by Jonathan Kujawa

Recently, Chris Drupieski and I released a new research paper. If we were a tech company, we would announce the paper at a lavish event. There, every lemma would be amazing, every proposition would be magic, and every theorem would be world-changing.

Instead, we put it on the arXiv.

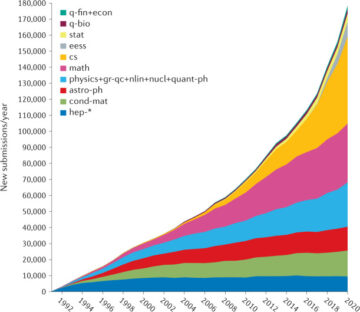

The arXiv (pronounced like “archive”) is a moderated online archive of research preprints. In large swaths of math, physics, computer science, and data science it is customary for researchers to post their latest paper on the arXiv once it’s ready for release. Indeed, the arXiv has 5,000,000+ monthly users, hosts over 2,000,000 research papers, and approximately 200,000 new papers are added each year.

Publishing on the arXiv makes the research immediately and freely available to everyone in the world. In mathematics, a paper describes the results and provides all the data and logical arguments necessary to verify and reproduce those results [1]. Anyone in the world can read my paper with Chris and decide for themselves if it is correct and use what we’ve done in their own work.

It is easy to underestimate the impact the arXiv has had on scientific progress.

There is a flywheel effect in scientific research: the more quickly new advances are shared, the faster the new results and techniques can be incorporated by other scientists into their own research. They then use this information to accelerate their own progress, share that work, and further stoke the scientific engine.

In mathematics, preprints and the arXiv play a crucial role in this flywheel.

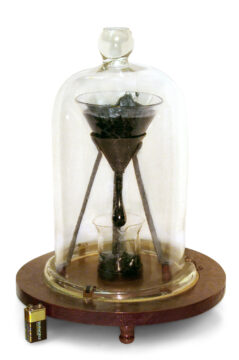

The traditional publication route runs at the pace of the Pitch Drop Experiment. Chris and I released our previous paper in October 2023 and simultaneously submitted it to a journal for consideration for publication. Roughly a year later, we got back a favorable referee’s report, made the requested changes, and sent back a revised version of the paper. It’s now been 18 months and counting, and we still await the final decision [2].

It could easily take our paper two years to go from completion to publication. This pace is not unusual in mathematics. Releasing our paper on the arXiv allows us to circumvent this process. And, indeed, for many purposes, the release of a paper to the arXiv is the real moment of publication. You are sure to be behind everyone else if you only read published papers.

Multiply by the many math papers released every year, and in a world without the arXiv you end up with thousands of years of collective delay in scientific progress [3]. Thanks to the flywheel, that delay would accumulate. The arXiv has likely put mathematical research a century or more ahead of where it might otherwise be.

Not only does the arXiv allow information to freely circulate, it also makes it monetarily free.

Academic publishers are up there with the cable companies and airlines in their outright hostility to their customer base. A university will pay many, many thousands of dollars for research journals in order for their faculty to access publications that the same faculty gave to the publisher for free. Publishers have profit margins of 30+%. It’s good business if you can get it.

Academic publishers are up there with the cable companies and airlines in their outright hostility to their customer base. A university will pay many, many thousands of dollars for research journals in order for their faculty to access publications that the same faculty gave to the publisher for free. Publishers have profit margins of 30+%. It’s good business if you can get it.

Chris and I have the benefit of working for research universities that provide extensive libraries with numerous journal subscriptions. But even we can’t always get the research articles we’d like to read. And if you’re at a smaller institution, or live in a less wealthy country, or want to do math for fun, good luck! A single research article can run you $25+, and you might need to read a dozen or more for one project. The arXiv circumvents this abomination by allowing you unlimited free downloads. It’s both free as in “free speech” and as in “free beer” [4].

Sometimes the naive optimism of the early internet actually worked out.

Of course, like any human endeavor, the arXiv is not without flaws. To keep it from being overwhelmed with questionable submissions, there are moderators who screen submissions. As Twitter and Facebook found, moderation inevitably leads to frustration.

Some complain that moderation is too light and allows too many papers through. The General Mathematics area of the arXiv has numerous submissions that are arguably marginal, and some are plainly wrong (I’m looking at you, the many proofs of P ≠ NP). It is important to remember that the arXiv is only meant to be a repository of preprints. There is no claim that the papers have received any meaningful scrutiny. Indeed, the only requirement is that a submission “be of scholarly archival interest to the communities they represent.” Sadly, the media will frequently report on an arXiv preprint as if it has been highly scrutinized by experts (this was an especially serious problem during COVID).

On the flip side, some complain that the moderation is too heavy-handed. For those, there is viXra. This is the wild, wild west of zero moderation. If you’d like to publish your proof that irrational numbers do not exist, or your two-page proof of Fermat’s last theorem, then you’ll find fellow travelers there.

If you’d like to read more about the history and inner workings of the arXiv, I recommend this article in Wired magazine and this retrospective essay by Paul Ginzparg.

Information should be free, but your time should not.

—Steve Wozniak

***

[1] Obviously, research papers are written with the expectation that readers bring a certain amount of knowledge and expertise to the table. There may be implied knowledge, missing details, and logical jumps that require experience to fill in. And even this is somewhat of a Platonic ideal; there are certainly papers where experts are skeptical about whether the missing details can be filled in.

[2] To be fair, the paper is rather intricate, and the referee read it closely, suggesting some thoughtful changes. This is no doubt a time-consuming task. Plus, journal referees work on a voluntary basis! You can’t hardly fault them for taking the time they need to take.

[3] Of course, the scientific ecosystem is not in a state of stasis. It’s easy to imagine that if the pressure release provided by the arXiv wasn’t available, the publication process itself wouldn’t be in its current state. However, even in the most ideal worlds, traditional publication would take months, and those months quickly accumulate into many years of delay.

[4] Gratis vs. Libre.

[5] Image from here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.