by Steven Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

Whether you love, hate, or tolerate Tesla may say something about the era you grew up in.

Every generation, when it reaches a certain age, makes two proclamations: Saturday Night Live used to be funnier, and “kids these days” are lazy and stupid.

Every generation, when it reaches a certain age, makes two proclamations: Saturday Night Live used to be funnier, and “kids these days” are lazy and stupid.

Neither claim is true, of course, but they feel true. We members of Generation X insist SNL isn’t as good as it was, but that’s because they aren’t making jokes for us any more. Their audience now consists largely of Millennials, who have a unique sense of humor shaped by the age in which they were raised. That younger audience isn’t either lazy or stupid, either. Millennials work hard, but in different ways, and they know different things than we do as well.

Still, there are meaningful differences between Gen Xers and Millennials, and one of those differences has become particularly stark of late: our tolerance for moral ambiguity.

As Gen Xers, we grew up in a world in which our favorite sports heroes were discovered taking steroids, and we had to figure out how to keep rooting for them anyway. A world in which bona fide heroes like Senators John Glenn and John McCain could get caught up in a major political scandal and still get re-elected. A world in which our own idealistic (and idealized) Baby Boomer parents entered their peak earning years and started voting for tax cuts instead of justice. We learned to distrust everything and everyone: even those we loved.

We also learned to hold multiple conflicting opinions at the same time. We need more people of color on the Supreme Court AND Clarence Thomas harassed Anita Hill AND the accusations against him played into racist tropes about Black men. Bill Clinton abused his power in having a tryst with Monica Lewinksy AND we shouldn’t portray Lewinsky as a powerless pawn unable to make her own choices AND Clinton’s politics were generally favorable to women AND he was prosecuted by other White men who were equally (or more greatly) compromised.

Life taught us to doubt the existence of pure “good” and “bad.” We came of age in a morally ambiguous world. Millennials, by contrast, came of age in a morally bankrupt world. Read more »

I think of Pearl S. Buck and end up thinking of William F. Buckley. I think of

I think of Pearl S. Buck and end up thinking of William F. Buckley. I think of  In late March the United Nations adopted a landmark

In late March the United Nations adopted a landmark

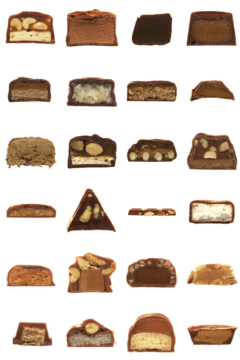

The term “gastronomy” has no agreed-upon, definitive meaning. Its common meaning, captured in dictionary definitions, is that gastronomy is the art and science of good eating. But the term is often expanded to include food history, nutrition, and the ecological, political, and social ramifications of food production and consumption. For my purposes, I want to focus on the conventional meaning of gastronomy for which that dictionary definition will suffice.

The term “gastronomy” has no agreed-upon, definitive meaning. Its common meaning, captured in dictionary definitions, is that gastronomy is the art and science of good eating. But the term is often expanded to include food history, nutrition, and the ecological, political, and social ramifications of food production and consumption. For my purposes, I want to focus on the conventional meaning of gastronomy for which that dictionary definition will suffice.

One of the most interesting debates within the larger discussion around large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 is whether they are just mindless generators of plausible text derived from their training – sometimes termed “

One of the most interesting debates within the larger discussion around large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 is whether they are just mindless generators of plausible text derived from their training – sometimes termed “

Misha Japanwala. Breastplate, ca. 2018.

Misha Japanwala. Breastplate, ca. 2018.

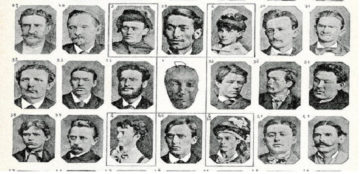

When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”

When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”