Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Digital photograph.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Digital photograph.

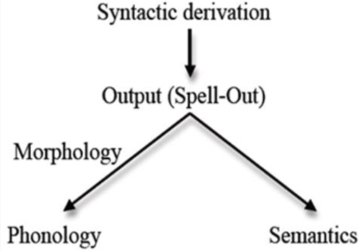

by David J. Lobina

The hype surrounding Large Language Models remains unbearable when it comes to the study of human cognition, no matter what I write in this Column about the issue – doesn’t everyone read my posts? I certainly do sometimes.

Indeed, this is my fourth, successive post on the topic, having already made the points that Machine/Deep Learning approaches to Artificial Intelligence cannot be smart or sentient, that such approaches are not accounts of cognition anyway, and that when put to the test, LLMs don’t actually behave like human beings at all (where? In order: here, here, and here).[i]

But, again, no matter. Some of the overall coverage on LLMs can certainly be ludicrous (a covenant so that future, sentient computer programs have their rights protected?), and even delirious (let’s treat AI chatbots as we treat people, with radical love?), and this is without considering what some tech charlatans and politicians have said about these models. More to the point here, two recent articles from some cognitive scientists offer quite the bloated view regarding what LLMs can do and contribute to the study of language, and a discussion of where these scholars have gone wrong will, hopefully, make me sleep better at night.

One Pablo Contreras Kallens and two colleagues have it that LLMs constitute an existence proof (their choice of words) that the ability to produce grammatical language can be learned from exposure to data alone, without the need to postulate language-specific processes or even representations, with clear repercussions for cognitive science.[ii]

And one Steven Piantadosi, in a wide-ranging (and widely raging) book chapter, claims that LLMs refute Chomsky’s approach to language, and in toto no less, given that LLMs are bona fide (his choice of words) theories of language; these models have developed sui generis representations of key linguistic structures and dependencies, thereby capturing the basic dynamics of human language and constituting a clear victory for statistical learning in so doing (Contreras Kallens and co. get a tip of the hat here), and in any case Chomskyan accounts of language are not precise or formal enough, cannot be integrated with other fields of cognitive science, have not been empirically tested, and moreover…(oh, piantala).[iii] Read more »

by John Allen Paulos

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.

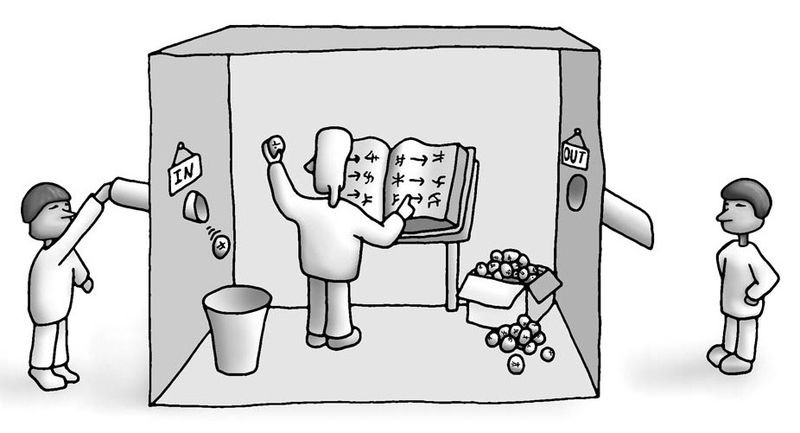

Whatever its usefulness, we naturally wonder whether CharGPT and its near relatives understand language and, more generally, whether they demonstrate real intelligence. The Chinese Room thought experiment, a classic argument put forward by philosopher John Searle in 1980, somewhat controversially maintains that the answer is No. It is a refinement of arguments of this sort that go back to Leibniz.

In his presentation of the argument (very roughly sketched here), Searle first assumes that research in artificial intelligence has, contrary to fact, already managed to design a computer program that seems to understand Chinese. Specifically, the computer responds to inputs of Chinese characters by following the program’s humongous set of detailed instructions to generate outputs of other Chinese characters. It’s assumed that the program is so good at producing appropriate responses that even Chinese speakers find it to be indistinguishable from a human Chinese speaker. In other words, the computer program passes the so-called Turing test, but does even it really understand Chinese?

The next step in Searle’s argument asks us to imagine a man completely innocent of the Chinese language in a closed room, perhaps sitting behind a large desk in it. He is supplied with an English language version of the same elaborate set of rules and protocols the computer program itself uses for correctly manipulating Chinese characters to answer questions put to it. Moreover, the man is directed to use these rules and protocols to respond to questions written in Chinese that are submitted to him through a mail slot in in the wall of the room. Someone outside the room would likely be quite impressed with the man’s responses to the questions posed to him and what seems to be the man’s understanding of Chinese. Yet all the man is doing is blindly following the same rules that govern the way the sequences of symbols in the questions should be responded to in order to yield answers. Clearly the man could process the Chinese questions and produce answers to them without any understanding any of the Chinese writing. Finally, Searle drops the mic by maintaining that both the man and the computer itself have no knowledge or understanding of Chinese. Read more »

by Mike Bendzela

[This will be a two-part essay.]

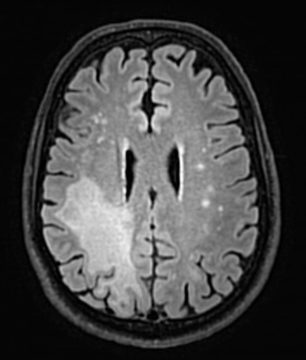

Ischemia

When the burly, bearded young man climbs into the bed with my husband, I scooch up in my plastic chair to get a better view. On a computer screen nearby, I swear I am seeing, in grainy black-and-white, a deep-sea creature, pulsing. There is a rhythmic barking sound, like an angry dog in the distance. With lights dimmed and curtains drawn in this mere alcove of a room, the effect is most unsettling. That barking sea creature would be Don’s cardiac muscle.

It is shocking to see him out of his work boots, dungarees, suspenders, and black vest, wearing instead a wraparound kitchen curtain for a garment. He remains logy and quiet while the young man holds a transducer against his chest and sounds the depths of his old heart, inspecting valves, ventricles, and vessels for signs of blood clots. This echocardiogram is part of the protocol, even though they are pretty sure the stroke has been caused by atherosclerosis in a cerebral artery.

The irony of someone like Don being held in such a room, amidst all this high-tech equipment, is staggering. He is a traditional cabinetmaker by trade and an enthusiast of 19th century technologies, especially plumbing systems and mechanical farm equipment. He embarked on a career as an Industrial Arts teacher in Maine in the 1970s but abandoned that gig during his student teaching days when he decided it was “mostly babysitting, not teaching.” The final break came when he discovered that one of his students could not even write his own name, and his superiors just said, “Move him along.”

In the dim quiet, while the technician probes Don’s chest, I mull over the conversation we just had with two male physicians. They had come into the room and introduced themselves as neurologists—Doctors Frick & Frack, for all I remember. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

McCormick’s Creek State Park is one of my favorite hiking spots. The creek flows through a little canyon with a waterfall in a beautiful wooded area. I’ve been visiting the park for more than 40 years. It’s a constant in my life, whether the waterfall is roaring in flood or slowed to a trickle during a dry spell or, once in a great while, frozen solid.

Late in the evening of Friday, March 31, an EF3 tornado struck the campground in the park. It caused considerable damage, and two people were killed. After the tornado left the park, it seriously damaged several homes in a rural area just outside Bloomington. It was part of an outbreak of 22 tornadoes throughout the state. A tornado that hit Sullivan, Indiana, destroyed or damaged homes and killed three people.

It was tough to see spring beginning with such serious damage and loss of life in a beloved spot. It was also sobering to see photographs of the destruction in Sullivan. It seems that I’ve seen many such images from places to the south and southwest of us this winter, and in fact 2023 has been an unusually active year for tornadoes in the U.S. so far. There have already been more tornado fatalities in 2023 than in all of 2022 nationwide. Read more »

by Rafiq Kathwari

“Please take the next flight to Nairobi,”

my niece said, her voice cracking over

WhatsApp. “Mom is in ICU. Lemme know

what time your flight lands. I’ll send the car.”

Early February morning on the Upper West Side,

I wore a parka, pashmina scarf, cap, gloves, rode

the A-Train to JFK, boarded Kenya Airways,

and 12 hours later

even before we landed at NBO, I peeled off my

layers anticipating equatorial warmth, the sun

at its peak, mid-afternoon. I waved at a tall, lean

man holding up RAFIKI scrawled on cardboard.

“Welcome,” he said.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Moses,” he said as we flew on the Expressway,

built by the Chinese.

“Oh,” I said. “My middle name is Mohammed.

Let’s look for Jesus and resurrect my sister.”

by David Greer

During the past decade, an environmental calamity has been gradually unfolding along the shores of North America’s Pacific coast. In what has been described as one of the largest recorded die-offs in history of a marine animal, the giant sunflower sea star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) has almost entirely disappeared from its range extending from Alaska’s Aleutian Islands to Baja California, its population of several billion having largely succumbed to a disease of undetermined cause but heightened and accelerated by a persistent marine heatwave of unprecedented intensity.

Equally tragic has been the collapse of kelp forests overwhelmed by the twin impact of elevated ocean temperatures close to shore and of the explosion of sea urchin populations, unchecked in their voracious grazing of kelp following the virtual extinction of their own primary predator, the sunflower sea star. One of the most productive ecological communities in the world, kelp forests act as nurseries for juvenile fish and other marine life in addition to sequestering carbon absorbed by the ocean. It took only a handful of years for most of the kelp to disappear, replaced by barren stretches of seabed densely carpeted by spiny sea urchins, themselves starving after reducing their main food supply to virtually nothing. When a keystone species abruptly vanishes from an ecosystem, the ripple effects can be far-reaching and catastrophic. Read more »

by Ali Minai

How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since OpenAI released the chatbot late in 2022. The simple answer to the question is, “No, it is not intelligent at all.” That is the answer that AI researchers, philosophers, linguists, and cognitive scientists have more or less reached a consensus on. Even ChatGPT itself will admit this if it is in the mood. However, it’s worth digging a little deeper into this issue – to look at the sense in which ChatGPT and other large language models (LLMs) are or are not intelligent, where they might lead, and what risks they might pose regardless of whether they are intelligent. In this article, I make two arguments. First, that, while LLMs like ChatGPT are not anywhere near achieving true intelligence, they represent significant progress towards it. And second, that, in spite of – or perhaps even because of – their lack of intelligence, LLMs pose very serious immediate and long-term risks. To understand these points, one must begin by considering what LLMs do, and how they do it.

How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since OpenAI released the chatbot late in 2022. The simple answer to the question is, “No, it is not intelligent at all.” That is the answer that AI researchers, philosophers, linguists, and cognitive scientists have more or less reached a consensus on. Even ChatGPT itself will admit this if it is in the mood. However, it’s worth digging a little deeper into this issue – to look at the sense in which ChatGPT and other large language models (LLMs) are or are not intelligent, where they might lead, and what risks they might pose regardless of whether they are intelligent. In this article, I make two arguments. First, that, while LLMs like ChatGPT are not anywhere near achieving true intelligence, they represent significant progress towards it. And second, that, in spite of – or perhaps even because of – their lack of intelligence, LLMs pose very serious immediate and long-term risks. To understand these points, one must begin by considering what LLMs do, and how they do it.

Not Your Typical Autocomplete

As their name implies, LLMs focus on language. In particular, given a prompt – or context – an LLM tries to generate a sequence of sensible continuations. For example, given the context “It was the best of times; it was the”, the system might generate “worst” as the next word, and then, with the updated context “It was the best of times; it was the worst”, it might generate the next word, “of” and then “times”. However, it could, in principle, have generated some other plausible continuation, such as “It was the best of times; it was the beginning of spring in the valley” (though, in practice, it rarely does because it knows Dickens too well). This process of generating continuation words one by one and feeding them back to generate the next one is called autoregression, and today’s LLMs are autoregressive text generators (in fact, LLMs generate partial words called tokens which are then combined into words, but that need not concern us here.) To us – familiar with the nature and complexity of language – this seems to be an absurdly unnatural way to produce linguistic expression. After all, real human discourse is messy and complicated, with ambiguous references, nested clauses, varied syntax, double meanings, etc. No human would concede that they generate their utterances sequentially, one word at a time. Read more »

by Fabio Tollon and Ann-Katrien Oimann

Getting a handle on the impacts of Large Language Models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 is difficult. These LLMs have raised a variety of ethical and regulatory concerns: problems of bias in the data set, privacy concerns for the data that is trawled in order to create and train the model in the first place, the resources used to train the models, etc. These are well-worn issues, and have been discussed at great length, both by critics of these models and by those who have been developing them.

What makes the task of figuring out the impacts of these systems even more difficult is the hype that surrounds them. It is often difficult to sort fact from fiction, and if we don’t have a good idea of what these systems can and can’t do, then it becomes almost impossible to figure out how to use them responsibly. Importantly, in order to craft proper legislation at both national and international levels we need to be clear about the future harm these systems might cause and ground these harms in the actual potential that these systems have.

In the last few days this discourse has taken an interesting turn. The Future of Life Institute (FLI) published an open letter (which has been signed by thousands of people, including eminent AI researchers) calling for a 6-month moratorium on “Giant AI Experiments”. Specifically, the letter calls for “all AI labs to immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4”. Quite the suggestion, given the rapid progress of these systems.

A few days after the FLI letter, another Open Letter was published, this time by researchers in Belgium (Nathalie A. Smuha, Mieke De Ketelaere, Mark Coeckelbergh, Pierre Dewitte and Yves Poullet). In the Belgian letter, the authors call for greater attention to the risk of emotional manipulation that chatbots, such as GPT-4, present (here they reference the tragic chatbot-incited suicide of a Belgian man). In the letter the authors outline some specific harms these systems bring about, advocate for more educational initiatives (including awareness campaigns to better inform people of the risks), a broader public debate, and urgent stronger legislative actions. Read more »

“Once upon a time, I, Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu), dreamt I was a butterfly, fluttering hither and thither, to all intents and purposes a butterfly. I was conscious only of my happiness as a butterfly, unaware that I was Zhuangzi. Soon I awakened, and there I was, veritably myself again. Now I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man. Between a man and a butterfly there is necessarily a distinction. The transition is called the transformation of material things.” —Chinese poet/philosopher, 4th century BC

Chuang Tzu’s Butterfly

the other night when I was sleeping

gone so far the moonlight leaping

through my window, past the curtain,

instantly I knew for certain

that I was a butterfly

I went flitting flower to flower,

I grew freer by the hour,

no concern for job or romance,

through the night I just

danced and I danced

but when the morning light was breaking,

the sun, the sun, the moon forsaken,

I got up threw back the covers,

instantly I was another

knew I was a man again

between that butterfly and me

I must make some kind of line,

can’t have a common destiny

between me and this lungful of air that I breathe

I must make some kind of line

something solid my reason can squeeze

Jim Culleny

(Written as a song in 1975)

by Thomas R. Wells

Environmentalists are always complaining that governments are obsessed with GDP and economic growth, and that this is a bad thing because economic growth is bad for the environment. They are partly right but mostly wrong. First, while governments talk about GDP a lot, that does not mean that they actually prioritise economic growth. Second, properly understood economic growth is a great and wonderful thing that we should want more of.

Environmentalists are always complaining that governments are obsessed with GDP and economic growth, and that this is a bad thing because economic growth is bad for the environment. They are partly right but mostly wrong. First, while governments talk about GDP a lot, that does not mean that they actually prioritise economic growth. Second, properly understood economic growth is a great and wonderful thing that we should want more of.

Governments around the world – of every ideology – are in favour of economic growth all else being equal. Economic growth increases the wealth of a population and hence improves their options and those of the government that rules them. This is extremely politically convenient as it allows governments to serve all their various constituencies without having to make hard choices between them, and so keep them happy enough that they get to stay in power. Honest politicians can provide more public services to those who demand them, while keeping the tax rate the same. Corrupt politicians can get away with funneling money to themselves and their cronies without risking revolution. More money means fewer and easier political problems.

However, just because someone values a certain outcome, does not mean that they value it enough to take the necessary painful steps to achieve it. (Or else everyone would get A’s in all their exams and keep the waist size they had in high-school.) It turns out that the policies governments need to implement (or stop implementing) in order for their societies to get richer are often more politically costly than they are worth. Take for example governments’ responsibility for the housing crisis across the rich world, in which the price of housing rises faster than incomes. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 1, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 1, 2023.

Digital photograph.

by Ada Bronowski

There is something bewildering about life in Paris under Nazi occupation: theatres, cinemas, cabarets and cafés in full swing, swarming with Nazi officials mingling with the locals, when, all the while, people are arrested in broad daylight, dragged out of their apartments, tracked, tortured and killed for being Jewish or communist, active in the resistance, gay or just for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. In the midst of food shortages and curfews, the champagne galas, dinners at Maxim’s, lobster at the Etoile de Kleber, the thirst for entertainment and the possibilities for quenching it multiplied. A newly published French book by the writer, producer and playwright Pierre Laville, La Guerre Les Avait Jetés Là (literally translated: The war threw them there, Robert Laffont, 2023), delves with compassion and understanding into the ambiguities of living in Nazi-invaded Paris focusing on the ins and outs of one of the most important theatrical institutions in France, the Comédie-Française. Read more »

by Rebecca Baumgartner

A Conversation

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” –Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, 1791

“Many others … say that it is dangerous and absurd to base modern public safety on the 1700s and 1800s when a gun can be built with a 3-D printer and plans shared on the internet.” – Shawn Hubler, The New York Times, March 16, 2023

“The Republicans have turned the Second Amendment into a Golem. They’ve animated it, weaponized it, and unleashed it upon their enemies. It is killing children. It is time to hit this monstrosity in its clay feet.” –Elie Mystal, The Nation, August 7, 2019

“We only receive what we demand, and if we want hell, then hell’s what we’ll have.” –Jack Johnson, “Cookie Jar”

“Not doing anything about this is an insane dereliction of our collective humanity.” –Stephen Colbert

“_________________________________” –The 3,263 American children killed by guns since 2014 (as of March 30, 2023)

Two Axioms

These are not political stances. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Joseph Shieber

One of the strange juxtapositions appearing in the past few weeks was the publication of Ibram X. Kendi’s essay, “The Crisis of the Intellectuals” in The Atlantic, followed – a day or so later – by Marty Baron’s essay, “We want objective judges and doctors. Why not journalists too?” in the Washington Post.

Kendi’s essay is focused on pushing back against the traditional framing of the intellectual “as measured, objective, ideologically neutral, and apolitical” – a framing that Kendi finds crippling and, indeed, life-destroying. In contrast, Baron’s essay is focused on defending the ideal of objectivity from its detractors – including, although he is not mentioned by name, Kendi.

The authors themselves also offer a marked contrast. Although now undoubtedly an academic superstar and public intellectual, Kendi himself describes his ascension as unlikely, given that he “came from a non-elite academic pedigree, emerged proudly from a historically Black university, [and] earned a doctorate in African American Studies.” In contrast, Baron enjoyed a more predictable pathway to the pinnacle of his profession. He earned his B.A. and M.B.A. degrees in four years from Lehigh University, began his journalistic career at the Miami Herald, and then progressed quickly from the Los Angeles Times to the New York Times, and then – now as executive editor – back to the Herald, after which he became executive editor of the Boston Globe (immortalized in the movie Spotlight), and finally the executive editor of the Washington Post. Kendi is 40; Baron, a generation older, is 68. Read more »

by Jochen Szangolies

The simulation argument, most notably associated with the philosopher Nick Bostrom, asserts that given reasonable premises, the world we see around us is very likely not, in fact, the real world, but a simulation run on unfathomably powerful supercomputers. In a nutshell, the argument is that if humanity lives long enough to acquire the powers to perform such simulations, and if there is any interest in doing so at all—both reasonably plausible, given the fact that we’re in effect doing such simulations on the small scale millions of times per day—then the simulated realities greatly outnumber the ‘real’ realities (of which there is only one, barring multiversal shenanigans), and hence, every sentient being should expect their word to be simulated rather than real with overwhelming likelihood.

On the face of it, this idea seems like so many skeptical hypotheses, from Cartesian demons to brains in vats. But these claims occupy a kind of epistemic no man’s land: there may be no way to disprove them, but there is also no particular reason to believe them. One can thus quite rationally remain indifferent regarding them.

But Bostrom’s claim has teeth: if the reasoning is sound, then in fact, we do have compelling reasons to believe it to be true; hence, we ought to either accept it, or find flaw with it. Luckily, I believe that there is indeed good reason to reject the argument. Read more »