by Andrea Scrima

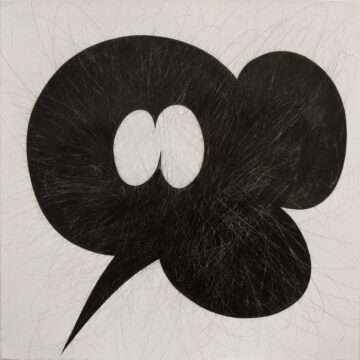

For the past ten years, Andrea Scrima has been working on a group of drawings entitled LOOPY LOONIES. The result is a visual vocabulary of splats, speech bubbles, animated letters, and other anthropomorphized figures that take contemporary comic and cartoon images and the violence imbedded in them as their point of departure. Against the backdrop of world political events of the past several years—war, pandemic, the ever-widening divisions in society—the drawings spell out words such as NO (an expression of dissent), EWWW (an expression of disgust), OWWW (an expression of pain), or EEEK (an expression of fear). The morally critical aspects of Scrima’s literary work take a new turn in her art and vice versa: a loss of words is countered first with visual and then with linguistic means. Out of this encounter, a series of texts ensue that explore topics such as the abuse of language, the difference between compassion and empathy, and the nature of moral contempt and disgust.

Part I of this project can be seen and read HERE

Part II of this project can be seen and read HERE

Part III of this project can be seen and read HERE

Images from the exhibition LOOPY LOONIES at Kunsthaus Graz, Austria, can be seen HERE

10. AWWW

I look at you and offer an encouraging smile: it’s an awkward moment. You tell me of your suffering and I feign compassion. I feel my face subtly shift as it transforms into its own mask: eyes slightly widened, brow furrowed, I gaze back at you in simulated empathy. Seated opposite me, you are stripped bare; you expose your weakness. Then something in you collects itself, grows cautious, alert suddenly to the spectacle of your unprotected state and your own vulnerable self and my detached vantage as I coolly view you. You excuse yourself, embarrassed; I assure you that there is no need for apologies.

We praise people for enduring their pain in silence; admiringly, we say that they never complain. But do we consider their loneliness as they spare us the obligation of expressing sympathy, of imagining ourselves in their place? Surely we wish no harm; surely our response is sincere: we would do anything to alleviate their suffering, or so we believe. We think of Schadenfreude as a despicable character trait. We wince at the sight of physical injury, the display of the self unraveled, unable to maintain its composure, its dignity and pride. But we are also curious, absorbed by an almost scientific interest. Finally, we give in to our fascination—so these are the symptoms of a body as it breaks down; these are the utterances of a mind as it falls apart. Safe in our perch of good health, we observe the soul in all its nakedness as it watches its future shrink before it, dissolve into the vanishing point of an unknown horizon.

Pity has little to do with compassion; it derives from the superiority we feel in a secure position and masquerades—chiefly to ourselves—the power we feel towards those in a weakened state. We feel pity when viewing the poached body of a wild beast no longer able to tear us to shreds; we’re free now to marvel at its nobility, its beauty. Pity is an indulgence we allow ourselves once a threat has been neutralized. We pity the pretty and vain when their good looks abandon them; we commiserate with the competition when they lose: it is the gladiator’s magnanimity toward a conquered opponent. Pity, however, lacks true empathy; it is the cousin of sentimentality. The former predator is reconfigured, for instance, in the child’s stuffed animal—with a ribbon around its neck and an adorable shirt that doesn’t quite cover its belly, the cuddly toy is the exemplar of kitsch—and in spite of the very real tears we shed, sentimentality, as Oscar Wilde famously quipped, is the “bank holiday of cynicism.”

14. GRIEF (SNIFF)

One of the more disconcerting observations that can be made about humans is the fact that we can go for long periods of time deceiving ourselves. We believe in the names we give to our feelings and motives and speak about them as though we knew them, or knew ourselves—until an unexpected event introduces a more complex reality. When a person’s mask falls, we assume they are aware of the discrepancy that has so suddenly been revealed; it’s a different matter altogether when we’re confronted with a part of ourselves that we’ve forgotten or have failed to see previously. A loved one dies, or we lose something that constitutes our identity, and we enter a liminal state in which we are closed off from everyone around us. Our citizenship in the “normal” world has been abruptly revoked: we can do no more than gaze out at it as though through a thick pane of glass.

As Alain Badiou, considering the figure of Stepan Trofimovitch in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Demons, wrote: “real and true grief has sometimes even made fools more intelligent, also only for a time, of course.” Grief brings a basic fact of our existence into sharp focus: that life can end at any time, and that the conditions of mortality are indifferent to the things and people we hold dear. As an emotional state, grief insists on its truth and has little tolerance for insincerity. We find ourselves acting “out of character,” exploding in a rage or sudden laughter entirely inappropriate to the solemnity of the situation, or we finally tell someone what we really think of them. It’s as though a veil had been pulled aside, enabling us to see things more clearly. We feel we’ve gained insight we will never again lose, that we’ve understood what really matters. Gradually, however, everyday life reasserts itself and we slip back into a state of self-deception.

Yet reasons for grief are readily abundant; our permeability dictates the degree to which we perceive them. Occasionally, we notice that we have a lower tolerance for the grief of others than for our own. We’re annoyed at the exceptional state they lay claim to and expect them to “snap out of it” and get back to business. In a fit of self-absorption, we recall with a pang that we too once felt what they are feeling. When the injustices of the world no longer outrage us, when we can no longer feel deeply, do we go through the motions and fall back on ethical principles? We grieve for a world we believed we could bring about; we mourn an idea we had of ourselves, lament the loss of our illusions. In the end, it’s our own selves we grieve for, the part of us that once took on the pain of the world, that felt, in a visceral way, its anguish and its sorrow.

15. INVIDIA

Envy engenders competition; it is a driving force in the market-oriented society, the urge that makes us want to keep up with the Joneses. What you have is beautiful; yet the fact that you have it and I do not makes it unbearable to me. Perhaps you worked hard for your wealth, your possessions, your status, or perhaps they were given to you unearned, like a birthright. Either way, your self-assurance protects you like a cocoon, lending you an aura of authority that lays claim to more than your share. Without giving it a second thought, you absorb the attention, the admiration, even the oxygen I too need to breathe. I despise myself for hating your natural innocence; in a gesture of goodwill I offer you my hand, and you toss your coat over my outstretched arm, mistaking me for the hired help.

The German language makes a distinction between envy as a malevolent desire to see the envied person harmed or at least lose the attribute or object of our envy, and a more benign variety that can be admitted to almost affectionately, a wistful acknowledgement to a friend that we are glad on their behalf, even though we do not share in their good fortune. Sometimes, however, envy hardens into outrage at the sight of someone enjoying a pleasure we may never know. We want to see misfortune befall them, all the more if we see them taking pleasure in the inner turmoil we are trying our best to conceal.

Envy kills. Instead of seeing ourselves for who we are, as the protagonists of our own unique lives, we become mired in comparison and find ourselves wanting. Like a form of poison, it gradually eats away at the self and makes us forget our intrinsic worth. You are envious when you detect that I have something you feel you deserve, but cannot obtain; you are envious when you see that my skills or achievements outweigh your own. Your ignorance enables you to convince yourself that my privilege is unearned or that you have a more rightful claim to it. Do not think this escapes me; I am merely quick to hide it. For your envy makes me uneasy and I do all I can to circumvent it: I downplay my achievements, my good luck, I am a master at self-deprecation, ever alert to the slightest shifts in atmosphere—but I see the dark clouds gather in your eyes. If I am superstitious, I might fear your envy in the way my forbears feared the evil eye, creating amulets and devising spells to ward off the terrible power of your malevolence. I do all that I can to protect myself, because I fear that your envy will stop at nothing, that it seeks my downfall and my demise.

16. Quo Vadis? (Where Are You Going?)

We are born into a world we have not made, but learn to navigate with the help of our caregivers and our innate capacity to learn based on the evolution of our genetic code. And we learn quickly: to protest against the things we do not like, to demand the things we want, to shamelessly push aside siblings, schoolmates, playground companions to grab whatever prize is at stake. Or have you forgotten how ruthless childhood can be? Only later do we learn to share; although adulthood teaches us better manners, these basic instincts remain.

In the King James version of the Bible, Saint Peter, encountering a resurrected Christ along the Appian Way, asks “whither goest thou?” Jesus responds that if Peter deserts his people, He will continue on to Rome to be crucified a second time, whereupon Peter takes heart and returns to meet his fate. In reminding us to reassess our decisions and to face our shame and our cowardice, the question Where are you going? urges us to come clean about the rationalizations we present to the world and to admit to ourselves our true motivations. Yet it also contains another meaning: that we are knowingly exposing ourselves to certain punishment. If we return to Rome, it is to face a danger we may have only just managed to escape. But what do we achieve when we put our lives on the line, and who will we help in doing so?

Behind the question lies another question. Peter is running not toward anything but away from persecution and, ultimately, his own execution—but in doing so he is abandoning his faith, his followers, and everything he has previously stood for. What is a life worth? And what is worth giving one’s life for? To ask this today sounds like madness; it is the language of fanatics, of zealots, of the mentally unstable. We live in a world of moral relativism in which taking an ethical stance is regarded—and scoffed at—as virtue-signaling, a bid for attention. We convince ourselves that the truth is too subtle to warrant reckless, drastic acts; that the emotions we feel—the disgust, the fear, the outrage, the self-loathing—are too roughly hewn to be mistaken for the demands of the conscience, which we imagine as something abstract and pure. Our awe at the spectacle of self-immolation turns to repulsion; unable to imagine self-sacrifice as something a person may arrive at through an act of logical reasoning, we view it as something foreign and grotesque. Quo vadis? We are called upon to consider the values we profess and ask ourselves whether we actually practice them. We mistake our equivocations for wisdom, our compromises for judiciousness. Yet behind them lie our most basic instincts, first and foremost our will to survive—stripped now of the innocence of childhood, because we have lived long enough to see the consequences of our inaction.

Part I of this project can be seen and read HERE

Part II of this project can be seen and read HERE

Part III of this project can be seen and read HERE

Images from the exhibition LOOPY LOONIES at Kunsthaus Graz, Austria, can be seen HERE