by Ashutosh Jogalekar

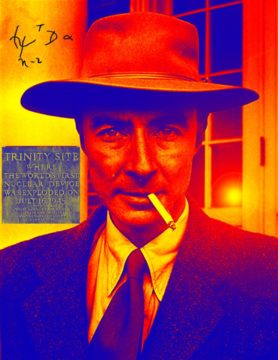

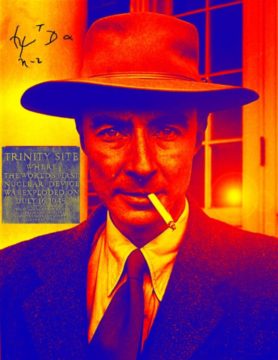

This is the fourth in a series of posts about J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life and times. All the others can be found here.

Robert Oppenheimer, said Hans Bethe, “created the greatest school of theoretical physics America has ever known.” Coming from Bethe, a physicist of legendary stature who received the Nobel Prize for figuring out what makes the stars shine and who published papers well into his nineties, this was high praise. Before Oppenheimer, it was almost mandatory for young American physics students to go to Europe to study at the feet of masters like Bohr or Born. After Oppenheimer brought back the fire from the continent, they only had to go to California to bask in its glow. Today, while Oppenheimer is most famous as the father of the bomb, it is very likely that posterity will judge his creation of the American school of modern physics as his most important accomplishment.

When he graduated from Göttingen with his Ph.D. in 1927, Oppenheimer’s reputation preceded him. He received ten job offers from universities like Harvard, Princeton and Yale. He chose to go to the University of California, Berkeley. There were two reasons that drew him to what was then a promising but not superlative outpost of physics far from the Eastern centers. Berkeley was, in his words, “a desert”, a place with enormous potential but one which did not have a flourishing tradition of physics yet. The physics department there had already hired Ernest Lawrence, an experimentalist who would become, with his cyclotron, the father of ‘big science’ in the country. Now they wanted a theorist to match Lawrence’s experimental acumen. Oppenheimer who had proven that he could hold his own with the most important physicists in Europe was a logical choice. Read more »

Allison Elizabeth Taylor. Only Castles Burning, 2017.

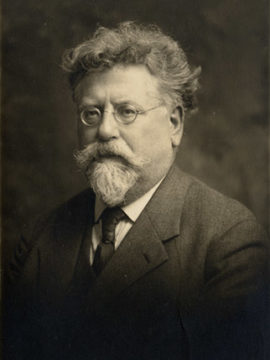

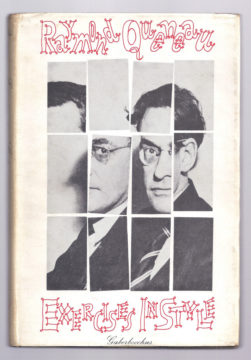

Allison Elizabeth Taylor. Only Castles Burning, 2017. Raymond Queneau was a French novelist, poet, mathematician, and co-founder of the Oulipo group about

Raymond Queneau was a French novelist, poet, mathematician, and co-founder of the Oulipo group about

Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of

Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite.

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite. Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.

Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.