by Steve Szilagyi

I’m writing a Broadway musical about Hilma af Klint, the Swedish painter who anticipated the entire aesthetics of the 20th century before 1915. Her rediscovery in the 1980s scrambled the timeline of modern art history. My creation isn’t going to be one of those post-Lloyd Webber mega-musicals, but something more along the lines of Cole Porter or Richard Rodgers, with unforgettable songs like “I Enjoy Being a Girl.”

Why af Klint? Why Broadway? It’s not like she’s being ignored. After all, she has splashy shows at the Guggenheim Museum and the Tate Modern. The Swedes make a gorgeously respectful movie about her life (Hilma), and MoMA currently has a show of her least interesting works running till the end of September, 2025. There’s even a graphic novel (The Five Lives of Hilma af Klint by Philipp Deines).

But for all that, I still feel that people don’t get her. Af Klint isn’t some tame artist to be hung alongside stale contemporaries like Piet Mondrian and packed away in a catalogue raisonné. She’s a crazy woman, running wild with an axe through the history of art, like Carrie Nation wrecking an old-time saloon. She trashes the accepted timelines, makes a shambles of avant-garde pretensions – and I, for one, won’t be happy until I see the 20th century artistic canon lying in shreds under the feet of her gold statue in the Parthenon.

Her mad, mad world. Here’s the thing: Hilma af Klint is impossible to explain in any sensible way. Born into an upper-middle class Stockholm family, she goes to art school and has some success painting ho-hum landscapes, portraits and flowers. Then, at age 40, she seemingly loses her mind. She starts going to séances, hearing voices, and is soon in the thrall of a gang of disembodied spirits who call themselves The High Masters. Their leader, Amaliel, is the number two power in the universe. (Technically, he reports to Jesus.) Amaliel reveals knowledge to Hilma that has been hidden since the beginning of time, and orders her to write it down. He also commands her to forget everything she knows about art, and re-invent painting from scratch – under his direction.

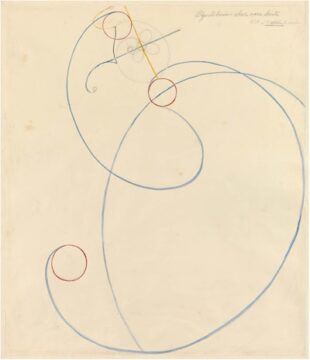

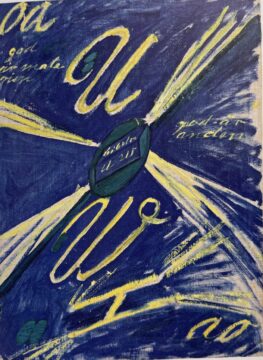

Hilma says, “Sure, why not?” and with the help of her friends, she starts churning out abstractions you might take for mature examples of Kandinsky, Malevich, Picasso, Klee, Pollock, Newman, or Frankenthaler, if you didn’t know they were painted before 1915 by someone with little knowledge or interest in what continental artists were doing. She also gets a jump on 1960s psychedelia and 70s commercial art styles. Then she designs a spiral gallery museum years before Frank Lloyd Wright’s volute structure on Fifth Avenue. She finishes the race to the end of the 20th century while every other artist is still tying on his or her shoes.

While the High Masters may be calling the shots, Hilma commands her own all-female gang. They call themselves The Five, and at the center of the circle is her bond with another strong artist, Anna Cassel. Their relationship runs deep, with emotional highs and lows that stretch over decades.

Seeking space for her visions, Hilma buys an abandoned schoolhouse and transforms it into a studio. There she unfurls canvases of staggering size — paintings unlike anything the world has ever seen.

Outwardly, she remains prim, respectable, almost conventional. But year by year she spirals further into the mystical realm. “The world is not yet ready for my painting,” she insists. And so she makes her plan: when she dies, everything will go to her nephew, with strict orders to keep it hidden for twenty years.

One day, she walks out the door onto the streets of Stockholm, is hit by a trolley, and dies at age 81. Nobody cares. She passes away an obscure old woman whose nephew is now stuck with a bunch of old boxes. The nephew stows the containers away, and forgets about them for the next fifty years. When, in the 1980s, they are finally opened, it’s like Pandora’s other box – a rolling riot of fresh, colorful happiness escapes into the world.

Let’s get serious. Now if you were writing a straight-forward biographical play about af Klint, you might want to skip the spiritual entities, or at least keep the Amaliel contingent off stage. The director of the 2022 movie Hilma followed this latter course. And you can see why. The minute a quintet of transparent figures emerge in a puff of smoke, proclaiming themselves the rulers of the universe, the work becomes fundamentally unserious.

The same thing happens when you introduce Hilma’s spiritual entities into a sober or scholarly consideration of her life and oeuvre. If you respect the artist’s intent, and accept her narrative of the creation of her art, you have to suspend disbelief in a lot of what looks like errant nonsense. Her doctrinal platform – Theosophy – was a belief system cobbled together in her own lifetime by table rappers and carnival grifters out of orientalist bits and bobs. For true believers, Theosophy proclaimed universal brotherhood through the wisdom hidden in all religions. To scoffers, it was a limp burrito of spiritual slop.

But here’s the paradox: this “slop” somehow generated revolutionary art. However soggy Theosophy appears to us now, it clearly provided af Klint with a framework radical enough to reach past every artistic convention of her time. The High Masters may have been imaginary, but their Kickapoo Joy Juice was potent enough to send af Klint zooming past the still-struggling continental abstractionists in a blistering, Roadrunner blur.

Art historians face the same dilemma Charles the Dauphin of France faced in 1429, when young Joan of Arc stood before him claiming to take orders from her own High Masters. Do you dismiss the messenger because the message sounds crazy, or do you pay attention to the results?

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Hilma? Somewhere, there are scholars and art historians poring over the tens of thousands of pages of spiritual diaries and notebooks af Klint left behind. Someday, one of these scholars will come up with what we might call a “Grand Unified Theory of Hilma” – like the astrophysicists’ long-sought unified “theory of everything”.

What would such a theory do? It would reconcile her metaphysics with the dazzling creativity of her work, and find a properly exalted place in art history for this genius who seemingly worked outside of time. But, alas, I strongly suspect that they’ll solve the puzzles of quantum mechanics before the Hilma theory is worked out.

No matter how hard you try, you can’t reconcile the many sides of af Klint. You can only juggle them. And what better stage for juggling than a Broadway musical?

For heaven’s sake, the whole medium of musical theater is based on the preposterously wonderful notion that people, at the most stressful and intensely emotional moments of their lives, should break out — not into hives, but into song.

Broadway is no stranger to interdimensional hijinks. Rodgers & Hart, Cole Porter — the great composers all tried their hand at otherworldly musicals where gods and goddesses poked their noses into human affairs. (One of them — One Touch of Venus by Kurt Weill & Ogden Nash — is actually good.)

In a world of warbling juveniles and tap-dancing soubrettes, the clash of opposites – of thesis and antithesis – produces the ridiculous.

Send in the clowns. That ridiculousness is also what makes musicals so enduringly appealing. They run on a long-established pattern, with predictable beats, and Hilma’s story slips into that pattern almost uncannily well.

For instance, by the rules of the musical, your first act must have an “I want” song — that soaring plea for escape from a dull and ordinary life, like “Over the Rainbow.” What does Hilma want to escape from? She wants to get away from the suffocating conventions of her time, the limitations placed on women artists, the spiritual bankruptcy of Sweden’s state religion. (At least, we think she should want to escape those things. Her voluminous writings are all-but silent on the women’s rights and suffrage issues of her day.)

The next necessary element is an ensemble number. This situates the characters in their social milieu. Hilma’s social life was split between The Five and her Super Friends. I picture her female companions as a vocal group like the Chordettes (Mr. Sandman), and the High Masters as their ethereal counterparts – maybe something like a celestial doo-wop group with Temptations-style choreography.

No musical can get by without comic relief. I see an opportunity in Esther, whom Hilma identifies as the sole female High Master. We’ll make Esther a chubby, Bacchic figure, always cracking wise at the expense of Amaliel. As for the big guy himself, I see Amaliel as deliberative comic figure like Jack Benny: vain, pompous, and claiming to be no older than 39,000 years.

The love story with Anna Cassel – when it comes – will occur in the half light of Scandinavian winter, with Ivory soap flakes drifting down from the catwalk high in the flies. And yes, although we have no evidence that Hilma and Anna ever so much as held hands outside of a séance, they will kiss! Because this is Broadway, where love conquers all, even when history is silent.

Just before the end, a musical must have a somber, “11 o’clock” number. Ours will give us Hilma as a forgotten old woman, carefully stowing her works into the boxes that will contain them for the next fifty years. And the finale – oh, the finale! – will take place on that day, five decades later, when the boxes are opened and her work once again sees the light of day.

One by one, we’ll see her masterpieces parade across the back wall, as the audience experiences the same thrill as those first modern viewers. Air guns shooting confetti, choral singing, ecstatic dancing, and the most rousing song in the whole show will convince the audience that the High Masters themselves are hiding in the flies, dropping soap flakes and blessings on their heads.

Waiting in the wings. All I need now is an “angel” with deep pockets to start writing checks. Until that high master comes along, I’ll imagine myself as something of a disembodied voice, hidden away in the back of the theater, auditioning dancers for the chorus line. Step forward, Anna Cassel. Tell me about yourself. And you, Amaliel – can you sing? Best of all will be that perfect moment when the right performer steps into the light and suddenly Hilma af Klint herself is standing there, ready to belt out her story to the world. Because if anyone deserves center stage, it’s this obscure visionary who heard the voices and vaulted the decades to land in our own time, a gift and a mystery for the ages. If her friends could see her now!

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.