by Martin Butler

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

Google ‘loss of community’ and myriad reports and articles pop up. It’s both misleading and unhelpful, however, to frame the problem in terms of such a loss, or as a conflict between ‘I’ and ‘we’. It’s important to recognise from the outset the uncontroversial point that, like dolphins or chimpanzees, human beings are by nature social animals. The claim that we have become too individualistic can’t mean that we have somehow changed our basic nature. Since our evolution on the plains of Africa, very few Homo Sapiens have lived truly non-social lives. As individuals we are relatively puny beings, our evolutionary success largely depends on our ability to act together as a group. In one sense then, it is an inescapable fact that we all live in communities on which we depend, and it’s important to remember the simple fact that we cannot survive without cooperating with others.

The anxiety about the loss of community expressed by Putnam and others must then be concerned with something other than this deeply social nature. What exactly is this?

A general characteristic of modern industrial societies which throws light on this is the fact that our interdependence on others (as adults) has become largely divorced from our most important social bonds: families, close friends, neighbours. We all live within societies and wouldn’t last long if we didn’t, this is the locus of our interdependence on others. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019.

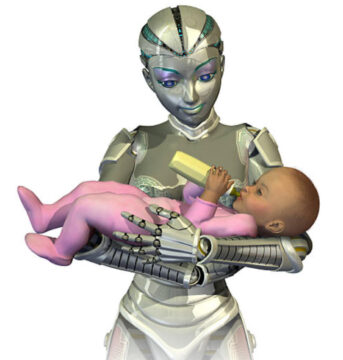

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019. At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect.

At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect. With In the New Century: An Anthology of Pakistani Literature in English, Muneeza Shamsie, the time‑tested chronicler of Pakistani writing in English, presents what is arguably the definitive anthology in this genre. Across her collections, criticism, and commentary, Shamsie has chronicled, championed, and clarified the growth of a literary tradition that is vast but, in many ways, still nascent. If there is one single volume to read in order to grasp the breadth, complexity, and sheer inventiveness of Pakistani Anglophone writing, it would be this one.

With In the New Century: An Anthology of Pakistani Literature in English, Muneeza Shamsie, the time‑tested chronicler of Pakistani writing in English, presents what is arguably the definitive anthology in this genre. Across her collections, criticism, and commentary, Shamsie has chronicled, championed, and clarified the growth of a literary tradition that is vast but, in many ways, still nascent. If there is one single volume to read in order to grasp the breadth, complexity, and sheer inventiveness of Pakistani Anglophone writing, it would be this one.

In my last

In my last

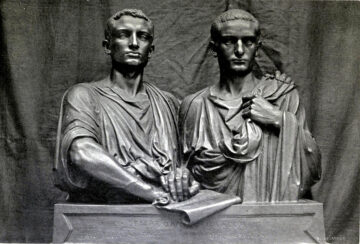

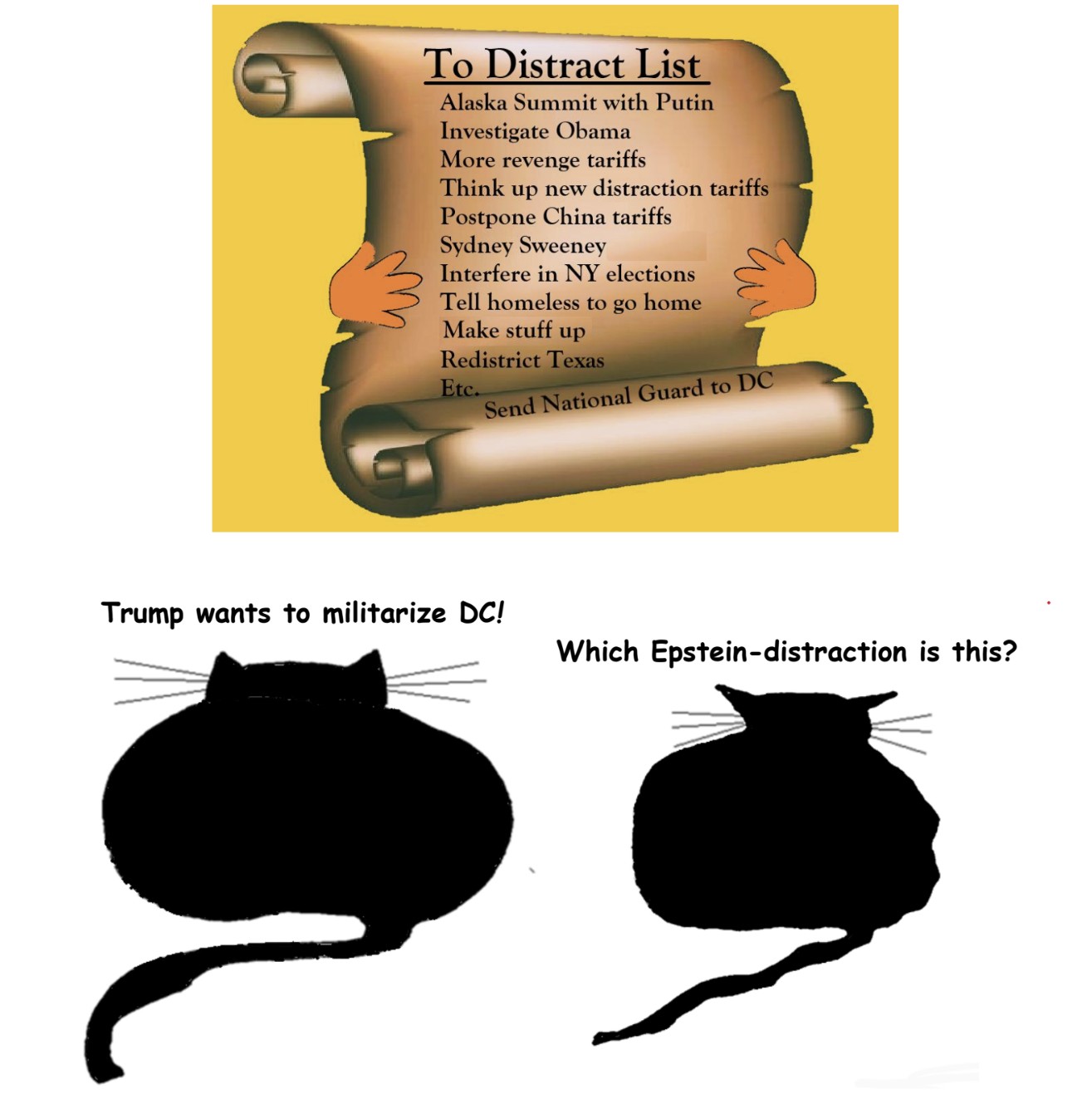

In the first part of this column last month, I set out the ways in which the separation of powers among the three branches of American government is rapidly being eroded. The legislative branch isn’t playing its part in the system of “checks and balances;” it isn’t interested in checking Trump at all. Instead it publicly cheers him on. A feckless Republican Congress has essentially surrendered its authority to the executive.

In the first part of this column last month, I set out the ways in which the separation of powers among the three branches of American government is rapidly being eroded. The legislative branch isn’t playing its part in the system of “checks and balances;” it isn’t interested in checking Trump at all. Instead it publicly cheers him on. A feckless Republican Congress has essentially surrendered its authority to the executive.

I drive in silence these days. That in itself is nothing new. For years, my solo road trips across America have featured long stretches of near silence. Nothing coming from the speakers. No talk, no music, no pleading commercials. Just the whir of the road helping to clear my mind.

I drive in silence these days. That in itself is nothing new. For years, my solo road trips across America have featured long stretches of near silence. Nothing coming from the speakers. No talk, no music, no pleading commercials. Just the whir of the road helping to clear my mind.

Junya Ishigami. Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2019.

Junya Ishigami. Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2019.