by Sherman J. Clark

There are many reasons, moral and prudential, not to be cruel. I would like to add another. Cruelty is bad for us—not just bad for those to whom we are cruel but also bad for those of us in whose name and for whose seeming benefit cruelty is committed. Consider our vast system of jails and prisons. Much has been said about the moral injustice of mass incarceration and about the staggering waste of human and financial resources it entails. My concern is different but connected: the cruelty we commit or tolerate also harms those of us on whose behalf it is carried out. It does so by stunting our growth.

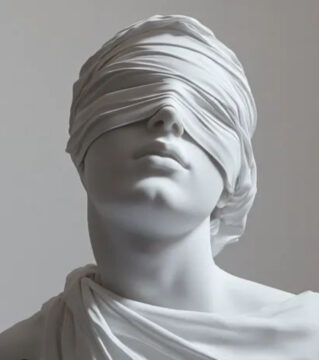

To sustain such cruelty, we must look away—cultivate a kind of blindness. We must also cultivate a kind of cognitive blurriness, accepting or tolerating tenuous explanations and justifications for what at some level we know is not OK. And in cultivating that blindness and blurriness, we may make ourselves less able to live well. It is hard to navigate the world and life well with your eyes half closed and your internal bullshit meter set to “comfort mode.”

We’ve gotten good at not seeing what’s done in our name. Nearly two million people are incarcerated in America’s prisons and jails. They endure overcrowding, violence, medical neglect, and conditions that international observers regularly condemn. We know this, dimly. The information is available, documented in reports and investigations and lawsuits. But we have developed an elaborate architecture of avoidance—geographic, psychological, linguistic—to keep this knowledge at arm’s length. We put prisons in the remote regions of our states, and prisoners in the remote regions of our minds. And we try not to think about it.

This turning away from the cruelty of mass incarceration is only one of many ways we hide from our indirect complicity in or connection to things that should trouble us. Prisons are just one particularly vivid example of ethical evasions that can dim our sight, cloud our minds, and thus in inhibit our ability to learn and growth and thrive. We perform similar gymnastics of avoidance everywhere: treating financial returns as somehow separate from their real-world origins; planning out cities so that the rich often need not even see the poor; ignoring the long-term consequences of political decisions. Each of these distances—financial, geographical, temporal—may appear natural, even inevitable, just how things work. But they’re architectures we’ve built, or at least maintain, to spare ourselves from seeing clearly. Read more »

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.

by David J. Lobina

by David J. Lobina