by Dwight Furrow

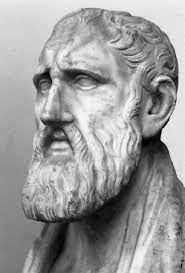

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice. Some estimate membership in these communities at about 100,000 participants. Stoicism has also played a seminal role in the development of cognitive/behavioral therapy in psychology.

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice. Some estimate membership in these communities at about 100,000 participants. Stoicism has also played a seminal role in the development of cognitive/behavioral therapy in psychology.

The puzzle is why Stoicism is now having its moment—because it is genuinely weird.

To be sure, Stoic ethics gives some good advice. One central tenet is that we place far too much value on external things such as wealth, popularity, or prestige at the expense of moral virtue. In an age of celebrity worship, groveling for likes on social media, and a mad dash for cash, none of which does much to promote happiness, we could surely use more focus on what really matters in life. But this sort of advice isn’t unique to Stoicism. It is hard to imagine any mainstream ethical theory not condemning our fascination with bling, careerism, and greed. Nevertheless, the Stoic reasoning on these ethical matters is distinctive and important because it deeply shapes the practical advice that has made it so popular.

According to Stoic doctrine, the reason why external things should be devalued is because we have little control over the circumstances that make them possible. We can’t control the economy or how others perceive us. Most of us have very little influence over world events that deeply impact our lives. Even personal matters like our health are ultimately not up to us; nature will take its course. When we focus on matters over which we have little control, we naturally react to failure with feelings of frustration, anger, and fear. These negative emotions destroy personalities and relationships and undermine happiness. Worrying about matters we can’t control saps energy and attention sabotaging our ability to act effectively. Thus, we should avoid over-reacting to adverse events. They are caused by a mistake in judgment—assuming we are in control when in fact we aren’t. Again, this is sound reasoning and good advice, but Aristotelians, Kantians, and even some utilitarians would agree.

However, the Stoic prescription for a good life is not simply to rebalance our lives by making external goods less central to them. External goods are not only of lesser importance. They do not count as genuine goods at all, according to Stoic wisdom. We should, according to Stoics, be utterly indifferent to them and not react emotionally when bad fortune befalls us or others. And thus we should avoid positive emotions as well. Joy, elation, great anticipation, feelings of sympathy, even feelings of love if the object of love is outside our control are equally indefensible. This is the source of the well-known Stoic claim that all emotions are bad and without rational justification. In all cases of strong emotion, we are assigning value to something that in fact has no value.

The only thing one should care about, for the Stoic, is moral virtue. We should observe nature and discover what human beings are designed to be and do and act accordingly. When we observe nature, we discover that we should try to secure enough to eat and otherwise stay healthy, form relationships appropriate to our species, care for our children as well as others who depend on us, and treat all human beings with the respect rational beings deserve. These are rigorous duties that we must attempt to discharge in our actions without fail. But whether we succeed or not in bringing about the intended outcome is a matter of indifference. We are not in control of outcomes, only intentions, and because we should be indifferent to outcomes, the good person who acts for the right reasons cannot be harmed.

Thus, we are to protect our children from harm and do so with great courage. We should nurture them with as much energy and commitment as we can muster. But should we fail, if our children should die despite our efforts, we should not grieve or be angry at ourselves or the world for this outcome. We should accept this outcome with equanimity. When I said Stoicism was weird, this is what I had in mind.

The view that all emotions are irrational and that, as rational beings, we ought to be utterly indifferent to the outcome of our actions and the actions of others is counter-intuitive, to say the least, and seems contrary to any reasonable account of human nature or well-being. Thus, Stoicism incurs a heavy burden; if we are to take it seriously it must provide very compelling reasons for adopting such an extreme view.

Unfortunately, their reasons are less than compelling. The Stoics taught that reality consists of a world-mind (variously referred to as God or Nature) which directly controls every event via universal principles of reason (logos) in order to maintain a maximally ordered and beautiful world. Thus, all of reality takes shape via events that are perfectly ordered, integrated, and efficient at sustaining the world organism over time. Every event that occurs in the universe is designed by this world-mind to bring about the best possible state of affairs. Human beings are also rational creatures, and it is our duty to assist the world-mind as best we can. Thus, we should intend in our actions to always do what duty requires and what nature reveals about the world-mind’s intentions. But only the world-mind knows whether our intended outcomes really serve the greater good. Thus, when we fail to achieve what we intend, it is because the world-mind decided that our actions did not conform to the best overall state of affairs. Only the world-mind’s rational plan and our intentions to contribute to it count as good. The consequences of all events, to each of us as individuals, are trivial in comparison and we should pay them no mind. The death of one’s child is a loss of no consequence since it was part of the world-mind’s comprehensively good plan.

However much this might have been persuasive to ancient Greeks and Romans, there are no philosophically sound reasons for endorsing the Stoic notion of a providential God or a teleologically governed universe that always aims for the best possible state of affairs. Stoic ethics rests on metaphysical nonsense.

To be fair, most defenders of modern Stoicism argue that these antiquated, metaphysical claims can be jettisoned without harming their ethical prescriptions. However, without that notion of God/world-mind, what is distinctive about Stoic ethics collapses. Without the idea of a providential nature that ensures even the worst personal tragedies are “for the best,” we have no reason to be indifferent to what happens. Without the idea that human reason partakes of divine reason making us duty bound to advance God’s plan, the idea that one’s virtue is all that matters, and that the good person cannot be harmed, lacks support.

Thus, modern Stoicism is left to defend itself by pointing to the psychological benefits of deep reflection on one’s attitudes about values and rigorous scrutiny of excessive emotional responses to conditions outside our control. No doubt these psychological benefits are real. But philosophically there isn’t much to modern Stoicism that could not comfortably fit into a variety of contemporary ethical frameworks that emphasize qualities of character as the locus of moral reflection. What is distinctive about Stoicism is indefensible; what it shares with other ethical theories is better supported elsewhere.

As a set of practices that aid reflection and a hyper-focus on only what we can control, Stoicism no doubt advances the cause of serenity and may support effective psychotherapy. But philosophically, it is hard to see what recommends it. In the current debates about philosophy as a way of life, to which modern Stoicism contributes, it is important to know if the debate is about philosophy or about philosophically-inspired therapy.

For more on philosophy as a way of life visit Philosophy: A Way of Life.