by Chris Horner

No man is a hypocrite in his pleasures —Dr Johnson

Without music life would be a mistake —Nietzsche

Music started for me with whatever was blaring out of the radio, and later those 45 rpm ‘single’ records that were the main vehicles of listening pleasure for teenagers in the late twentieth century. I heard a lot of that rather than listened to it. Listening really started with the ‘long player’ or album: 40 minutes or so over two sides of a black disc with a cover that, if you were lucky, didn’t look too bad when you gazed at it.

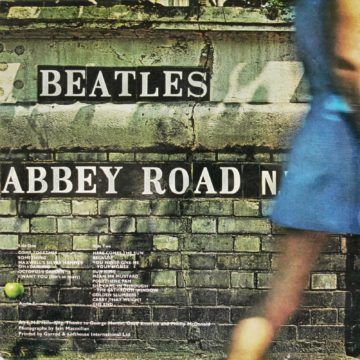

The first album I owned was a birthday present: Abbey Road, the final Beatles recording. Having nothing else to play, this got a lot of spins, first through the big speakers of my parents ‘Rigonda Stereo Radiogram’, then with the earphones plugged into the back with the lights off. In a private darkness the music and the lyrics were undisturbed by the banality of our front room, and the thing became something I knew by heart, images and melodies imprinted like a recurring, waking dream. Only the pleasure principle mattered: I has no idea whether I was supposed to like this stuff, I just did.

More followed, and my teenage self was pleased to find The Band and Bob Dylan was not quite so popular with my peers, which became an important point for my 16 year old self in setting out an identity. Perhaps this was a fall from the Eden of simple pleasure in the music, for now what others thought became a consideration. For another decade it was ‘Pop’, ‘Rock’, or whatever we call the music that the was all around us. Much of it was tiresome stuff after a few listens but some of it- the Beatles would be a good example – had such artistry, wit and inventiveness to as to retain my loyalty. I could still turn the lights off and really listen. It was never only background music.

Still, I had become rather sated with this musical diet by the time I reached my late twenties. I still listened and bought but not with the enthusiasm of discovery I had once had. What was wrong? Perhaps the music had lost some of its quality, but really, I think I had become bored. There didn’t seem to be enough in pop music to hold my attention or spark my imagination – the familiar chords, recycled tunes, boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl lyrics. And so to jazz, which seemed to have more to offer. But how did I know it did, and how did I come to like it?

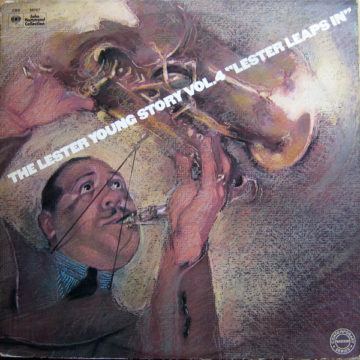

Listening now had a stage or obstacle to pleasure: getting used to a new music. While rock/pop can need a few listens to really work on us, we generally get a sugar rush of pleasure quite quickly, if we are going to get it at all. But with jazz it was different – the albums I cautiously borrowed rather than bought, of Thelonious Monk, Charlie, Parker and Miles Davis needed work. I wonder what made me persist. Where was the damned tune for one thing? Then why did it disappear so quickly into all those strange and discordant noises? Pleasure wasn’t immediate, but had to be achieved: ‘acquired taste’. I had to learn to be patient, before the music would seem less like a stranger and more like a friend. Which it did, eventually. One of the clearest memories of sheer aesthetic delight was hearing Lester Young’s solo on Billie Holiday’s recording of ‘All of Me’. That experience seems to just happen without effort, but it was surely true that I had already learned how to find pleasure in a tenor saxophone solo.

Inevitably, it seems now, I found my way to ‘classical music’. Perhaps emboldened by my new found ability to listen to stuff I couldn’t immediately hum, I worked my way through Mozart’s piano concertos. Again, though, there was step away from the sheer rush of pleasure that seemed to require no effort with the Beatles. I had to really attend, and for a much longer time span than before. I got books on ‘how to listen to classical music’, I drew diagrams to get myself clear about sonata principle and modulations. I went to concerts, to opera, to lieder, to chamber music. It’s hard to pinpoint why I wanted to put in all that work. Perhaps I was just establishing myself as an educated fellow who was too good for the music of his youth. But I still loved the Beatles and Lester Young, along with Beethoven and Mozart.

Inevitably, it seems now, I found my way to ‘classical music’. Perhaps emboldened by my new found ability to listen to stuff I couldn’t immediately hum, I worked my way through Mozart’s piano concertos. Again, though, there was step away from the sheer rush of pleasure that seemed to require no effort with the Beatles. I had to really attend, and for a much longer time span than before. I got books on ‘how to listen to classical music’, I drew diagrams to get myself clear about sonata principle and modulations. I went to concerts, to opera, to lieder, to chamber music. It’s hard to pinpoint why I wanted to put in all that work. Perhaps I was just establishing myself as an educated fellow who was too good for the music of his youth. But I still loved the Beatles and Lester Young, along with Beethoven and Mozart.

Listening, I find, is a more complex thing than it seemed when I just sat back in the dark in my youth. But was I ever an innocent ear? I was the right age and in the right place for pop music – music my parent’s generation found quite strange and alienating. It seemed effortless, but I was ready to find pleasure in it. I don’t think pleasure in music, and maybe much else, is a simple thing at all: we need to be willing to find it. Nietzsche is good on this:

Listening, I find, is a more complex thing than it seemed when I just sat back in the dark in my youth. But was I ever an innocent ear? I was the right age and in the right place for pop music – music my parent’s generation found quite strange and alienating. It seemed effortless, but I was ready to find pleasure in it. I don’t think pleasure in music, and maybe much else, is a simple thing at all: we need to be willing to find it. Nietzsche is good on this:

One must learn to love.— This is what happens to us in music: first one has to learn to hear a figure and melody at all, to detect and distinguish it, to isolate it and delimit it as a separate life; then it requires some exertion and good will to tolerate it in spite of its strangeness, to be patient with its appearance and expression, and kindhearted about its oddity:—finally there comes a moment when we are used to it, when we wait for it, when we sense that we should miss it if it were missing: and now it continues to compel and enchant us relentlessly until we have become its humble and enraptured lovers who desire nothing better from the world than it and only it.

Its not as if there is a kind of grim effort that later pays you back. The act of exploration and discovery is part of what keeps me coming back to a piece of music, and if it takes longer with Mahler or Wagner than it did with the Beatles, so be it. Pleasure has an important role, of course, but it isn’t the whole story.

It became something that provided another dimension of experience, something more like engagement than escape. And perhaps ‘pleasure’ isn’t quite the right word for all that it is to me. Music, like the other arts, connects to the whole person, to the life one lives – and so it has something to say to us about grief, too, and about the longing for something better, something other than the cruelty and drudgery in so much of life. Also also, for me at least, an invitation to something resembling love. As Nietzsche concludes:

But that is what happens to us not only in music: that is how we have learned to love all things that we now love. In the end we are always rewarded for our good will, our patience, fair-mindedness, and gentleness with what is strange; gradually, it sheds its veil and turns out to be a new and indescribable beauty:—that is its thanks for our hospitality. Even those who love themselves will have learned it in this way: for there is no other way. Love, too, has to be learned. [1]

[1] The Gay Science, S. 334