by Fabio Tollon

What should we do in cases where increasingly sophisticated and potentially autonomous AI-systems perform ‘actions’ that, under normal circumstances, would warrant the ascription of moral responsibility? That is, who (or what) is responsible when, for example, a self-driving car harms a pedestrian? An intuitive answer might be: Well, it is of course the company who created the car who should be held responsible! They built the car, trained the AI-system, and deployed it.

However, this answer is a bit hasty. The worry here is that the autonomous nature of certain AI-systems means that it would be unfair, unjust, or inappropriate to hold the company or any individual engineers or software developers responsible. To go back to the example of the self-driving car; it may be the case that due to the car’s ability to act outside of the control of the original developers, their responsibility would be ‘cancelled’, and it would be inappropriate to hold them responsible.

Moreover, it may be the case that the machine in question is not sufficiently autonomous or agential for it to be responsible itself. This is certainly true of all currently existing AI-systems and may be true far into the future. Thus, we have the emergence of a ‘responsibility gap’: Neither the machine nor the humans who developed it are responsible for some outcome.

In this article I want to offer some brief reflections on the ‘problem’ of responsibility gaps. Read more »

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around

Aqui Thami. Resisters, 2018.

Aqui Thami. Resisters, 2018. I can’t sing. Or so I always thought. A notorious karaoke warbler, I would sometimes pick a country tune, preferably Hank Williams, so that when my voice cracked, I could pretend I was yodeling. Then one night, I stepped up to the bar’s microphone and sang a Gordon Lightfoot song.

I can’t sing. Or so I always thought. A notorious karaoke warbler, I would sometimes pick a country tune, preferably Hank Williams, so that when my voice cracked, I could pretend I was yodeling. Then one night, I stepped up to the bar’s microphone and sang a Gordon Lightfoot song.

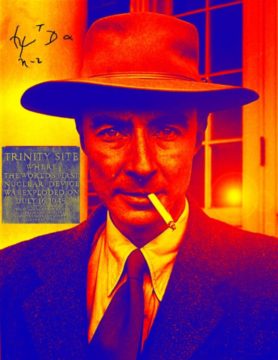

My father’s mother—Annie Newman, my grandmother or Bubbi—was born Hannah Dubin in a shtetl in what is now Ukraine a few years before the Great War. One of her earliest recollections—in addition to the image of her own grandmother hiding in a baby carriage to escape marauding Cossacks—was of being able to see troop movements from the roof of her house, presumably during the Russian Imperial Army’s advance against Austria-Hungary, an engagement that occurred in Galicia, farther to the west, in 1914. Much later, in the aftermath of the nuclear accident in Chernobyl in 1986, when that obscure place was suddenly on everyone’s lips, she began recalling that her village, which she called Priut, in a region she referred to by its Russian name as Екатеринославская губернія, or Yekaterinoslavskaya guberniya—the Yekaterinoslav Governorate, a province of the Russian Empire—was not far from that site, which had now become infamous for a catastrophic meltdown.

My father’s mother—Annie Newman, my grandmother or Bubbi—was born Hannah Dubin in a shtetl in what is now Ukraine a few years before the Great War. One of her earliest recollections—in addition to the image of her own grandmother hiding in a baby carriage to escape marauding Cossacks—was of being able to see troop movements from the roof of her house, presumably during the Russian Imperial Army’s advance against Austria-Hungary, an engagement that occurred in Galicia, farther to the west, in 1914. Much later, in the aftermath of the nuclear accident in Chernobyl in 1986, when that obscure place was suddenly on everyone’s lips, she began recalling that her village, which she called Priut, in a region she referred to by its Russian name as Екатеринославская губернія, or Yekaterinoslavskaya guberniya—the Yekaterinoslav Governorate, a province of the Russian Empire—was not far from that site, which had now become infamous for a catastrophic meltdown.  A dear friend of mine recently passed away unexpectedly. He had recommended I read Viktor Frankl’s

A dear friend of mine recently passed away unexpectedly. He had recommended I read Viktor Frankl’s

In the typical American city where we live, the average commute time is 78 minutes a day and 97.5% of

In the typical American city where we live, the average commute time is 78 minutes a day and 97.5% of  The

The