by Ashutosh Jogalekar

“Giving up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879”, by Noel Perrin

In 1543, a small Chinese pirate sloop with two Portuguese arquebusiers on it sailed into Tanegashima island in Japan. The local feudal lord, Tokitaka, was so impressed when he saw one of the arquebusiers shoot a duck that he promptly ordered two of the guns for a price that was to go down 500-fold over the next seventy years. The same day he ordered his swordsmith to repurpose his skills for manufacturing the new weapon.

That dramatic reduction in price shows the impact the gun had on Japan. In the next hundred years, Japanese gun manufacturing achieved a level of prominence and expertise that in many ways exceeded anything in the West; for instance, the Japanese devised the simple and yet unique expedient of protecting their gunpowder in a water-resistant pouch to prevent a matchlock fizzle, allowing them to take guns into battle comes rain or shine. Japanese metallurgy was also second to none, with cheap and yet effective Japanese copper being the envy of the West. The advantages of the gun became very apparent very quickly; in 1575 at the Battle of Nagashino, for instance, Oda Nobunaga handily defeated Takeda Katsuyori’s cavalry by mowing them down like a scythe with a sophisticated pattern of gunfire. Other engagements followed, including a war with Korea, where the practical utility of the gun was left in no doubt. It looked like, from almost any angle, Japan was set to lead the world in advanced gun warfare for the foreseeable future.

And yet after a hundred years, the reduction of gun warfare was equally dramatic, so much so that the small trickle of Western observers who managed to make it to the island nation after Japan had banned Christians thought that the country existed in a state of primitive ‘Arcadian simplicity’, completely innocent of modern weaponry. Little did they know the history which Dartmouth professor Noel Perrin recounts in this lively volume. Japan remains perhaps the only example of an advanced, intelligent nation that sampled guns and then willingly gave them up for hundreds of years. Perrin explains the why and the how here and speculates on why that might hold some lessons for our own obsession with new weapons and technology.

The “how” is founded on a few key factors, most of which are unique to Japanese culture and history. One was geopolitical. After a wave of conversions by Portuguese and Spanish Jesuits, Japan had had enough of Western influence; she had her hands full anyway with the constant infighting between its hundreds of principalities. Combined with the fact that the country was an isolated, insular island with both little need to defend itself against outsiders and an aversion to Western ideas, she simply saw no urgency to adapt to new weapons in an arms race unlike that in Europe.

The second factor was cultural. In a nation with strictly delineated lines of hierarchy, the fact that a mere farmer with a gun could suddenly outdo and disarm a highly trained swordsman from a higher social and economic class was disconcerting. This attitude was very different from that in the egalitarian United States where it was for just this reason that guns were considered the great leveler; at Lexington and Concord, at Trenton and Saratoga, it was precisely because farmers and silversmiths and cobblers could beat highly trained British regulars at their own game that guns became popular. The case was very different in Japan where a warrior code had developed for centuries and where proficiency with weapons scaled with notions of social rank.

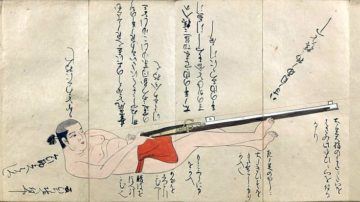

It was this warrior code that provided the third big reason for the country’s disillusionment with guns, an aesthetic one that may have exceeded any practical one. Anyone who has visited Japan knows the Japanese love for beauty and order in all things big and ordinary. The aesthetic extended to the highest order when it came to swords. Even people with a cursory knowledge of the country know the legend of the Japanese samurai, a social class whose manners and weaponry were promoted to high art. For the samurai, social rank and prominence and proficiency with the sword went hand in hand. The sword was not a weapon but a part of their body and soul; the Japanese still speak of self-indulgent behavior as “the rust of my body”. Everything from the ornate tooling on the sheath and blade to the precise actions orchestrated with every stroke signified tradition steeped in centuries-old reverence. Any dent in this tradition, a dent provided by the very ordinary, in comparison, movements executed with a gun, would be considered downright vulgar. Perrin talks about how a 17th century Japanese manual was almost apologetic in its description of the movements a marksman would have to perform in order to load and fire his weapon. When it came to beauty over utility, at least in the context of swords and guns, the Japanese chose beauty every time. It was again very different in the United States where the practical American mind forged ahead with interchangeable parts and assembly lines. One of my father’s favorite sayings was, “Beauty and utility are often inversely proportional to each other”. Both Japan and the United States seem to have followed this rule.

This combination of geopolitical, cultural and aesthetic factors effectively spelt the doom of the gun. And yet like the rise and fall of any technology, one cannot point to any single moment when the entire country disarmed. It is this “how” of disarmament explored in the book that makes it more than just a historical curiosity. The Japanese were encouraged to give up their guns through a combination of financial incentives and pure shrewd guile. The financial incentives were more an edict than incentives. At the beginning of the 17th century, there were two principal gun manufacturing centers in Japan, one in Nagahama and one in Sakai. In 1607, the Tokugawa shoguns summoned the leading gun and swordsmiths and told them to consolidate all their activities in Nagahama. More crucially, they were elevated to samurai and asked to move away from gun making. Henceforth, all guns and powder would have to be approved by Tokyo, effectively establishing a government monopoly. Other gun makers around the country soon had to either move to Nagahama and Sakai or give up gun making. In effect, it wasn’t so much that the shoguns were turning guns into swords as they were turning gunsmiths into swordsmiths. By 1675 the monopoly was well-established, and the flow of guns had slowed to a trickle. In a country where there were half a million samurai, guns very soon ceased to be a decisive factor in warfare. Similar edicts had been passed in European nations, by Henry IV in France, for instance. But in no European country were they as permanent.

The shrewd guile could be shrewd indeed. In a characteristically Japanese gesture, a certain Lord Hideyoshi proclaimed in 1587 that he was going to build a statue of the Buddha that would reach to the sky and dwarf every other statue in existence. Many tons of iron would be needed for it. Even more would be needed for the giant temple that was to surround it. Farmers, monks and samurai were all “requested” to turn their weapons into sacred metal. The ruse seems to have worked for encouraging a good number of commoners to give up their weapons.

It was thus that the gun effectively disappeared from the Japanese battle scene until the late 19th century. After Commodore Matthew Perry opened the country to trade and foreign statecraft in 1855, the Japanese were quick to recognize the value of firearms, and by the end of the century their development of weaponry kept track with similar developments in Europe and the United States. But not without resistance, of course, as demonstrated by the last gasp of the samurai – their spirited attack against modernism and the Japanese government in the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. Reverting back to the gun after having reverted back to the sword proved painful after all.

What lessons can we in the 21st century learn from this rare example of a country disarming and actively rejecting advanced weaponry? Can we apply it to the technologies that threaten us in multiple ways, ones like nuclear weapons and social media? Even today acquiring a gun in Japan is an extensive, grueling process that only grants citizens possession of shotguns and air rifles and bans all handguns and semi-automatic and automatic weapons. The question of guns in the United States seems especially painful and urgent because of the horrific ways in which guns are being put to use here. Japan’s case is especially striking because this wasn’t a case of a nation giving up all modern technology and becoming Luddites. In fact, Perrin makes the case that until the 17th century, on technological fronts as diverse as aqueduct construction and papermaking, metallurgy and food storage, the West was merely playing catch up to Japan (he does seem to overstate the case: Did the Japanese really invent the equivalent of Kleenex back then?). For most of us in the 21st century, Japan is in fact synonymous with advanced technology. The gun therefore does seem to have been a rare bit of new technology that the Japanese gave up.

Unfortunately, it’s not clear to me if we can draw many direct lessons. Japan was back then, as it is now, a unique culture without parallel. The combination of social hierarchy and aesthetic reverence that existed there does not have a clear analog in America or in most other countries for that matter. More importantly as mentioned above, guns are baked into this country’s founding, much as swords were baked into Japan’s founding. Perhaps someone can find an appropriate religious or political figure of acclaim and worship from the past whose statue would inspire gun owners in this country to beat their metaphorical swords into plowshares, but it seems unlikely.

What we can take away from Japan’s example are a few general lessons. Firstly, within the constraints of the feudal hierarchy, the Japanese government offered gunmakers enough incentives for them to consider giving up their old trade and embracing a new one. Perhaps something similar could be done, in a more modern form, with gun manufacturers in this country. Importantly, they need to be incentivized to manufacture something that, just like guns, is cheap and in high demand. An interesting analogy comes from the national labs which worked on nuclear weapons. When the Cold War ended and their existence seemed threatened because they no longer had to spend so much effort and money on these weapons, the government gave them new toys and tools and the accompanying budget – over time, the labs became leaders in fields like supercomputing, laser fusion and genomics.

There are also examples in our time of nations giving up nuclear weapons, with South Africa, Sweden and South Korea all being striking case studies. In all these cases, internal cultural factors combined with security guarantees by other nations made the decision possible. The fact is that the right incentives can effect change, although the problem with the gun manufacturers is one of sheer demand.

This brings us to the second, subtle and potentially decisive factor. Ultimately the Japanese gave up the gun because they found it useless. Not useless in a military sense because it clearly was not. Rather, the gun was useless for the Japanese code of honor, for Japan’s social organization, for the preservation of a proud and unique Japanese culture. The Japanese gave up the gun when they recognized that it does not quite line up with their identity, with their dignity as a people. Can something similar happen in the United States? Would the United States give up the gun or at least drastically scale back when its people realize that the freedom to possess a highly advanced assault rifle is not consistent with the ideals of equality, freedom and value of individual lives that are protected in the Constitution, especially when the individual lives are those of children with untold potential? Perhaps this country will give up its obsession with guns when it realizes that if it truly believes that all men are created equal, it will have to believe that some technologies of death and destruction are more unequal than others. One can hope.