collapsed upon itself before life could form or elements like carbon essential for life would never have formed. The specific settings that make life possible seem to be set to almost incomprehensible infinitesimal precision. It would be incredibly lucky to have these settings be the result of pure chance. The best explanation for life is not physics alone but the existence of a creator/designer who intentionally fine-tuned physical laws and fundamental constants of physics to make life physically possible in the universe. In other words, the best explanation for the existence of life in general and ourselves in particular, is not chance but a theistic version of a designer of the universe. Sughra Raza. Scattered Color. Italy, 2012.

Sughra Raza. Scattered Color. Italy, 2012.